Difference between revisions of "General Conference Mennonite Church (GCM)"

| [checked revision] | [checked revision] |

m |

m (Text replace - "Ohio (State)" to "Ohio (USA)") |

||

| Line 65: | Line 65: | ||

In 1852 Oberholtzer began publishing <em>[[Religiöser Botschafter, Der (Periodical)|Der Religiöser Botschafter]], </em>the first continuing Mennonite periodical in North America. In 1858 the new conference adopted a resolution strongly favoring mission work. European Mennonite contacts were renewed. Ministers were appointed to visit congregations in the interest of spiritual growth. In 1866 a mission society was established and city mission work begun. Oberholtzer served as chairman of this conference from 1847 to 1872 practically without a break. | In 1852 Oberholtzer began publishing <em>[[Religiöser Botschafter, Der (Periodical)|Der Religiöser Botschafter]], </em>the first continuing Mennonite periodical in North America. In 1858 the new conference adopted a resolution strongly favoring mission work. European Mennonite contacts were renewed. Ministers were appointed to visit congregations in the interest of spiritual growth. In 1866 a mission society was established and city mission work begun. Oberholtzer served as chairman of this conference from 1847 to 1872 practically without a break. | ||

| − | Two unfortunate minor schisms occurred within the first ten years of the new group's history. The first was the breaking away of a small group in 1851 led by Abraham and Henry Hunsicker, bishop and preacher respectively, who, excommunicated by the new conference, continued for a time a small group known as the [[Trinity Christian Society (Collegeville, Pennsylvania, USA)|Trinity Christian Society]], which ultimately disappeared. The second schism was that led by [[Gehman, William (1827-1918)|William Gehman]] in 1857 as a result of the prohibition of prayer meetings by the new conference, followed by the excommunication by the conference of Gehman and 23 others. This group, first called the [[Evangelical Mennonite Society|Evangelical Menonites]], later merged with other similar groups in [[Ontario (Canada)|Ontario]], [[Ohio ( | + | Two unfortunate minor schisms occurred within the first ten years of the new group's history. The first was the breaking away of a small group in 1851 led by Abraham and Henry Hunsicker, bishop and preacher respectively, who, excommunicated by the new conference, continued for a time a small group known as the [[Trinity Christian Society (Collegeville, Pennsylvania, USA)|Trinity Christian Society]], which ultimately disappeared. The second schism was that led by [[Gehman, William (1827-1918)|William Gehman]] in 1857 as a result of the prohibition of prayer meetings by the new conference, followed by the excommunication by the conference of Gehman and 23 others. This group, first called the [[Evangelical Mennonite Society|Evangelical Menonites]], later merged with other similar groups in [[Ontario (Canada)|Ontario]], [[Ohio (USA)|Ohio]], and [[Indiana (USA)|Indiana]] to form the [[Mennonite Brethren in Christ|Mennonite Brethren in Christ]]. |

A second center of new life developed among the Mennonites who had migrated from [[Pennsylvania (USA)|Pennsylvania]] to Ontario for economic reasons, but also to keep their promise of allegiance to the English Crown. Here [[Hoch, Daniel (1805-1878)|Daniel Hoch]] of Vineland in Lincoln County was leader. Because of aggressive itinerant evangelistic work, he with other leaders was excommunicated by the [[Mennonite Conference of Ontario and Quebec|Ontario Mennonite Conference]] in 1849. Long before this, Mennonites had also settled in Ohio, where [[Hunsberger, Ephraim (1814-1904)|Ephraim Hunsberger]], who also knew Hoch, became the leader. In 1855 "The [[Ohio and Canada West Mennonite Conference|Conference Council of the United Mennonite Community of Canada-West and Ohio]]" was formed, a very small group with three small congregations, with Hoch and Hunsberger as leaders. Here, too, the cause of missions was urged. In 1858 this Canada-Ohio Conference met at [[Wadsworth (Ohio, USA)|Wadsworth]], Ohio, to which the [[Pennsylvania (USA)|Pennsylvania]] group was also invited. The following year this conference created a "Home and Foreign Missionary Society of Mennonites." Unfortunately Hoch later withdrew from the group to join the Mennonite Brethren in Christ, and the Ontario parts of the conference disappeared. | A second center of new life developed among the Mennonites who had migrated from [[Pennsylvania (USA)|Pennsylvania]] to Ontario for economic reasons, but also to keep their promise of allegiance to the English Crown. Here [[Hoch, Daniel (1805-1878)|Daniel Hoch]] of Vineland in Lincoln County was leader. Because of aggressive itinerant evangelistic work, he with other leaders was excommunicated by the [[Mennonite Conference of Ontario and Quebec|Ontario Mennonite Conference]] in 1849. Long before this, Mennonites had also settled in Ohio, where [[Hunsberger, Ephraim (1814-1904)|Ephraim Hunsberger]], who also knew Hoch, became the leader. In 1855 "The [[Ohio and Canada West Mennonite Conference|Conference Council of the United Mennonite Community of Canada-West and Ohio]]" was formed, a very small group with three small congregations, with Hoch and Hunsberger as leaders. Here, too, the cause of missions was urged. In 1858 this Canada-Ohio Conference met at [[Wadsworth (Ohio, USA)|Wadsworth]], Ohio, to which the [[Pennsylvania (USA)|Pennsylvania]] group was also invited. The following year this conference created a "Home and Foreign Missionary Society of Mennonites." Unfortunately Hoch later withdrew from the group to join the Mennonite Brethren in Christ, and the Ontario parts of the conference disappeared. | ||

Revision as of 03:30, 20 February 2014

1990 Article

Introduction

Elements of both continuity and discontinuity are evident in developments within the General Conference Mennonite Church since 1950. Alongside the Mennonite Church (MC) and the Mennonite Brethren, it is one of the three main Mennonite groups in North America. The constitutional revision in 1950, which saw the restructuring of the several boards, including administrative separations between home and foreign missions agencies, was itself revised in 1968. At that time the nomenclature was changed from boards to commissions, except for the General Board. A further basic change was that of representation. Whereas earlier all board members were elected by the general conference, after 1968 each regional or district conference in the United States and the Women in Mission placed one representative on each of the commissions and on the seminary board of trustees. The Conference of Mennonites in Canada placed two members on each.

