Germany

1956 Article

Introduction

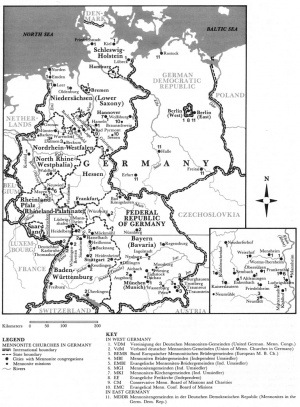

Modern Germany, established as a nation in 1871 by the Treaty of Versailles following the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, suffered considerable territorial loss in the East as a result of defeats in World Wars I (area 180,999 sq. mi. in 1919) and World War II (136,462 sq. mi. in 1946) and in mid-20th century had no territory east of the Oder-Neisse River line. All the German population, with small exceptions, living east of that line was evacuated or expelled westward and was added to the population of the truncated Republic of Germany, with a (1946) population of 65,151,019 excluding the Saar. All the Mennonites who had lived in Danzig and East and West Prussia, as well as those in the three congregations in Poland, were transported westward in this action, some of them later emigrating to Canada and Uruguay. In 1956 the country was still divided into East Germany (Russian Zone) with a population of some 18,000,000, in which there were possibly a maximum of 800 Mennonites of former West Prussian residence, but no organized congregations or ordained ministers, and West Germany with about 47,000,000 and some 15,000 Mennonites (souls). The total number of baptized Mennonites in 1955 in Germany was about 11,500 in 60 congregations. Of these, 18 congregations with some 7,200 baptized members (total 8,700 souls) were in North Germany (above Frankfurt), 36 congregations were in South Germany with about 4,500 baptized members (5,400 souls), of which 18 are in the Palatinate and Hesse with 2,400 members, 9 were in Baden, 6 were in Württemberg, 8 were in Bavaria, and one in Frankfurt, these last 24 congregations having a total of 2,100 members. Of the congregations in North Germany 9 were refugee congregations of former Danzig-West Prussian origin established since 1945. Many such refugees also became members of the old established congregations in both North and South Germany.

The German Mennonite congregations were all (except Frankfurt) members of one of two conferences: (1) Vereinigung der Deutschen Mennonitengemeinden, mostly North Germany with the Palatinate and Hesse, and (2) the Verband Badisch-Württembergisch-Bayrischer Mennonitengemeinden, almost all of whose congregations were in the three last indicated territories. In addition, the Süddeutsche Konferenz included practically all the congregations in the Palatinate and Hesse and in the Verband, although this conference was not quite the same in character as the other two. Most of the congregations of the Palatinate and Hesse were members also of a local conference called the Pfälzisch-Hessische Konferenz. The refugee congregations of the former Danzig-West Prussia area were represented in a ministerial committee called "Aeltestenausschuss der Konferenz der west- und ostpreussischen Mennonitengemeinden." A committee for cooperation in North Germany (Gemeinden-Ausschuss in Nord-deutschland) was formed to help the nine old North German congregations and the nine new North German refugee congregations to work together. A "Mennonitischer Zentral-Ausschuss" served as liaison between the German conferences and the Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) of North America, which conducted relief work in Germany after 1946 and in 1956 had permanent German and European headquarters in Frankfurt (Eysseneckstrasse 54). Four other organizations formed which represented or served all Mennonites in Germany regardless of conference affiliation: (1) Mennonitischer Geschichtsverein, (2) Mennonitisches Altersheim, (3) Mennonitische Siedlungshilfe, (4) Deutsches Mennonitisches Missionskommittee.

The only German Mennonite church paper in 1956 was the Gemeindeblatt der Mennoniten, published since 1870 by the Verband. Der Mennonit (founded in 1948), though printed (at Karlsruhe) and edited in Germany, was published as an international European Mennonite journal by the Mennonite Central Committee (MCC). Full information about the German Mennonite congregations, organizations, and institutions was found in the yearbook, Mennonitischer Gemeinde-Kalender, published since 1892 by the South German Conference. The Mennonitische Geschichtsblätter, founded in 1936, was the organ of the Mennonite Historical Society (Mennonitischer Geschichtsverein).

German Mennonite institutions included four old people's homes in Germany—Leutesdorf, Enkenbach, Pinneberg, and Burgweinting; two relief agencies, Mennonitisches Hilfswerk "Christenpflicht" founded in 1924, and Hilfswerk der Vereinigung der Deutschen Mennonitengemeinden founded in 1947. There was also a Genossenschaftliches Flüchtlingswerk to aid in resettlement of refugees in Germany. Only the Verband has a deaconess work. The Mennonite board of directors of the former Weierhof school (Verein für die Anstalt am Donnersberg) operated a student house (Schülerheim) connected with the public high school (Gymnasium) at Kirchheimbolanden near Weierhof. The Verband had a significant institution in the Bibelheim Thomashof, founded in 1920, a spiritual retreat center.

Anabaptism in Germany, 1525-1650

Introduction

At the time of the rise of Anabaptism (1525-1535) what is now called Germany was a collection of 256 autonomous political units within a loosely organized Empire, called the Holy Roman Empire. Although Switzerland, the Netherlands, and North Italy were technically within the empire, they were actually independent, and the Hapsburg dominions, including Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia, and Lusatia, were outside the orbit of Germany proper. The account of the Anabaptist movement in this article will therefore exclude all these territories. The area "Germany" in the 16th century as it is used here had therefore much the same boundaries as modern Germany 1871-1914, although, not having a unified government, it was broken up into many separate governments with varying religious policies.

The soil in Germany had gradually become rather well prepared for a new religious movement. Already in the late Middle Ages sectarian tendencies had entered Germany (Waldenses, 1211-1480; Brethren of the Common Life since 1401; etc.). Erasmus and Luther, each in his way, were outstanding advocates of church reform. In the early twenties of the 16th century Karlstadt, Müntzer, and the Zwickau Prophets (Storch, etc.) each propagated a reform of his own, which were often wrongly called Anabaptist. Yet it was not the criticism of infant baptism which was decisive, but the introduction of adult baptism. So Anabaptism proper, arising out of Zwingli's reform, was part of the original Reformation movement.

South and Middle Germany

Anabaptism entered Germany first from the South (Switzerland), where it began in Zürich in January 1525. Wilhelm Reublin, appearing in Waldshut from Zürich in April 1525, baptized Dr. Balthasar Hubmaier, the pastor of the Lutheran Church there, and they together baptized most of the congregation, some 360 persons in all. In July Hubmaier published his Von dem Christlichen Tauff der Gläubigen. Other pamphlets by him followed. But in December of that year the Austrians conquered the city and forced Hubmaier to flee, practically ending the Anabaptist congregation. Hubmaier went to Augsburg next, where early in 1526 he established an Anabaptist congregation which became very large and influential, but he went on to Moravia, leaving Augsburg in the hands of Hans Denck, whom he had baptized in May 1526.

Augsburg and Strasbourg now displaced Zürich and Switzerland as the centers of the growing Anabaptist movement, remaining so for some years. Michael Sattler, a noble man of God, became the chief leader in this area of southwest Germany until his execution at Rottenburg in May 1527. He was no doubt the leader of the Schleitheim conference, the first Anabaptist conference, of February 1527, and the author of the notable confession which it produced, the Brüderliche Vereinigung. Hans Denck, who moved about in the area Augsburg-Basel-Strasbourg-Worms, was the leader of a somewhat more mystical-spiritualist wing, but died at Basel in November 1527. He was related in spirit to men like Johannes Bünderlin of Linz, a more radical spiritualist and only for a short time an Anabaptist (1527-1529), Entfelder, likewise only briefly in the movement, and Jakob Kautz of Worms. The Sattler and Denck groups remained separate at Strasbourg, and probably constituted two distinct bodies. Denck preferred the "Inner Word" to the "Outer Word," and taught Christ as a teacher to follow and imitate rather than as a redeemer whose atonement saves men. Jakob Kautz's Seven Theses of 7 June 1527 at Worms also carry this position. Sattler was a full Biblicist and a thorough evangelical.

Meanwhile in 1526-1527 Hans Hut, (d. December 1527 in prison in Augsburg where he had been arrested in September) had become a most effective evangelist for the Anabaptist cause, winning many converts in Swabia, Franconia, Bavaria, Salzburg, and Tyrol. In Augsburg men of note became leaders of the Anabaptist congregation in 1527-1530, like Sigmund Salminger and the patrician Hans Langenmantel. A noted conference was held here 20 August 1527, often called the "Martyrs' Synod" because so many of the missioners sent out from there lost their lives as martyrs within the following years.

Another early center of Anabaptism was found in Hesse, Thuringia, and Franconia, where Thomas Müntzer had had some influence in 1523-1525. Melchior Rinck was the first Anabaptist leader here in 1528-1531 (in prison 1531-1551, where he died) near Hersfeld and Sorga, where there was a congregation. Moravian Anabaptist (Hutterite) influences were strong here for a time, numerous missioners coming here from the base in Moravia, including the noted Peter Riedemann, who wrote his great Rechenschaft, in prison near Marburg (Wolkersdorf) in 1540-1541. Anabaptists were in considerable strength in Hesse as late as 1578, when Hans Kuchenbecker and his brethren drew up an elaborate confession of faith for the authorities (Mennonite Quarterly Review 24, 24-34). Their criticism of the poor quality of life in the state church contributed greatly through Bucer to the introduction of the ceremony of confirmation, which passed from here into other Lutheran and Reformed state churches.

The next outstanding leader to arise was Pilgram Marpeck of Rattenberg on the Inn, converted an Anabaptist in 1528, living in Strasbourg 1528-1532, then chiefly in Ulm and Augsburg until his death at the latter place in 1556. He was the most notable doctrinal writer of the South German Anabaptists (see his Vermahnung of 1542 and Verantwortung of 1544, both against Caspar Schwenckfeld, and his Testamentserläuterung of much the same time). He was the leader of a strong group, as the recent discovery of some 42 letters by him (found in a Bern library) attests.

As soon as the German authorities, both Catholic and Protestant, became aware of the rising Anabaptist movement, they used every means at their command to destroy it. The first Anabaptist mandates by the Hapsburg rulers appeared in 1527. The notorious edict of the Diet of Speyer, ordering the extermination of the Anabaptists throughout the Empire, was issued 22 April 1529. In explanation of the attitude of the authorities, the close connection between the territorial government and the local church, which was already true at that time, must not be overlooked. It might have been possible to reform the whole of any given territorial church, but only as a whole and only in so far as the authorities thought fit. Luther and Zwingli and their followers had to learn that, and only as far as they learned it did they succeed at least partly. Hubmaier and the Münster Anabapists tried to go the same way, but they failed. And neither a congregation of saints nor the baptism of adults could win public opinion; nonconformity and nonresistance, the refusal of oaths, nonpayment of war taxes, and refusal of public offices, sometimes a leaning toward the revolutionary peasants, sometimes the hope that the coming of the Turks would announce the coming of Christ, made them suspect. And the magistrates felt responsible for the spiritual as well as for the physical welfare of their subjects. The Anabaptists' high morality, courage, and unflinching fidelity to their convictions impressed many again and again, but these were not sufficient to change the attitude of the others in general. So the advice of the Lutheran and Reformed theologians guided by their own creed, and the decisions of the lawyers guided by their tradition, resulted in a persecution with all the cruelty of medieval law and punishment (e.g., to counterfeit a coin was punished by burning at the stake). Hege (Mennonitisches Lexikon III, 6 and 7) for the first 20 years (1525-1544) alone enumerates 110 mandates against the Anabaptists: 27 Swiss, 27 Austrian, 15 Bavarian and Swabian, 16 Franconian, Hessian, Saxon, and Thuringian, 6 Alsatian, 4 Palatine, after 1530 also 8 in the north, besides 7 of the Emperor and the Empire in general. But though the principle of persecution was more or less the same, everywhere the practice showed much variation. The number of mandates also illustrates the number of Anabaptists in the one and the other area. Apart from Reformed Switzerland, the keenest persecutors were the Catholic King Ferdinand I of Austria and the Catholic dukes of Bavaria. Among the Protestant princes the electors of Saxony, supported by their theologians, did not shrink from capital punishment (first case 1530 at Reinhardsbrunn in Thuringia), whereas the Landgrave of Hesse never had an Anabaptist executed and even in cases when Saxony was also concerned he prevailed upon the elector to be content with imprisonment for life (e.g., Fritz Erbe, 1532-1548 at the Wartburg near Eisenach and not far from Reinhardsbrunn). The Counts Palatine in 66 years (1544-1610) several times changed their creed (3 times Lutheran, 3 times Reformed), but the report of 350 killed in the one year 1529 in the Palatinate (at Alzey) is an error, though a smaller number were killed there indeed. The imperial cities followed different policies and were often influenced by the princes near by. At Nürnberg, Franconia, as early as 26 March 1527, an Anabaptist (Wolfgang Vogel) was executed, at Schweinfurt in February 1529 another (Georg Braun). In the bishoprics of Bamberg and Würzburg half a dozen were executed in 1528, and in the margravure of Brandenburg (Ansbach-Bayreuth) also about half a dozen in the same year.

The century from the middle of the 16th to the middle of the 17th records the decline of the Anabaptist movement; the persecution gradually reached its goal. From 1548 to 1650 there were (Hege) only 78 mandates (in sharp contrast to the 110 for only the 20 years 1525-1544), the centers being the same as before; e.g., 24 Austrian and 16 Swiss mandates. In 1592 the last execution occurred (Thoman Haan of Nikolsburg) in Bavaria, in 1618 the last executions (Jost Wilhelm and Christine Brünnerin) at Egg near Bregenz in Vorarlberg (Tyrol), also the last in the Holy Roman Empire. All three were connected with the Hutterites who up to 1620 sent many missionaries from Moravia to the West, as also many from the West at this time fled to Moravia.