The 1968 constitution delineated a change in the relationship to the South American churches. These congregations subsequently established their primary relationships among themselves as regional or national conferences. Their tie to the General Conference became a fraternal one, fostered through the Commission on Overseas Mission. During the last two decades there has been a gradual move to separate some of the issues into their national contexts. Canadian members thought it improper for the binational general conference to be dealing with issues that had to do primarily with the United States congregations. The result was the establishment of the US Assembly, a US Council and Commission on Home Ministries (US), 1981-83.

Growth

Growth of the General Conference Mennonite Church has continued at a slow pace, not for lack of focus on evangelism, but for a lack of practical handles to bring people into the doors of the church. Periodically the conference has adopted statements on evangelism with each conference session setting forth certain evangelistic and church growth goals. Thus the Commission on Home Ministries in 1983 presented its proposals for outreach, including one for the preparation of 300 church planters, and another for enriching evangelism with peace and justice witness, and expression of a strong desire to keep evangelism and the practical Christian life linked together.

In 1997 the total number of congregations in the General Conference Mennonite Church stood at 521, with 67,353 members. This was an increase of 251 and 47,187 respectively from 1950. The most rapid growth has come in Canada. In the United States the increase in membership has been from 31,687 in 1950 to 35,333 in 1997. In Canada the increase has been from 15,500 in 1950 to 32,020 in 1997.

Commissions

As of 1998 the overall program of the conference continued to be carried by the program commissions, the seminary, and several other agencies.

The Commission on Home Ministries, charged with ministry on the home front, has helped support church planting ventures among Hispanic, Mexican, Chinese, Laotian, Creole, Native or Indian, and Vietnamese peoples. It has sought to promote ministry to the poor and to law offenders, aid to refugees, peace education and peace activism (including assistance for draft-age youth), awareness of the danger of nuclear weapons, aid to vocational shifts, ministry to the aged, and awareness of social changes and of possible Christian witness in response to such change. At the 1986 triennial conference plans were presented to move more aggressively into ministry to ethnic and language minorities, in part because of the changed pattern of immigrants coming to the United States and Canada.

The mission thrust overseas, carried by the Commission on Overseas Ministries, has seen both major expansions and radical adjustments. In the 1950s work was begun in Japan (1950) and Taiwan (1953). In both India and Zaire, where General Conference mission work had been underway much longer, the process of turning over the work to Indians and Zairians was underway in the 1950s. In India this brought about considerable ferment. Attempts were made to develop a more peaceful partnership in the 1960s; the 1970s then culminated in the dismantling of the mission organization after some disturbing relationships. In Zaire, on the other hand, the political upheaval in the 1960s led to an accelerated move towards the independence of the Zairian church. This was sparked first by what James Juhnke calls "organizing disintegration," followed by a split in the national church along tribal lines. Although the political scene did gradually stabilize, this was followed by severe economic deterioration. The Zaire Mennonite Church, nonetheless, matured in its independence, and then in turn invited the General Conference to send missionaries back as fraternal workers.

In the context of such changes the Commission on Overseas Ministries held a "Goals, Priorities and Strategies Conference" in 1972. Its purpose was to articulate for the commission its stated intent for the second century of witness, and to establish priorities for its task. The top five priorities were evangelism and church planting, leadership training, transfer of the mission work to national leadership, the strengthening of Anabaptist-Mennonite emphasis on discipleship, love, peace, nonresistance, and unity; and economic development.

The Commission on Education (COE) continued its focus on preparing material to help the church in its educational task. Working with Faith and Life Press in partnership with Bethel College, it prepared Sunday school literature and teaching aids and sponsored the publication of books and pamphlets, e.g. the Mennonite Historical Series. Jointly with the Congregational Literature Division of Mennonite Publishing House (MC), it prepared and published the Foundation Series (for children), the Adult Bible Study Guide for the International Uniform Lessons series, the periodical Rejoice, and, with other groups, published the Foundation Series for Adults. These joint ventures have resulted in some of the best teaching materials available for the local church.

Denominational periodicals have continued to be published. Der Bote (The Messenger), published weekly in Winnipeg, has continued to be a family paper bringing German-speaking Mennonites around the world into dialogue with one another. The number of subscribers continues to drop as the younger generations in Canada and the United States use less and less German. The Mennonite, published biweekly, celebrated its centennial in 1985; that same year it commemorated the 125th anniversary of the founding of the General Conference Mennonite Church with a special issue. In February, 1998 The Mennonite merged with the (Old) Mennonite Church (MC) publication, Gospel Herald, to form a new integrated U.S. Mennonite weekly publication, also called The Mennonite.

Youth work has continued as another of the portfolios of the COE. S.F. Pannabecker wrote that by 1950 the youth work might be said to have come of age. Young people participated energetically in the work of the church with a program that particularly emphasized faith, fellowship, and service. During the 1960s the focus shifted from overall conference planning to getting the local groups involved in their communities and districts. The result was the disbanding of the Young People's Union in 1969, with most of the regional conferences fostering strong youth programs. Annual statistical surveys by the COE have made it possible to remain in touch with youth studying at non-Mennonite institutions. A Student Services Committee was instituted in 1959 to minister to campus groups. Arena, a joint Mennonite graduate student periodical, was begun in 1967, and With, a periodical for younger students, saw a wide circulation. Arena changed to Forum in 1970, and was discontinued in 1981, due in part to the controversial topics which were being discussed.

Theological Education

Mennonite Biblical Seminary, the theological training institution for the General Conference, was moved from Chicago, where it was associated with Bethany Theological Seminary (Church of the Brethren) for 13 years, to Elkhart, Ind. in 1958. It entered into an association with Goshen College Biblical Seminary (MC) to form the Associated Mennonite Biblical Seminaries (1958). Initially, classes were taught on campuses at Goshen and Elkhart. The move to one campus at Elkhart was made in 1969. In 1994 the two seminaries were incorporated together as the Associated Mennonite Biblical Seminary; enrollment in 1995 was 169. As of 1998, four degrees were offered: the Master of Divinity, the Master of Arts in Peace Studies, the Master of Arts in Theological Studies, and the Certificate in Theology.