Strasbourg long remained a chief meeting place of the Anabaptists. Here important conferences were held in 1555 and 1557, in which the Northern (Menno Simons) doctrines of the Incarnation and of the ban were repudiated by the Southern brethren. The Strasbourg conference of 1568, attended by many ministers and elders from all over southern Germany, dealt chiefly with certain rules of discipline. In 1557 and 1571 there were disputations with the Lutheran and Calvinistic authorities respectively of the Palatinate, the former at Pfeddersheim near Worms, the other at Frankenthal. The protocol of the latter was printed in 1571. Among the 15 Anabaptist participants one came from Andernach in the north, two from Alsace in the south, half a dozen from the Palatinate, one from Heilbronn, and one from Salzburg; two others and two Hutterites served as observers, so to speak.

The story of the Hutterites is a chapter of its own, not to be told here. The history of the Anabaptists in Thuringia came to its end in 1584 (Wappler, Täuferbewegung in Thüringen), that of the Palatinate in 1610 (Hege, Täufer in der Kurpfalz), that of Tyrol in 1626 (Loserth, Der Anabaptismus in Tyrol). By the time of the Thirty Years' War practically all the Anabaptists in South and Middle Germany had been converted, exiled, or executed.

It is rather easy to tell the story of the Anabaptists in North Germany separately from that of those in South and Middle Germany, though of course there are connections, Strasbourg especially being the meeting point.

Northwest Germany

Lower Rhine

In Northwest Germany much the same tendencies were found as in the South. As early as 1522 Dr. Gerhard Westerburg, a patrician of Cologne, was visited by Nicholas Storch, who influenced him against infant baptism. A little later he came in contact with Karlstadt, whose sister he married and whose pamphlets and ideas he propagated. In the autumn of 1524 he even paid Zürich a short visit. But in general the question of baptism became important later in the North than in the South. The first martyrs of the Reformation were Adolf Clarenbach and Peter Fliesteden, both subjects of Jülich-Berg, but executed at Cologne in 1529; at least Fliesteden had a moderate touch of Anabaptism. About the same time (1530) Melchior Hoffman (1495-1543) brought to this area from Strasbourg the idea of Anabaptism and of a special doctrine of the Incarnation initiating Anabaptism here and founding a congregation at Emden, and soon reaching the Netherlands also.

It was characteristic of the situation on the Lower Rhine that the dukes of Jülich-Cleves-Berg-Mark-Ravensberg (Johann III, 1521-1539, Wilhelm V, 1539-1592, Johann Wilhelm, 1592-1609) as well as the elector (archbishop) Hermann of Cologne (1515-1547) were influenced by Erasmus and tried to follow a middle line between Luther and the Roman Catholic Church. But this middle party of reformers failed: the turning point was the war (1543), when the Emperor defeated Wilhelm V, gained Geldern for himself and so for the Netherlands, and enforced a Catholic polity. Later reform endeavors also failed, especially because Wilhelm V was handicapped by an attack of apoplexy in 1566. (It is significant that Wilhelm V was a brother-in-law for some time of Henry VIII of England and Francis I of France, later of Emperor Maximilian II and of Elector— later Duke—Johann Friedrich of Saxony, who in 1547 was defeated by the Emperor.)

The "Aemter" and "Unterherrschaften" into which the duchies of Jülich, Cleves, and Berg were divided allowed the nobility a rather independent position. So the Aemter of Born, Millen, Heinsberg, Wassenberg, and Brüggen in the northwest corner of the duchy of Jülich adjoining the present Dutch province of Limburg along the Maas from Venlo to Sittard became a center of the Anabaptist movement. In 1529-1532 especially the court of the high bailiff (Drost) Werner von Pallant at Wassenberg was a meeting place for several clergymen, most of them from the bishopric of Liege (Campanus, Slachtscaep) and the duchy of Brabant (Roll, Vinne), also from Westphalia (Klopreis), known as the "Wassenberger Prädikanten." Klopreis (d. 1535) had been in touch with Clarenbach; from the common prison at Cologne he was rescued and brought to Wassenberg as the first of this group. Here again the influence of Erasmus was found together with that of Luther and Zwingli, and also spiritualistic tendencies and the rejection of infant baptism. With the exception of Campanus (d. after 1574), the leader, they went from Wassenberg to Münster in 1532-1534, were baptized there, and then were sent as apostles of the kingdom of the saints to Westphalia (Slachtscaep, d. 1534, and Vinne, d. 1534) and to the Rhineland (Klopreis and Roll, d. 1534), all ending as martyrs to their belief.

After the first congregation at Emden (1530), the Lower Rhine-Maas congregation at Maastricht (1530-1535), Cologne (1531), Aachen (1533), and Emmerich (1534) must be recorded. The first martyr of this region who is mentioned in van Braght's Martyrs Mirror is Vit to Pilgrams at München-Gladbach (not 1532, as is said there, but 1537).

At Münster (Westphalia) at first a local movement for religious and social reform was started by the Lutheran pastor Bernhard Rothmann and the merchant Bernhard Knipperdolling. Roll as the first of the Wassenberger preachers had already introduced their vision in 1532. Then, after Melchior Hoffman was imprisoned (for life, as it turned out) at Strasbourg in 1533, the Dutch Anabaptists took the lead. As Hoffman had thought of himself as Elijah and Strasbourg as the New Jerusalem and of the millennium immediately following his imprisonment, now the baker Jan Matthijsz van Haarlem declared himself to be Enoch, and Münster the New Jerusalem. The Anabaptist movement here became militant, and at the same time baptism became a political rather than a religious symbol. In February 1534 Matthijsz himself arrived at Münster (which now was besieged by the Catholic and Protestant princes of this region), and was killed in action at Easter (April 5) 1534. But one of his disciples, Jan Beukelszoon of Leiden, a tailor, full of eloquence and courage, under war conditions set up a dictatorship as King David of Zion. Discipline was enforced, communism and polygamy introduced, help asked from abroad. The fact that "banners were to fly in Friesland and Holland, Limburg and Jülich," shows what districts were expected to support the enterprise. But through famine and treason the city fell on 25 June 1535. Münster became Catholic again and many executions followed; Beukelszoon and Knipperdolling died not before 22 January 1536. The Münster catastrophe once more strengthened the hostile attitude of public opinion and of the authorities against Anabaptism of all kinds.

It was Menno Simons (1496-1561) in Holland and North Germany who after the debacle gathered the nonresistant Anabaptists (for him they were named Mennonites after 1544). Soon he had to leave the Netherlands and found a refuge in East Friesland, where in January 1544 he had a disputation with John á Lasco, the reformer of the district. Then he had to leave East Friesland and went to the Lower Rhine-Maas area, where the endeavors to introduce the Reformation had not yet come to an end. Menno stayed and worked "in the diocese of Cologne" in 1544-1546. In vain he strove for a disputation with the "scholars" at Bonn (electorate of Cologne) and at Wesel (duchy of Cleves). But about 1545 he lived with Lemken (see below) at Illikhoven (one part belonging to the Amt Born, duchy of Jülich, another part belonging to Roosteren in the duchy of Geldern) and Vissersweert on the Maas (Amt Born), now both in the Dutch province of Limburg. He preached in the environs of both places and also reached Roermond and may have founded the Anabaptist congregation of Illikhoven-Vissersweert. At any rate after the Wassenberg preachers and their adherents had left for Münster, and Menno had visited the region, organized congregations remained or were founded anew.

Roelof Martens, usually called Adam Pastor, had been ordained as elder by Menno (in 1542?) and excommunicated by Dirk Philips and Menno in 1547. Nevertheless he continued his work in his district from Overijssel in the Netherlands to the county of Mark (Hamm) in Westphalia, having his seat at Odenkirchen (exclave of the electorate of Cologne), and at Well on the Maas (duchy of Geldern), here and there under the protection of a member of the van Vlodrop family. Menno and Adam diverged from the orthodox Christology in opposite directions. In Jesus Christ Menno, following Melchior Hoffman and Obbe Philips (d. 1568), overstated the divine nature, and Adam the human one. The idea of a pure congregation called for a divine head of the church; the idea of an imitation of Christ called for a human head. Matthias Servaes, ordained by Zillis (see below), and Heinrich von Knifft worked especially in the area of München-Gladbach; Matthias Servaes worked also at Cologne, where he was executed in 1565.

More to the South, in the Aemter Born, Millen, etc., of the duchy of Jülich the records showed an office of teaching and baptizing and of deacons for the poor. About 1550 an elder Leitgen died, and in 1550 the "principal teacher" Remken Ramakers was executed at Sittard, Amt Born. They were succeeded by Theunis van Hastenrath, who had his seat at Illikhoven and worked from the Maas to the Rhine (from Kleve to Essen and from Maastricht to Bonn), being executed at Linnich on the Roer in 1551. He was succeeded as elder by Lemken, formerly deacon at Vissersweert in 1547 and at Illikhoven in 1550, working at first in the western Aemter of the duchy of Jülich and along the Maas, later also in a wider area.

Farther to the South, in the Amt Montjoie in the Eifel Mountains, Zillis, another elder, was found who together with Lemken (and the Dutch Waterlanders and the South German Anabaptists) fought the rigid attitude of Menno concerning excommunication and shunning from 1557 to 1560, when Menno excommunicated Lemken and Zillis as well as the Waterlanders. Thus Menno and his friends on the one side, and the Waterlanders, the "High Germans" (Lemken and Zillis in Jülich), and the Southern Anabaptists on the other side, were separated. Zillis worked in the duchy of Berg on the right side of the Rhine as well as in the duchy of Jülich on the left side. There were martyrs, e.g., Palmken Palmen (1550) at Born, Maria of Montjoie (1552) at Jülich, and Conrad Koch (1565) at Honnef in the duchy of Berg. Thomas von Imbroich from Imgenbroich near Montjoie was executed at Cologne in 1558. Some Hutterite missionaries were executed in 1558-1559 at Aachen.

In spite of such sacrifices (or because of them) the congregations on the Lower Rhine in general held their own to the end of the 16th century and into the 17th, not being exterminated as was the case in Middle Germany and to a large extent in South Germany. In May 1591 a decisive meeting took place at Cologne under the guidance of Leenaert Clock. Congregations of the Upper Rhine, Breisgau, Alsace (Strasbourg, Weissenburg), and the Palatinate (Kreuznach, Landau, Landesheim, Neustadt, Worms) were represented. Of the Lower Rhine the congregations of the city of Cologne, of the electorate of Cologne (Odenkirchen), of the duchy of Cleves (Rees), of the duchy of Jülich (area of Milien and Maas, München-Gladbach), and of the duchy of Berg were represented. Practical questions prevailed, but some doctrinal questions appear in the first part of the Concept of Cologne. If on the one side the Trinity was confessed, on the other side the Holy Spirit was described as a power of God (and so not as the third person of the Trinity). He who was baptized according to Anabaptist order was not to be rebaptized.

The 17th century put these congregations under new conditions. Anabaptists were in general expelled in 1601 from the cities of Aachen and Cologne, in 1614 from Burtscheid (then belonging to the Imperial Abbey of Cornelismünster, now incorporated into Aachen), and in 1628 from Odenkirchen. In 1614 the united duchies were divided into tolerant Cleves under the Hohenzollerns and intolerant Jülich-Berg under the Wittelsbachs. From 1600 on the county of Mors with the dominion of Krefeld for a century belonged to the tolerant House of Orange. Thus, early in the 17th century a congregation was founded at Krefeld, which now became the place of refuge for Mennonites on the Lower Rhine, as well as some congregations in the duchy of Cleves (Goch, Kleve, Emmerich, Rees, Duisburg). It is worthy of note that the founder of the congregation of Krefeld, Hermann op den Graeff (1585-1642), together with a second representative, Wilhelm Kreynen, signed the Confession of Dordrecht in 1632.

East Friesland

East Friesland remained a place of refuge for the Anabaptists, first in the country, especially near Krummhorn. Later there were three congregations of importance besides Emden: Norden, Leer, and Neustadt-Gödens. In 1612 there were a total of about 400 Anabaptists in East Friesland. There were also some across the eastern border in the county of Oldenburg. Among the first grants of toleration for Mennonites is that given by Count Rudolf Christian in 1626 for his country. Emden reached the climax of its history in the 16th century. Situated next to the Netherlands, but maintaining its independence, it was again and again (like Wesel in a similar situation) used as a starting point by the Anabaptists for influencing the Netherlands from the outside. In 1568 and 1579 meetings of the Waterlanders were held at Emden. In 1571 a Reformed synod took place there. In 1578 there was a religious disputation between the Flemish Anabaptists and the Reformed, of which the Protocol was published in 1578; from Cologne and Groningen Anabaptist elders were present. For years Leenaert Bouwens had his headquarters at 't Falder near Emden, and baptized 320 persons here alone, in other places of East Friesland also 323, but during 1551-1582 many more in the Netherlands and a few also in Cologne, Holstein, and Mecklenburg. It is also probable that many refugees from here found their way eastward—a few, as said before, to the adjacent Oldenburg, but practically none to the district between the Weser and the Elbe (the archbishopric of Bremen).

Holstein and Prussia Proper

The two duchies of Schleswig and Holstein, the dominion of Pinneberg, and the two imperial cities and Hanseatic towns of Hamburg and Lübeck were the goal for many. The first place in this area where Anabaptists were to be found was Lübeck. Here in 1535 the burgomaster Jürgen Wullenweber (d. 1537) took a friendly attitude toward the Anabaptists. As early as 1532 Cord Roosen (1495-1553 or 1554) of Korschenbroich near Grevenbroich (near München-Gladbach), had found his way to Lübeck. His sons and a grandson were, surprisingly, powder manufacturers. In 1546 Menno Simons held a meeting here concerning David Joris (d. 1556), and in 1552 concerning Adam Pastor. In the winter of 1553-54 Menno was living at neighboring Wismar in Mecklenburg, where he debated with the Reformed preacher Micronius (d. 1559). Here the Wismar articles were adopted in 1554. Later Menno, with the Anabaptist printing plant recently founded at Lübeck, went to Fresenburg near Oldesloe between Lübeck and Hamburg. Here arose the first congregation (Flemish) in this area; and here Menno found an abode undisturbed by the authorities for his last years (1554-1561).