Ministerial training has been expanded to conference-based centers in eastern Pennsylvania, Virginia, Kansas and Ontario. In these centers courses have been offered to pastors and laypersons, affording them training while on the job. The Committee on the Ministry was also charged with helping to determine and to plan for the type of pastoral training called for in the next decades. In Canada the Bible schools which have served a very strategic role in biblical training have fallen on hard times, and few continue to function. On the other hand, Canadian Mennonite Bible College, operated by the Conference of Mennonites in Canada in Winnipeg, has continued as a strong training school for church workers.

Auxiliaries

The Women's Missionary Association, which was organized in 1917, became Women in Mission in 1974, and integrated with the Women's Missionary and Service Commission of the Mennonite Church (MC) in 1997 to become Mennonite Women. Focusing on study and service, the group has drawn members from churches throughout North America and has supported various local, regional, and national projects. In 1998 it provided financial assistance to each of the commissions as well as the seminary, preparing mission education materials, offering scholarships to women students, assisting Hispanic and overseas women in leadership training, sponsoring reciprocal cross-cultural visits with women overseas, aiding women in developing and sharing their gifts, strengthening family relationships, and fostering spiritual growth.

Organized in 1945, Mennonite Men initially had two purposes: to assist financially with special projects and to help organize district Mennonite Men's groups for fellowship and service. After a decline during the 1970s, a new vitality has been born with the decision to assist financially in the establishment of new churches. The group's project in the latter half of the 1980s, the Tenth Man program, solicited members to contribute annually for church planting.

Study Conferences

The General Conference emphasized an appropriate expression of the Christian faith. For some, verbal expression has been very important; for others, practical life receives the focus.

The doctrinal statements entitled Vision: Healing and Hope and Confession of Faith in a Mennonite Perspective were jointly adopted by the Mennonite Church (MC) and the General Conference Mennonite Church (GCM) in 1995. Other doctrinal statements based on Scriptural teaching have been formulated on many different, specific theological, ecclesiastical, and ethical issues. The study conferences which have convened periodically since the 1950s have been unique. These have dealt with such issues as the Church, the Gospel and War (1953), the Believers Church (1955), Evangelism (1958), Christian Unity in Faith and Witness (1960), and Church and Society (1961). These study conferences, together with a number of study commissions and various resolutions at triennial sessions, resulted in official statements, accepted by the conference, on the Believers' Church, the Christian and Race, the Christian and Nuclear Power, Capital Punishment, Inter-Mennonite Cooperation and Unity, Simultaneous Evangelism, Proclamation of the Gospel, Nationalism, Poverty and Hunger, Church Renewal, Authority of the Scriptures, Christian Stewardship of Energy Resources, Offender Ministries, Divorce and Remarriage, Abortion, and Human Sexuality.

Periodically, congregations have left the General Conference. Robert Kreider, speaking at the triennial session in 1971, stated: "We undoubtedly are a more frankly divided Conference than in 1953, [as is illustrated by] the Fundamentalist-non-Fundamentalist gulf, the generation gap, the peace-patriotism conflict, the distrust of institutions and structures, the new nationalism that separates the United States and Canada, the young churches overseas assertive of their new freedom." (Where Are We Going?, 21) To help facilitate dialogue between those of differing viewpoints, and to speak specifically to the question of Biblical interpretation, two special conferences termed "Dialogue on Faith" were convened in the 1980s. Those who attended listened to each other and discovered an integrity which enabled them to accept each other as brothers and sisters in Christ despite their differences.

The distinctive features and characteristics of the General Conference Mennonite Church have been: readiness to cooperate in many inter-Mennonite activities, congregational independence, diversity of thought and life-style, a free borrowing from outside Mennonite tradition, laxness in applying Christian discipline, a strong desire to remain biblical while recognizing that differences in hermeneutical approach to the Bible lead to differing interpretations of the Scriptures, a rediscovery and emphasis of a peace position, a constant attempt to keep evangelism and Christian education and nurture together, and a continued emphasis on church renewal. This renewal was given expression at the 1986 triennial session which adopted a Call to Kingdom Commitments as a development plan, calling for commitments of prayer, time and service, and financial support. Four major goals were reaffirmed: to evangelize, teach and practice biblical principles, train and develop church leaders, and achieve Christian unity.

The 1980s and 1990s also saw a gradual movement toward integration of the two largest North American Mennonite bodies. The two Mennonite Church (MC) conferences in Ontario, together with the Conference of United Mennonite Churches of Ontario (GCM), formed the Mennonite Conference of Eastern Canada in 1988. The General Assembly of the Mennonite Church (MC) met jointly with the triennial session of the General Conference Mennonite Church in Bethlehem, Pa. in 1983; a second joint meeting occurred in Normal, Ill. in 1988. Numerous local congregations are affiliated with both MC and GCM bodies. At the 1995 joint sessions of the MC and GCM in Wichita, Kansas, the two conferences voted in favour of a formal merger, setting 1999 as their target date for complete denominational integration. In 1999 at joint sessions of the Mennonite Church, General Conference Mennonite Church and Conference of Mennonites in Canada, the formation of two national conferences from the three bodies was approved -- Mennonite Church USA and Mennonite Church Canada. The formal end of the General Conference Mennonite Church took place 31 January 2002. Integration was also taking place on the regional conference level, as evidenced by the creation of the dually-affiliated Pacific Northwest and Pacific Southwest Conferences from the former Pacific Coast Conference (MC), Southwest Conference (MC), and Pacific District Conference (GCM). -- Henry Poettcker

1956 Article

Introduction

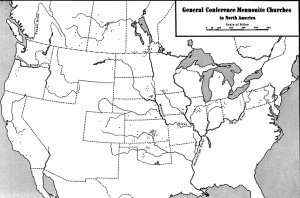

The General Conference Mennonite Church (formerly the General Conference of the Mennonite Church of North America) was the first American Mennonite general conference organization and in 1955 the second largest Mennonite body of America, was organized 28 May 1860 at West Point, Iowa, by three small Mennonite congregations. By 1955 it had grown to 244 congregations with a membership exceeding 50,000, located in the United States, Canada, and South America.

Background

The first period of Mennonite history in America roughly coincides with the colonial period. This was a time of immigration, beginnings, and setting of patterns. Although there was great appreciation of the freedom in the new country, there was also a deep consciousness of separation from the surrounding world, due to difference in religious convictions and practices, and to some extent in language and customs. Outside pressure, especially as expressed by aggressive Scottish-Irish neighbors, urging political participation, and military service as they faced the Revolutionary War, caused much concern among Mennonites.

After the Revolution (1789) to about the middle of the 19th century the continued lack of Old World contacts and increasing isolation in America gradually tended to congeal the patterns of life and thought among the American Mennonites. During this second period of American Mennonite history, with largely older and untrained leadership, patterns of custom and tradition became increasingly set and authoritative. Slowly blood relationship, the family ideal of religion, a cultural church, separation on a social as well as religious basis, tended to crowd out the personal, voluntary, glowing spiritual life of the "new creature in Christ" which had been so real and vital in earlier days.

John C. Wenger wrote as follows of these early Mennonite days in America: "Their Christianity was not that of 'radical' Christians; it had settled down to a comfortable, conventional, denominational type. There was no thought of evangelistic work, no need for any kind of mission work, no occasion to alter any of the set patterns of worship. The faith and practice of the immigrants was good and satisfying; why change? From 1683 to the ordination of John H. Oberholtzer, almost 160 years later, no significant changes were made, and no one intended to make any. The Bible had not changed; why should anyone introduce any innovations? Only with great effort would it be possible to introduce Sunday schools, evangelistic services, Bible study and prayer meetings, evening services, and church boards of charities, publication, education, and missions. This was the situation 160 years after the thirty-five Krefelders arrived at Philadelphia on the good ship Concord, October 6, 1683."

About the new life under these conditions H. P. Krehbiel wrote as follows: "During that period a number of persons being spiritually awakened, recognized the lethargic condition of the church and endeavored, though not wisely, to awaken the church from its drowsy spiritual stupor. Unfortunately the effect was schismatic . . . . Yet there was hope in the stir and commotion."

John H. Oberholtzer, a young school-teacher and minister who later also became a businessman (locksmith) and publisher, was the leader of a more progressive group in Pennsylvania. After he and 15 other ministers were excommunicated by the older group for insisting on a written constitution. they organized the "East Pennsylvania Conference of the Mennonite Church" (eventually becoming the Eastern District Conference of the General Conference) on 28 October 1847. Besides the adoption of a written constitution they advocated dropping the collarless ministerial coat, keeping minutes of meetings, publishing a catechism, Sunday-school work, free association with other denominations, mission work, etc.

In 1852 Oberholtzer began publishing Der Religiöser Botschafter, the first continuing Mennonite periodical in North America. In 1858 the new conference adopted a resolution strongly favoring mission work. European Mennonite contacts were renewed. Ministers were appointed to visit congregations in the interest of spiritual growth. In 1866 a mission society was established and city mission work begun. Oberholtzer served as chairman of this conference from 1847 to 1872 practically without a break.

Two unfortunate minor schisms occurred within the first ten years of the new group's history. The first was the breaking away of a small group in 1851 led by Abraham and Henry Hunsicker, bishop and preacher respectively, who, excommunicated by the new conference, continued for a time a small group known as the Trinity Christian Society, which ultimately disappeared. The second schism was that led by William Gehman in 1857 as a result of the prohibition of prayer meetings by the new conference, followed by the excommunication by the conference of Gehman and 23 others. This group, first called the Evangelical Menonites, later merged with other similar groups in Ontario, Ohio, and Indiana to form the Mennonite Brethren in Christ.

A second center of new life developed among the Mennonites who had migrated from Pennsylvania to Ontario for economic reasons, but also to keep their promise of allegiance to the English Crown. Here Daniel Hoch of Vineland in Lincoln County was leader. Because of aggressive itinerant evangelistic work, he with other leaders was excommunicated by the Ontario Mennonite Conference in 1849. Long before this, Mennonites had also settled in Ohio, where Ephraim Hunsberger, who also knew Hoch, became the leader. In 1855 "The Conference Council of the United Mennonite Community of Canada-West and Ohio" was formed, a very small group with three small congregations, with Hoch and Hunsberger as leaders. Here, too, the cause of missions was urged. In 1858 this Canada-Ohio Conference met at Wadsworth, Ohio, to which the Pennsylvania group was also invited. The following year this conference created a "Home and Foreign Missionary Society of Mennonites." Unfortunately Hoch later withdrew from the group to join the Mennonite Brethren in Christ, and the Ontario parts of the conference disappeared.

About the middle of the 19th century several groups of Mennonites from Bavaria and the Palatinate emigrated to America, most of them settling in Illinois and Iowa. They were acquainted with mission and publication work and were otherwise rather progressive. Soon contact was made with the Oberholtzer group in Pennsylvania, the Hoch group in Canada. and the Hunsberger group in Ohio. Daniel Krehbiel was the leader of the Iowa-Illinois group, which at that time was unaffiliated.

Organization, Growth, and Activities

The various Mennonite groups interested in union were invited to send representatives to a conference which was to meet 28 May 1860, at West Point, Lee County, Iowa. At this meeting, with three congregations participating, Oberholtzer was elected chairman, and Christian Schowalter, a teacher in the Iowa community, secretary. A committee of five was elected to work out a "Plan of Union" and report the next day. This the committee did. The conference, after some discussion, adopted the plan, and "The General Conference of the Mennonite Church of North America" was under way. The second meeting was held at Wadsworth, Ohio, 20-23 May 1861, with eight congregations responding. Gradually the movement grew. Later most of the 19th-century immigrants from Russia, Prussia, Poland, and Switzerland, joined the Conference. In 1953 the Central Conference Mennonites came in as a district conference, merging with the Middle District Conference in 1956. At General Conference sessions individual congregations have been coming in. The name was changed in 1953 to "General Conference Mennonite Church."

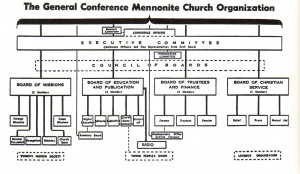

The organization in place in 1955 provided that each congregation had direct relation to the General Conference. At the triennial meeting of the Conference each congregation had one vote for every 30 members or fraction thereof. The accompanying chart indicates that organization and areas of activity.