In the second half of the 16th century the Anabaptist impact more and more shifted from the eastern to the western part of this area. During the same time here and often elsewhere it also changed its character more and more: Anabaptists were becoming Mennonites. The struggle for a new vision was disappearing, though the loyalty to convictions remained. While Baptists and Quakers soon undertook to propagate the one or other of these convictions, the Mennonites were content to have permission to live according to their convictions, and in addition to be good manufacturers or farmers and citizens. This development may be the consequence of a colonial existence, of a flight into another country, where first a living had to be made.

On the west coast of Schleswig-Holstein the first Mennonites (as we now may call them) appeared sometime before 1566 when five of them had already been exiled, on the peninsula of Eiderstedt in the duchy of Schleswig, not far from the border of the duchy of Holstein, belonging to the Gottorp portion. Soon there were wholesale merchants, among them Johann Clausen Codt (also Kotte, Cotte, Cothe, Coodt), a dike-reeve who, like Marpeck, early in the 17th century sustained the religious wishes of his fellow believers by protecting the land and so being very helpful to the country. In 1621, when Duke Friedrich III of Holstein-Gottorp (1616-1659) founded Friedrichstadt east of Eiderstedt as a Dutch place of refuge, he gave the Mennonites very liberal privileges. Some years earlier already (1616) the king of Denmark, who with the Gottorps and (until 1640) the counts of Schauenburg (dominion of Pinneberg) shared the whole country, had founded Glückstadt on the Elbe, south of Friedrichstadt, as a place of refuge; here from 1623 on Mennonites were accepted as citizens and from 1631 on were mentioned in a grant of toleration for "the Dutch nation" in the city. But the greatest importance for the Mennonites in this area was gained by Hamburg, the imperial city, and the adjacent Altona, first a village of fishermen, since 1604 a borough in the county of Pinneberg under the Schauenburgs, after 1640 under the kings of Denmark, after 1664 a town under municipal law. By 1575 Mennonite families were found at Hamburg (de Voss, Quins, etc., coming from the Netherlands), and 1601 at Altona (Francois Noe II, whose father had come from Antwerp to Hamburg, originally from Flanders). At Hamburg the Mennonites made a contract with the city in 1605 (renewed in 1635). Noë as a wholesale dealer had come in touch with Ernst, Count of Schauenburg, and was allowed with others to settle on the "Freiheit" next to Hamburg. He obtained a "privilege" for his coreligionists in 1601 (renewed in 1635 and again in 1641). Though living in different states (until 1937, when Altona was incorporated into Hamburg), the Mennonites of the two places had no separate congregations.

A still larger colonization enterprise of Dutch Mennonite refugees were the settlements in Prussia proper, the German melting pot. In Ducal (or East) Prussia the Duke, himself excommunicated by the Pope and outlawed by the Emperor, even had councilors with an Anabaptist past, from 1536 Christian Entfelder, the pupil of Denck, from 1542 Gerhard Westerburg, the pupil of Storch and Karlstadt, baptized at Münster in 1534. Immigrants were Schwenckfelders (since 1527), Dutch Sacramentists (since 1527), Gabrielites (1535), Bohemian Brethren (1548), and from ca. 1535 Dutch Anabaptists, who settled especially at Königsberg and in the district of Preussisch Holland near the border of Royal (or Polish or West) Prussia. After the church inspection (the duke was now following a Lutheran course) in 1543 they were exiled; only a few remained. As the devastation in consequence of the "Reiterkrieg" (1519-1525) opened the door for immigrants into East Prussia, so the floods of the Vistula (1540-1543) did the same in West Prussia; here the immigrants were expected to drain the inundated land. The first contract was made in 1547 for the Danzig Werder or delta (Reichenberg, etc.) by Philip Fresen of Edzema, another in 1562 for the Great Marienburg (Unter) Werder by the Loysen brothers at Tiegenhof. In the same period Mennonite settlers reached the cities of Danzig and Elbing as well as the lowland to the left and the right of the Nogat (Ellerwald, Little Marienburg Werder) and somewhat later also the pastures of the Great Marienburg (Ober) Werder at Heubuden. Rather early there were Mennonites also along the Vistula up to Thorn. Menno visited "the elect and children of God in Prussia" in the summer of 1549 and wrote them a letter in the autumn of that year. Later Dirk Philips (d. 1568), its founder, was at the head of the Danzig congregation. A successor of his, Quirin Vermeulen (also "van der Meulen"), in 1598 published a stately edition of the Bible in Dutch translation (the Biestkens Bible).

In 1608 at the diet at Graudenz, the Bishop of Culm, Poland, Laurentius Gumbicki, made a statement to the effect that the Marienburger Werder was filled with Anabaptists. Yet it is reported that at least 80 per cent of the Mennonite farmers had perished of marsh fever in connection with the work of draining and clearing the land. In 1642 King Ladislav IV of Poland (1632-1648) gave the Mennonites a grant of privileges in which he declared that King Sigismund Augustus (1546-1572) had summoned the Mennonites into a district "which then was a desolate swamp and not used. With great effort and large expenditure they had made this district fertile and profitable by turning woodland into arable land and establishing pumps in order to remove the water from the inundated grounds covered with mud and to erect dikes against the floods of the Vistula."

Mennonitism in Germany, 1650-1800

Introduction

We have already observed that from the second half of the 16th century the Anabaptist type more and more died out in Germany and was replaced by the Mennonite type. As evangelization and with it conversion and martyrdom disappeared, with later generations rebaptizing disappeared also, occurring only here and there within the Mennonite groups and being plainly replaced by adult baptism of the following generation when grown up. Thus the imperial mandate of 1529, so to speak, lost its objective; in 1768, for instance, the Imperial Court at Wetzlar even recommended that the affirmation of a Mennonite might be regarded the same as the oath of another. Thus the original endeavor to better the Christian testimony to the world, so much resented by this world, was toned down into the desire of a small religious group to be allowed to live for itself, yes, according to its tradition. And this nonconformity to the world was precisely what made these believers the best farmers, artisans, manufacturers, etc., now highly esteemed by the rulers in this period. So wanderings continued from territories where the Mennonites were persecuted as heretics to other territories where they were welcomed as good citizens. The interest of the world turned more and more from religious problems to economic ones, the Thirty Years' War being the boundary between the older and the newer attitudes.

Migrations

Going from southwest to northeast, there are the migrations of the Swiss Brethren to the Palatinate, where after the devastations of the Thirty Years' War Elector Karl Ludwig (1617-80) gave them a Privilegium in 1664. As early as 1652 they are found near Sinsheim (east of the Rhine, Kraichgau, now Baden-Württemberg) and soon afterwards on the Ibersheimer Hof (west of the Rhine, now Rheinland-Pfalz). The nobility of the Kraichgau between Heidelberg and Karlsruhe opened their domains to the Swiss refugees, as did also Alsace and at least from the beginning of the 18th century also the margraves of Baden-Durlach.