In the interest of democracy, no person could succeed himself more than once in any office, committee, or board; with certain exceptions no person could hold a position in more than one standing board or conference office at one time. The conference officers, plus two representatives from each of the four standing boards, formed the executive committee which acted for the conference between sessions. The Council of Boards and standing committee met conjointly once a year (usually in December) for consideration of common problems.

There were six district conferences within the General Conference: Eastern, Middle-Central, Northern, Western, Pacific, and Canadian. The congregations had a direct relationship to their respective district conferences. However, the district conferences had no direct organizational connection with the General Conference. Each congregation, as well as each district conference, was more or less autonomous. The General Conference assumed only an advisory, not a legislative, relationship to the congregations and the district conferences. From the very beginning the emphasis had been on "unity in essentials; liberty in nonessentials; and love in all things." However, the boards were directly responsible to the General Conference, and were not autonomous.

The Great Commission of our Lord was from the beginning considered the basic task of the Conference and the congregations belonging to it. The first American Mennonite mission work was established by the General Conference in 1880. The missionary was S. S. Haury of Summerfield, Illinois, and the field was among the American Indians in Oklahoma. In time (1900 and later) foreign mission work was begun in India, China, South America, Africa, Japan, and Taiwan. Even before the foreign work was begun, home mission work was done, mainly with the thought of gathering together scattered Mennonite families. Altogether, some 250 missionaries had been sent to foreign lands and some 200 persons had been employed as home mission workers by the 1950s.

Publication and education were emphasized from the beginning. During the years some twenty-five different publications came into being by the 1950s, only about one half of which were still in existence. The Mennonite and Der Bote were the official English and German Conference papers. Sunday-school and young people's material, church hymnals, and a variety of other Christian material was produced. Three bookstores were operated by the Conference (Newton, KS; Berne, IN; Rosthern, Saskatchewan, Canada). The following schools were serving the Conference constituency and reported to its triennial sessions: Mennonite Biblical Seminary in Chicago (which was under a board elected by the General Conference); Bethel College in North Newton, Kansas; Bluffton College in Bluffton, Ohio; Freeman Junior College in Freeman, South Dakota; Rosthern Junior College in Rosthern, Saskatchewan; Mennonite Collegiate Institute, Gretna, Manitoba; and Canadian Mennonite Bible College in Winnipeg. In addition to these there were a number of academies and Bible schools. Approximately one thousand General Conference young people annually attended the above conference-related schools.

A third area of activity pertained to relief and peace. Besides carrying on its own program in these areas, the Conference helped to organize the Mennonite Central Committee in 1920 and ever since has been affiliated with it in work of general relief, Civilian Public Service, colonization, peace education, etc. Hospitals and homes for the aged were maintained in various areas by district conferences or local groups. The Mennonite nonresistant faith found positive expression in relief work and voluntary service.

Cultural Background

All American Mennonites of the 1950s were either of Swiss-South German or Dutch-North German background. There was no other Mennonite conference that had such a variety of groups with different cultural backgrounds as the General Conference, which was composed of many shades of these two main cultural groups. We mention briefly a few facts concerning each.

Swiss-South German Background

- The descendants of those who came out of the Mennonite Church (MC) with Pennsylvania-German background in the 1950s largely constituted the membership of 28 congregations, mostly in Eastern Pennsylvania.

- The descendants of those who came to America from South Germany in the 19th century constituted most of the membership of 12 congregations. This group earlier exerted great influence in directing the organization and development of the General Conference. The congregations at Donnellson, Iowa; Summerfield, Illinois; Halstead and Moundridge, Kansas; Reedley and Upland, California, were some of those belonging to this group.

- The descendants of those who came directly from Switzerland to Ohio and Indiana in the 19th century in the 1950s constituted the major part of the membership of 11 congregations, e.g., Berne, Indiana, and Bluffton, Ohio.

- The descendants of the Swiss who came from South Germany and France, via Volhynia, Russia, arriving in 1874, constituted the major part of the membership of 12 congregations. The Eden Church at Moundridge, Kansas, belongs here; also the congregations at Freeman, SD; Pretty Prairie, Kansas, and others.

- The descendants of the Swiss who came from South Germany via Galicia largely constituted the membership of 5 congregations located at Arlington, Kansas; Butterfield, Minnesota, and elsewhere.

- The descendants of Amish background largely constituted the membership of 27 congregations mostly in the Central District Conference, largely in Illinois and Indiana, formerly (before 1872) affiliated with the Amish Mennonite (MC) group.

- The descendants of Hutterite background now largely constitute the membership of 7 congregations, mostly in South Dakota.

Dutch-North German Background

- The descendants of the Dutch who came via Prussia in 1874 in 1955 largely constituted the membership of 6 congregations. Among them there are churches at Beatrice, Nebraska, and Newton and Whitewater, Kansas.

- The descendants of the Dutch who came via Prussia and South Russia, arriving in America in 1874 ff., constituted the major part of 70 congregations. This was the largest cultural group in the General Conference. The congregations were scattered all over the West. Many were located in Kansas, Minnesota, and Canada. Alexanderwohl at Goessel, and Hoffnungsau at Inman, Kansas, were two of the original settlements in the United States, from which came a number of younger congregations. In Canada the large Bergthal congregation in Manitoba and the Rosenort congregation in Saskatchewan belonged to this group.

- The descendants of the Dutch who came via Prussia and Polish Russia in 1874 now largely constituted the membership of 11 congregations. Among them were Gnadenberg at Elbing, Johannesthal at Hillsboro, and churches at Canton and Pawnee Rock, Kansas, and Meno, Oklahoma.

- The descendants of the Dutch who came via Prussia and South Russia, arriving after World War I (1922-1925, 1930, and 1948-1953), largely constituted the membership of 40 congregations, practically all in Canada.

Mixed Background

More than a dozen congregations already had such a mixture of members of various Mennonite backgrounds as well as some of non-Mennonite background that it was impossible to classify them. The Bethel College congregation at North Newton, Kansas is an example of this. Many congregations, through individual family migrations, were becoming more and more mixed.

In the past the various General Conference Mennonite groups lived in different countries, separated from each other for many decades at a time; thus each developed its own peculiarities, not only in dress and food, but also in point of view and world outlook, in language and social customs, as well as in Biblical interpretation and religious practice. However, in essentials they were one; and because of their feeling of kinship and the desire to work with each other, they were drawn together since coming to America and have been influenced by the social process involved.

Characteristics of General Conference Mennonites

Renewed attention was given in the mid-20th century to the nature and function of the church. It was spoken of as an outpost —a mission station—in the world to win the lost to Christ. Increasingly the church was thought of as the very body of Christ in a given community, and as the visible reality of our Lord in the world. As His body the local congregation, as well as the over-all organization, was to serve as His hands and feet, and with His mind and heart spend itself in ministering to those for whom He died. If the church was the body of which Christ is the head, that body could not be divided; hence the increasing ecumenical interest. Only as the body of which Christ is the head can the church fulfill its appointed mission—"that the world may believe that thou hast sent me" (John 17:21).

This concern for the faith was one of the main reasons for the organization of the General Conference. The Conference constitution, in all revisions, as also that of 1950, in Article III spoke of the origin and growth of the Conference as a result of "a deeply felt desire for closer union of individual congregations in order: (1) to establish more firmly and to deepen the basic Christian faith and (2) to testify to its relevance to all of life."

This "basic Christian faith" is further elaborated in Article IV, under the heading "Our Common Confession," as follows:

"The General Conference believes in the divine inspiration and the infallibility of the Bible as the Word of God and the only trustworthy guide of faith and life; and in Jesus Christ as the only Saviour and Lord. 'Other foundation can no man lay than that is laid, which is Jesus Christ' (1 Corinthians 3:11). "In the matter of faith it is, therefore, required of the congregations which unite with the Conference that, accepting the above confession, they hold fast to the doctrine of salvation by grace through faith in the Lord Jesus Christ (Ephesians 2:8, 9; Titus 3:5), baptism on confession of faith (Mark 16:16; Acts 2:38), the avoidance of oaths (Matthew 5:34-37; James 5:12), the Biblical doctrine of nonresistance (Matthew 5:39-48; Romans 12:9-21), nonconformity to the world (Romans 12:1, 2; Ephesians 4:22-24), and the practice of Scriptural church discipline (Matthew 18:15-17; Galatians 6:1).

"The General Conference believes that membership in oath-bound secret societies, military organizations, or other groups which tend to compromise the loyalty of the Christian to the Lord and His Church is contrary to such apostolic admonition as: 'Be ... not unequally yoked ... with unbelievers' (2 Corinthians 6:14, 15), and that the church 'should be holy and without blemish' (Ephesians 5:27)."

A second characteristic of the conference was the emphasis on freedom and autonomy—Christian freedom, not license, for the individual, and autonomy for the congregation. Each believer stood before God Himself in faith as a free individual, uncoerced by other believers. Each individual soul, created in the image of God, was competent and responsible to deal directly with God through Christ, without intervention of parent, priest, sacrament, church, or state. This personal responsibility to God was the basis for freedom of conscience. This was true, within limits, in both faith and practice.

The chief interest in autonomy was not in property rights, or any other material aspect. It was rather a matter of the spirit. The local congregation must be free and autonomous "so that it may move to some mountain of transfiguration or to some upper room at Pentecost." Nicholas Berdyaev was reported to have said that "freedom is a burden rather than a right, a source of tragedy and untold pain." Freedom was not only to be free from something, but also to be free to something. This involved duty and responsibility.

Of the larger free churches in America, General Conference Mennonites in polity were probably most like the Baptists and Congregationalists. The feeling of affinity with these groups was indicated by the fact that their colleges and seminaries often were the choice of Conference young people not attending their own, both in earlier years before General Conference schools existed and even in the 1950s. A number of early and later Conference leaders attended schools at Oberlin, Rochester, and Chicago. Some Methodist schools, such as Garrett, were also chosen, but very few went to Presbyterian or Southern Baptist schools was is the case in some other Mennonite groups.

In the mid-20th century the Conference was moving toward a closer and more integrated organization, including headquarters and executive secretaries, all of which was needed, but which also had its distinct dangers.

The Conference began with unity of all Mennonites in America as one of its goals, as was indicated by the very name that was adopted. It has always been in the forefront in inter-Mennonite cooperation, such as hospitals, old people's homes and orphanages, Civilian Public Service, relief work of various kinds, all-Mennonite conventions, and Mennonite cultural conferences.

The fellowship with other Mennonite groups as well as with non-Mennonite Christians, was indicated by the practice of open communion and the former membership in the Federal Council of Churches. General Conference ministers usually participated in local interdenominational ministerial associations, and congregations fellowshiped with others in summer Sunday evening services in most towns where they were located. The colleges regularly employed teachers not only of other Mennonite groups but also some non-Mennonite Christians.

An open fellowship has its dangers. Because of this the Conference was more open to some of the non-Mennonite ideas and practices that have here and there caused dissension in congregations, such as child evangelism, eternal security, dispensationalism, materialistic millennial interpretations, various Calvinistic, modernistic, and Fundamentalistic interpretations of Scripture, as well as materialistic influences and trends toward worldliness and secularization.

A fourth characteristic of the General Conference Mennonites was a spirit of dynamics or ability to change. Christian respect for personality was the basic assumption of democracy. The respect for the individual personality underlying democracy was of highest value from the Christian point of view. In democratic America, Mennonites were free to reject change and did so. Because of this inertia they were finally in danger of dying. Oberholtzer and his group recognized this and were willing, at considerable cost, to bring about needed revitalization. In line with this Christian respect for personality most General Conference congregations were giving women as well as men the right to vote. Laymen as well as ministers had a share in the councils of the church. Delegates to conferences were men and women, young and older people, and far more laymen than ordained ministers.

A noticeable change began taking place from a plural, untrained, unsalaried ministry to a single, salaried, trained minister for each congregation; from an elder in charge of more than one meeting place to an elder for each congregation, and from different levels of ordination as evangelist, preacher, and elder to one full ordination. Socially the Conference changed from the position that life insurance and political voting were evil and thus to be shunned, to where these were considered not only good, but to be embraced as a Christian duty. The rural-urban trend with all its implications and many other changes affected the Conference.