For many of the Swiss emigrants the new home was of rather short duration because of the war of the Palatine Succession (1688-1697). The French invaded and devastated the territory once more, and notwithstanding the Privilegium oppressions were frequendy applied. So from 1707 on many of them searched and found a more lasting place of refuge in Pennsylvania. But many also remained in Germany, some in the Palatinate, some (mostly Amish) crossing the Rhine and the Main to the north and founding (ca. 1750 and later) settlements in Nassau and Hesse, in the county of Wittgenstein (now in Westphalia) and in the county of Waldeck (now in Hesse). Soon afterwards others (Mennonites) turned to the east, to the bishopric of Würzburg (now Bavaria) and the duchy of Württemberg. And when Emperor Joseph II, after gaining Polish Galicia in 1772, invited colonization there in 1781, since the new subjects needed instruction in agriculture, 28 families, most of them Palatines, some of them. Alsatian Mennonites and Amish, settled near Lemberg in 1784.

Farther to the north as early as the 17th century the Mennonites of the duchy of Jülich (1654 from München-Gladbach, 1694 from Rheydt), often linen weavers, found their way to the place of refuge in this region, Krefeld. In addition the (great) Elector of Brandenburg in 1654 and 1660 issued mandates favorable to the Mennonites for his duchy of Cleves, quite contrary to the intolerant mandates of the Wittelsbachs in Jülich. Even in the county of Mark, now also inherited by the Hohenzollerns, a small congregation existed at Hamm (now in Westphalia). A center of its own was Neuwied (founded in 1652 on the Rhine as the new residence of the counts of Wied. Even from the very beginning immigrants of the northern group of Mennonites (Jülich, etc.) and of the southern group (Switzerland, Palatinate) met here. In 1680 they were given a Privilegium, and in 1768 the Count even helped them to get a church, opposite his castle and in the same rococo style of architecture.

Then in the east there was the migration from West Prussia to East Prussia (from 1713 on to the area of Tilsit, and from 1716 on to Königsberg, the attitude of the kings changing, but the local authorities continuing to favor the Mennonites. Later on the Mennonites also moved to the southeast along the Vistula ca. 1750 into Poland proper (Deutsch-Wymysle, and Deutsch-Kazim, to the west in 1765 into the province of Brandenburg (Neumark).

Most settlements in this period secured legal toleration by a grant called a "Privilegium" (concession). Some of these concessions were given by the following rulers: (1) Duke Friedrich III of Holstein-Gottorp, dated 13 February 1623, for Friedrichstadt in Schleswig; (2) Count Rudolph Christian of East Friesland, 26 May 1626, for his country; (3) King Christian IV of Denmark, 6 June 1641, for Altona in Holstein; (4) King Ladislav IV of Poland, 22 December 1642, for his country; (5) Elector Karl Ludwig of the Palatinate, 4 August 1664, for his possessions; (6) Count Friedrich of Wied, 16 December 1680, for Neuwied on the Middle Rhine; (7) King Friedrich Wilhelm I of Prussia, 30 January 1721, for Krefeld. These documents have been preserved in the original or in copies in various archives, most of them also in printed form, some in several editions.

Sometimes older "privileges" were renewed or extended, and also here and there they underwent certain revisions. Sometimes they were limited to a single place (Friedrichstadt, Altona, Neuwied, Krefeld). Elector Karl Ludwig expressly mentioned the protracted war and its effects, and King Christian the importance of the immigrants for trade and commerce. Count Friedrich became the model for other princes of the Empire; he founded the town of Neuwied in the interests of his small territory specifically as a place of refuge for tolerated as well as "privileged" religious groups, hoping to secure as settlers at least part of those "useful" people who had to leave ruined homes elsewhere. The Mennonites were here allowed to conduct their own worship, though it had to be in secret and without making proselytes by "sweet words" (as it is stated in the Altona privilege), and were exempt from attending the worship of the established church, holding public office, bearing arms, and taking the oath. They were even protected against "mockery" (as it is stated in the Friedrichstadt privilege). For all this they only had to be recorded in special registers and to pay a special tax.

The situation of the princes of the Empire in this time as well as their opinions and intentions were rather remarkably revealed by the Neuwied privilege of 1680. The count had asked the Mennonites to attend the official (Reformed) services, but they had asked him to release them from this obligation. So the count pondered and said in his privilege: He was entitled to enforce his requirements, for the imperial law of 1529 expressly forbade tolerating Mennonites in the Roman Empire, and the Peace of Münster of 1648 only permitted Roman Catholics, Lutherans, and Reformed, and even the Imperial Court when authorizing this new residence did not include the Mennonites. But on the other hand they were living quietly, the electors of Brandenburg and the Palatinate and the duke of Holstein and others occasionally tolerated them and so disregarded the law of 1529, and at least he was a free "Imperial Estate" as well, and so by tacit understanding empowered to do the same. And so he gave the privilege in the face of the imperial laws which had settled the problem otherwise. Not the Empire, but the individual territory possessed the real power.

To understand the system of privileges within the territories it must be pointed out that in this period people did not live under equal rights for all, but that rights were differentiated according to the political, social, ecclesiastical, and economic position of the person in question. Thus at Krefeld, e.g., there was no difficulty in releasing the Mennonites from the oath, since the Reformed clergy were liberated from this obligation also, as is seen incidentally from a report concerning the oath of allegiance. Besides, such privileges gave the princes an opportunity to secure able artisans, etc., and in this time of mercantilism it was quite common for princes to attract such persons from one another. Just as arbitrarily as privileges were given, citizenship was also transferred: at Elbing as early as 1585, at Tönning in Eiderstedt in 1607, at Krefeld in 1678, at Königsberg and Marienburg ca. 1750, at Danzig and in Bavaria not before 1800.

Though much scattered by the migrations, under these conditions the Mennonites of Germany reached the culminating point of their history in this period as far as economics were concerned. It may here be sufficient to name David Möllinger (1709-1786), "the father of the agriculture of the Palatinate," the. von der Leyens and the silk industry at Krefeld, the Roosens at Hamburg, and the van der Smissens at Altona, shipowners and whalers of the first rank; or also the gifted mechanic and clockmaker Peter Kinsing (1745-1816) at Neuwied, and the strong Bouman family with its manifold trade at Emden. A real host of Mennonite entrepreneurs at many places promoted the economic advance of their respective areas; kingly merchants they often were, especially in the Lower Rhine district and on the Lower Elbe.

Spiritual Life

As to the spiritual life, the northern settlements (Holstein, etc., and Prussia proper) in the beginning were dependent on the Netherlands, and the southern (Palatinate and its daughter colonies) on Switzerland. The Lower Rhine and East Friesland in their turn were already geographically as neighbors in constant contact with the Netherlands. Visits and exchange of preachers for a long time helped in this direction.

When in the north, e.g., Gerhard Wiebe (Flemish elder of Elbing 1778-1796) had documents copied (Heubudener Urkundenbuch) which he regarded of particular importance also for his congregation and his time, there were among these documents some relating to the division of 1557 (Menno against the Waterlander, Jülich, and South German-Swiss leaders), that of 1567 (Flemish against Frisian), and that of 1586 (Contra-Housebuyers against Housebuyers). In the case of Quirin Vermeulen and Hans von Schwinderen, elder and preacher of Danzig (1583-1588), and for a later controversy at Haarlem in 1631, the documents showed a vivid interchange of opinions and judgments.

So even in 1759 the Dutch divisions were still maintained in East Friesland, in the Holstein region, and in Prussia proper. Old Flemish of the Groningen branch had congregations at Emden, Leer, Neustadt-Goedens, and Norden in East Friesland, and at Przechowka, etc., near Schwetz in Prussia proper. Those of the Danzig Old Flemish branch appear at Danzig, Elbing, Gross-Werder, Heubuden, Königsberg, and Nieschewski near Thorn, all in Prussia proper. The Flemish (alone or combined with Frisians and Waterlanders) had congregations at Emden, Leer, and Norden in East Friesland, at Friedrichstadt and Hamburg-Altona in the Holstein region. Finally the Frisians or Waterlanders (the names change) were represented at Danzig, the Gross Werder (later Orlofferfelde), Lithuania (the Tilsit region), Montau, and Schweinsgrube (later Tragheimerweide) in Prussia proper. At Emden and Hamburg-Altona the congregations had joined the conservative Zonists in 1674 and 1682 respectively. But at Emden and Leer in 1767, at Norden in 1780, and at Danzig in 1808, the congregations were again united.

In 1739 and following years a discipline controversy about wigs, shoe buckles, etc., at Danzig was settled after the Dutch brethren had been asked for their judgment. In 1776 at Hamburg a German translation of the Ris confession of faith (1766 at Hoorn) was published, which remained in use in German congregations until the 19th century.

But soon an independent spirit announced itself among the German Mennonites alongside of the dependency on Dutch developments, especially in literary productions by the settlements on the Elbe and on the Vistula. In 1660 the first German confession of faith appeared at Danzig. Georg Hansen (d. 1703), a shoemaker, from 1655 deacon and preacher and 1690-1703 elder of the Flemish congregation at Danzig, published a catechism in 1671 and a confession of faith in 1678. Gerrit Roosen (1612-1711), a merchant, from 1649 deacon, from 1660 preacher, from 1663 elder of the Flemish congregation of Hamburg-Altona, in 1702 also published a catechism (Christliches Gemütsgespräch) and an apologetic (Unschuld und Gegenbericht). Heinrich Donner (1735-1804), Frisian elder of Orlofferfelde since 1772, and Gerhard Wiebe in 1778 and 1783 published a catechism, which as the Elbing-Waldeck-Zweibriicken catechism was one of the most widely used in Europe and in America. In 1792 Gerhard Wiebe also published a confession of faith.

A new influence from the Netherlands began withe the introduction of trained and salaried ministers, e.g., at Krefeld since 1770, who received their education more and more at the Amsterdam Mennonite Seminary, established in 1735.

In the South the Palatinate Mennonites also showed a continued dependence on Switzerland. Peter Ramseyer (b. 1706), from 1730 preacher and from 1732 elder of the Jura congregation, for 20 years (1762-1782) again and again traveled to the Palatinate to settle dissension there. The Amish division of 1693 especially affected the settlers in the Palatinate. Amish congregations arose by migration from the Netherlands to Volhynia; the most northern points they reached in Germany were Menge-ringhausen in Waldeck, and Petershagen in Minden west of Hanover. The Amish remained in strong contact with each other, at least from Alsace to Waldeck, at meetings where "Ordnungsbriefe" supplemented earlier decisions on discipline. Hans Nafziger, from 1731 preacher and later elder at Essingen in the Palatinate, a central figure in his time, held such meetings at his place in 1759 and 1779. In 1765 he traveled to the Netherlands to settle dissension among the Amish there. In 1780 he published the only edition of the Martyrs Mirror in German in Germany at Pirmasens, together with Peter Weber. In 1781 he wrote a letter to the Amish in Holland as a kind of formulary for baptism, marriage, and ordinations.

Outside Influences

As religious discrimination from 1650 on gradually lost much of its former intensity, the Mennonites could come into contact with religious movements outside their group. In fact, the Mennonite congregations not seldom proved themselves to be a fertile ground for such movements. Among the outside influences were (1) Quakers, (2) Dompelaars, and (3) Pietists.

The Quakers

The Quakers appeared at Kriegsheim in the Palatinate soon after the Mennonites, gained some of them for their convictions, and had a congregation of their own there 1657-1686, when they emigrated to Pennsylvania. They also appeared at Hamburg-Altona in 1659, but not being allowed to stay there soon left again, taking with them some Mennonites, among tliem the preacher Berend Roelofs. They were at Krefeld also in 1667-1683. In the latter year they induced 13 families (formerly Mennonites) to emigrate to Pennsylvania, where they founded Germantown —only one remained Mennonite in the long run; it was the first group of Germans to reach the later United States of America.

The Dompelaars

The Dompelaars were found at Hamburg-Altona in 1648-1746, having their own congregation alongside the Mennonite congregation from ca. 1656 on, their own church building from 1708. Their most prominent preacher was Jacob Denner ( 1659-1746), from 1684, at Lübeck 1687-1694, at Friedrichstadt 1694-1698, at Danzig 1698-1702, and then again at Altona until his death. He preached for an interdenominational audience. Perhaps the group was influenced by the Dutch Collegiants or by the English Baptists. The Dompelaars found at Krefeld in 1705-1725 were of another kind, viz., Dunkers, who in 1719 also turned to Pennsylvania. In the Mennonite congregation at Krefeld for some time one preacher, Gossen Goyen (1667-1737), advocated baptism by immersion, himself being rebaptized in 1724 in the Rhine, and another, Jan Crous (1670-1729), advocated baptism by sprinkling.

The Pietists

The Pietists exercised an especially long and far-reaching influence upon the German Mennonites. It came both from the outside and also through Mennonite channels. In Holland the outstanding Mennonite Pietist was Jan Deknatel (1698-1759), from 1726 the minister of the congregation 't Lam at Amsterdam, converted (in the Pietist sense) in 1734 and standing in close relations with the Moravians and the Methodists. On the Lower Rhine Gerhard Tersteegen (1697-1769), Reformed, from 1725 an interdenominational spiritual adviser, gained a similar position. In 1735-1769 Tersteegen was in close contact with the Krefeld Mennonites and later also with Lorenz Friedenreich (ca. 1728-1794), from 1758 elder of the Mennonite congregation at Neuwied. Friedenreich, in this time of letter writing and traveling and exchange of books and pamphlets, served as a liaison officer in all directions. In his last years Deknatel became instrumental in the conversion of Peter Weber (1731-1781), a weaver and from 1757-1758 until his death preacher of the Mennonite congregation of Höningen near Altleiningen in the Palatinate. Abraham Krehbiel (d. 1804), farmer and preacher (from 1766) of the Mennonite congregation at the Weierhof, was also from his ordination on in contact with Weber, Tersteegen, and Deknatel's son. It was as in a missionary family, and thus also the namelists (Naamlijst), which at Deknatel's instigation were published at Amsterdam from 1731 on, and the endeavor to make them complete, widened the circle more and more. Under the pietist influence even a correspondence between Prussia proper and the Palatinate, so far distant from one another, was started (1768-1773). Hans van Steen (1705-81), elder of the Flemish congregation at Danzig from 1754, and Martin Möllinger (1698-1774), brother of David Möllinger, preacher of the congregation at Mannheim from 1753, were the principal writers. Some letters also came from Gerhard Wiebe (see above) and Frienenreich, Weber, etc. Pietists in West Prussia were Isaak van Diihren (1725-1800), converted in 1772, from 1775 preacher of the Danzig Frisian congregation, who in 1787 published a German extract from the Martyrs Mirror, and Cornelius Regier (1743-1794), from 1764 preacher, 1771 elder of the Heubuden congregation. On the Elbe a stronghold of Pietism was the van der Smissen family, particularly Gysbert III (1717-1793) and his son Jacob Gysbert (1746-1829), who already in 1766-1768 on his cavalier's tour with his cousin Hinrich III (1742-1814) visited in England the great evangelist and cofounder of Methodism George Whitefield, and in Germany Tersteegen and the Moravian settlements, Herrnhut and Niesky. At his advice this cousin in 1781 engaged as a tutor for his many children Johann Wilhelm Mannhardt (1760-1831), a member of the Tübingen Stift, who in 1790 married one of his pupils, thus combining these two families, which were prominent among the German Mennonites, especially in the 19th century.