Finally and above all, from the very formation in 1847-60 until the 1950s, the General Conference Mennonites were always characterized by a deep sense of mission. As a part of this sense of mission there was a strong emphasis on consistent everyday Christian living of every Christian all through the history of the General Conference. It was considered important to believe right, but this faith must also issue in living and doing right. This living right goes deeper and means more than conforming to any outward rules and regulations. Not that one can earn anything in God's sight by living right, but it is an expression of gratitude for salvation through Christ Jesus. He is not only our Saviour but also the Lord of everyday decisions and ordinary living. The Gospel is not only to be brought into all the world geographically, but also to penetrate all levels and areas of personal and corporate life on earth.

Conference Leadership

It is impossible to list all who have served as leaders in Conference affairs in one area or another. Here follows a partial list with some attempt to classify them according to the area in which they rendered outstanding service.

Conference Leaders: P. R. Aeschliman, John B. Baer, J. J. Balzer, Peter Balzer, Jacob Buller, Walter Dyck, Benjamin Ewert, Allen M. Fretz, Dietrich Gaeddert, David Goerz, W. S. Gottshall, Daniel Hege, Michael Horsch, Ephraim Hunsberger, Cornelius Jansen, Jacob H. Janzen, Maxwell Kratz, Christian Krehbiel, Henry J. Krehbiel, Olin Krehbiel, W. W. Miller, John Moser, John H. Oberholtzer, H. D. Penner, Johannes K. Penner, Abraham Ratzlaff, P. K. Regier, Heinrich Richert, P. R. Schroeder, Andrew B. Shelly, Anthony S. Shelly, Christian Schowalter, C. H. A. van der Smissen, I. A. Sommer, Samuel F. Sprunger, Joseph Stucky, Jacob Stucky, L. Sudermann, J. J. Thiessen, David Toews, Emanuel Troyer, B. Warkentin, P. P. Wedel.

Leaders in Missions, Education, and Publication: Henry J. Brown, N. E. Byers, D. H. Epp, H. H. Ewert, H. A. Fast, I. I. Friesen, S. J. Goering, Mrs. R. A. Goerz, N. B. Grubb, Gustav N. Harder, J. E. Hartzler, G. A. Haury, Mrs. S. S. Haury, Samuel S. Haury, N. C. Hirschy, Lester Hostetler, Ed. G. Kaufman, Frieda Kaufman, John W. Kliewer, Cornelius Krahn, H. P. Krehbiel, A. E. Kreider, J. H. Langenwalter, J. F. Lehman, Samuel K. Mosiman, S. F. Pannabecker, Peter A. Penner, Peter W. Penner, Rudolphe Petter, Jacob Quiring, L. L. Ramseyer, J. M. Regier, J. G. Rempel, Peter H. Richert, C. J. van der Smissen, C. Henry Smith, J. N. Smucker, J. R. Thierstein, John Thiessen, John Unruh, Catherine Voth, Henry R. Voth, Abraham Warkentin, C. H. Wedel, D. C. Wedel, Peter J. Wiens.

General Conference Mennonite Church Congregations and Membership, 1955

| District | GCMC

Congregations | Non-GCMC

Congregations | GCMC

Members | Non-GCMC

Members | Children

(Unbaptized) | Total

Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canadian | 49 | 22 | 12,810 | 1,195 | 8,425 | 22,430 |

| Central | 19 | 1 | 3,020 | ? | 642 | 3,662 |

| Eastern | 28 | 0 | 4,558 | 0 | 1,519 | 6,077 |

| Middle | 20 | 0 | 5,258 | 0 | 1,951 | 7,209 |

| Northern | 26 | 5 | 5,605 | 395 | 2,926 | 8,926 |

| Pacific | 21 | 2 | 3,280 | 64 | 904 | 4,248 |

| Western | 66 | 0 | 13,584 | 0 | 5,045 | 18,625 |

| Total (North America) | 229 | 30 | *48,115 | 1,654 | 21,412 | 71,181 |

| South America | 5 | 0 | 1,989 | |||

| Total | 234 | 30 | 50,004 |

- This is not an accurate figure as 6 churches did not report. The total North American membership was probably somewhat over 50,000. -- Edmund G. Kaufman

See also Conference of Mennonites in Canada

Bibliography

Barrett, Lois. The Vision and the Reality: The Story of Home Missions in the General Conference Mennonite Church. Newton, Kan.: Faith and Life Press, 1983.

CMC Directory (1998): 85-96.

Conference Reports and Minutes of Triennial Sessions (1953 ff.).

Constitution of the General Conference Mennonite Church. Newton, KS, 1950.

Commission and General Secretary's Reports (annually, 1953 ff).

Fretz, J. W. "Reflections at the End of a Century." Mennonite Life 2 (July 1947).

Handbook of Information (1953-1998).

Haury, David. Prairie People [Western District]. Newton, 1981.

Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. Mennonitisches Lexikon, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. I, 29-32.

Juhnke, James C. A People of Mission: A History of General Conference Mennonite Overseas Missions. Newton, Kan.: Faith and Life Press, 1979.

Kauffman, J. Howard and Leland Harder, eds., Anabaptists Four Centuries Later: A Profile of Five Mennonite and Brethren in Christ Denominations. Scottdale, Pa.: Mennonite Publishing House, 1975.

Kaufman, Ed. G. The Development of the Missionary and Philanthropic Interest Among the Mennonites of North America. Berne, IN, 1931,

Kaufman, Ed. G. "The General Conference of the Mennonite Church of North America." Menn. Life 1 (July 1947).

Krehbiel, H. P. The History of the General Conference of Mennonites of North America, 2 vols. St. Louis, Missouri, USA); Newton, KS, 1898-1938.

Kreider, Robert. Where Are We Going? Schowalter Memorial Lecture given at the 1971 triennial session in Fresno, California (Newton, 1971).

Mennonite World Handbook (MWH), ed. Paul N. Kraybill (Lombard, Ill.: Mennonite World Conference (MWC), 1978): 344-51; MWH, (Strasbourg, France, and Lombard, Ill.: MWC, 1984: 145.

Mennonite Yearbook & Directory (1997): 132.

Pannabecker, S. F. "The Anabaptist Concept of the Church in the American Mennonite Environment." Mennonite Quarterly Review 25 (January 1951).

Pannabecker, S. F. "The Development of the General Conference of the Mennonite Church of North America in the American Environment." Yale University Ph.D. dissertation.

Pannabecker, S. F. "John H. Oberholtzer and His Time—A Centennial Tribute 1847-1947." Mennonite. Life 2 (July 1947).

Pannabecker, Samuel Floyd. Faith in Ferment: A History of the Central District Conference. Newton, 1968.

Pannabecker, Samuel Floyd. Open Doors: History of the General Conference Mennonite Church. Newton, 1975.

Reports of Women in Mission and the Women's Missionary Association (1953 ff.).

Ruth, John L. Maintaining the Right Fellowship [Eastern District]. Scottdale, 1984.

Sawatsky, Rodney J. Authority and Identity: The Dynamics of the General Conference Church. Bethel College, 1987.

Shelly, Paul R. Religious Education and Mennonite Piety Among the Mennonites of Southeastern Pennsylvania: 1870-1943. Newton, KS, 1952.

Smith, C. Henry. The Story of the Mennonites. Newton, KS, 1950.

Wenger, J. C. "Mennonites Establish Themselves in Pennsylvania." Mennonite Life 2 (July 1947).

Additional Information

Resolutions approved by the General Conference Mennonite Church

- Our Common Confession (General Conference Mennonite, 1896)

- Statement of Doctrine (General Conference Mennonite Church, 1941)

- A Statement of the Position of the General Conference of the Mennonite Church of North America on Peace, War, Military Service, and Patriotism (General Conference Mennonite Church, 1941)

- A Christian Declaration on Peace, War, and Military Service (General Conference Mennonite Church, 1953)

- Statement on the Believers' Church (General Conference Mennonite Church, 1956)

- The Christian and Nuclear Power (General Conference Mennonite Church, 1959)

- The Christian and Race Relations (General Conference Mennonite Church, 1959)

- A Christian Declaration on Communism and Anti-Communism (General Conference Mennonite Church, 1962)

- A Christian Declaration on the Authority of the Scriptures (General Conference Mennonite Church, 1962)

- The Christian Family (General Conference Mennonite Church, 1962)

- A Christian Declaration on Capital Punishment (General Conference Mennonite Church, 1965)

- Resolution on Nationalism (General Conference Mennonite Church, 1968)

- Resolution on World Hunger (General Conference Mennonite Church, 1968)

- The Way of Peace (General Conference Mennonite Church, 1971)

- A Christian Declaration on Amnesty (Mennonite Central Committee, 1973)

- A Statement of Direction to Guide Congregations and Regional Conferences in Understanding Ordination (General Conference Mennonite Church, 1974)

- The Call and Care of Pastors (General Conference Mennonite Church, 1977)

- Christian Stewardship of Energy Resources (General Conference Mennonite Church, 1977)

- Church Planting (General Conference Mennonite Church, 1977)

- Governmental Oppression and our Christian Witness (General Conference Mennonite Church, 1977)

- Offender Ministries (General Conference Mennonite Church, 1977)

- Television Violence (General Conference Mennonite Church, 1977)

- Guidelines on Abortion (General Conference Mennonite Church, 1980)

- Legal and Legislative Exemptions from War Tax Withholding (General Conference Mennonite Church, 1980)

- Justice and the Christian Witness (General Conference Mennonite Church, Mennonite Church, 1983)

- Mennonite Tricentennial Resolution (General Conference Mennonite Church, 1983)

- Resolution on Central America (Mennonite Church, General Conference Mennonite Church, 1983)

- A Resolution on Faithful Action Toward Tax Withholding (General Conference Mennonite Church, 1983)

- Resolution Regarding Caring Community (General Conference Mennonite Church, 1983)

- Statement on Inter-Mennonite Cooperation in North America (General Conference Mennonite Church, Mennonite Church, 1983)

- A Call to Kingdom Commitments (General Conference Mennonite Church, 1986)

- Many Peoples Becoming God's People (General Conference Mennonite Church, 1986)

- Resolution on Apartheid (General Conference Mennonite Church, 1986)

- Resolution on Human Sexuality (General Conference Mennonite Church, 1986)

- A Church of Many Peoples Confronts Racism (General Conference Mennonite Church, Mennonite Church, 1989)

- Recommendation on Exploring MC/GC Integration (General Conference Mennonite Church, Mennonite Church, 1989)

- Resolution on the 500th Anniversary of Columbus (General Conference Mennonite Church, 1989)

- Stewardship of the Earth: Resolution on Environment and Faith Issues (General Conference Mennonite Church, Mennonite Church, 1989)

- A Resolution against Interpersonal Abuse (General Conference Mennonite Church, 1992)

- A Resolution on Health Care (General Conference Mennonite Church U.S. Assembly, 1992)

- A Resolution to Laugh with Abraham and Sarah (General Conference Mennonite Church, 1992)

- Affirming Peacemaking as it Relates to the Peace Tax (U.S.)/Peace Trust (Canada) (General Conference Mennonite Church, 1995)

- Agreeing and Disagreeing in Love -- Commitments for Mennonites in Times of Disagreement (General Conference Mennonite Church, Mennonite Church, 1995)

- Confession of Faith in a Mennonite Perspective (1995)

- Vision: Healing and Hope (1995)

- "And No One Shall Make Them Afraid" (Zephaniah 3:12-13): a Mennonite Statement on Violence (Mennonite Church, General Conference Mennonite Church, 1997)

| Author(s) | Edmund G. Kaufman |

|---|---|

| Henry Poettcker | |

| Date Published | November 2009 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Kaufman, Edmund G. and Henry Poettcker. "General Conference Mennonite Church (GCM)." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. November 2009. Web. 16 Apr 2024. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=General_Conference_Mennonite_Church_(GCM)&oldid=113376.

APA style

Kaufman, Edmund G. and Henry Poettcker. (November 2009). General Conference Mennonite Church (GCM). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 16 April 2024, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=General_Conference_Mennonite_Church_(GCM)&oldid=113376.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 2, pp. 465-471; vol. 5, pp. 329-332. All rights reserved.

©1996-2024 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.