Assimilation

In addition to these relations with more or less kindred movements the Christian church in general, and the great world also, entered the scene. Gerrit Roosen had already taken a position as a conservative as well as irenical trying to recommend the controversial Mennonite teaching to society as "harmless": Mennonitism in assimilation. At Friedrichstadt two Owens, father and son, were during 1711-1782 successively one of the two burgomasters of the town: public offices were no longer abhorred. In London in 1766 the young van der Smissens enjoyed seeing English soldiers at drill; at Neuwied the young men of the Mennonite congregation in 1804 wanted to meet their new prince on horseback, with swords buckled on, like other young citizens: the principle of nonresistance was at least softened. And even Gerhard Wiebe in his confession of faith of 1792 dropped the idea of a visible congregation of saints and accepted that of an invisible church.

Whereas at Danzig in 1697 the painter Enoch Seemann (b. 1661) was banned for painting portraits (Second Commandment), at Hamburg-Altona Balthasar Denner (1685-1749) and Dominicus van der Smissen (1705-1760), the son and son-in-law of Jacob Denner, were "the last German portraitists of international importance." After the Swedish General Stenbock had burned the town of Altona in 1713, Hinrich I van der Smissen (1662-1737, father of Gysbert III) rebuilt it, thus becoming known as "the city builder." Berend Roosen discovered the famous architect Sonnin and had him build his home, one of the finest in Hamburg in the 18th century. Later the great Mennonite manufacturers gave Krefeld its architectural character by their monumental homes, one of their homes even being called "the castle" (later the town hall).

In 1687 and 1688 the Danzig congregation helped the Jesuits and the Lutherans respectively to build their churches; in 1750-1751 the Hamburg-Altona congregation helped to rebuild the Lutheran St. Michael's Church; in 1779 the Emden congregation shared in the costs of a Reformed peace festival. In 1732 the Danzig Mennonites made a contribution for the Salzburg exiles; for decades the Friedrichstadt Mennonites had done the same for the poor Lutherans of their town. In Krefeld the van der Leyens in 1738 had Roman Catholic, Lutherans, and Reformed among their laborers and in 1789 promoted social contacts between members of different denominations.

In this course of events it is not astonishing to see also the Mennonite church buildings and services adapted to the surrounding culture. Many of the new church buildings—in 1751 Orlofferfelde, 1754 Rosenort, 1768 Fürstenwerder, Heubuden, Ladekopp, and Tiegenhagen, 1776 Gruppe, 1783 Ellerwald (all in West Prussia), 1778 Sembach, 1779 Eppstein, 1784 Heppenheim (all in the Palatinate); also the old churches—1586 Montau, 1618 Schönsee, 1638 and 1648 Danzig, 1675 and 1715 Altona, 1693 Krefeld, 1769 Emden—indeed were modest buildings. But Elbing (1590) and Friedrichstadt (1708) were fine patrician buildings, and Norden (1796) was even a finer one in a splendid rococo style. The Spitalhof (1682) held its services in a beautiful old Gothic chapel. The church of Neuwied (1768) has already been mentioned. Organs were first admitted to German Mennonite churches at Altona (1764) and at Norden (1797).

Language was long a great barrier between the immigrant German Mennonites and the native Protestants or Catholics. This was not so true in the South, where the Swiss dialect was apparently soon given up and the High German literary idiom commonly used from the start, but in the North things were more complicated. The Mennonites from Holland of course brought the Dutch church language of their old home with them into the new one. The congregations on the Dutch-German border so close to the Netherlands, which was enjoying its political and cultural Golden Age in the 17th century, naturally also felt the Dutch influence in the matter of language. Yet naturally in the course of time the Dutch language for church services, in partly alien, partly changed surroundings, with no support from the language in general use, declined and was pushed aside. It is easy to understand that this development took place most rapidly at the most advanced Anabaptist-Mennonite outpost, in West Prussia around Danzig. By 1671 Georg Hansen lamented that the young people read German better than Dutch. So in the rural congregations at Heubuden in West Prussia in the 1750's and the city congregation at Danzig in the 1760s and 1770s the ministers began to preach their sermons in German. Farther to the west the proximity of the Netherlands was of strong influence; also the fact that the educated ministers called by these congregations had to be obtained from the Netherlands or had to get their training in the Dutch universities and especially in the Mennonite Seminary at Amsterdam. In 1786 at Hamburg and Altona Reinhard Rahusen (1735-93) first began the use of High German in the newly introduced weekday services; in general the High German language was not used here in sermons until 1839 and in the church records not until the 1880s. Krefeld used German after 1818, Friedrichstadt after 1826.

Modern Mennonitism in Germany, 1800-1949

Nonresistance, etc.

For the history of the Mennonites in Germany a turning point came when the French Revolution did away with local independence and local privileges, in 1789 proclaiming "Liberty, Equality, Fraternity" as the rights of all men, and in 1793 introducing universal compulsory service. Napoleon moderated this law in 1800 by allowing substitutes under special conditions, but enforced it anew in 1806. Since the treaties of Basel (1795) and of Campo Formio (1797), the Rheinbund (1806), and the treaty of Tilsit (1807) ceded the left border of the Rhine to France and placed practically all Germany west of the Elbe under the control of Napoleon I, similar decrees followed, especially in the South German states.

In the face of this danger to nonresistance the Mennonites of the Palatinate as early as 1802 sought contact with those of the Netherlands. In 1803 and 1805 at Ibersheim representatives of Rhenish congregations professed anew their adherence to the principles of nonconformity and nonresistance. Several delegates were sent to Paris on behalf of their privileges. In vain; no exceptions were allowed, only perhaps substitutes. But to obtain substitutes was rather expensive. Some congregations even regarded paying substitutes as contrary to nonresistance. For some time some of the congregations paid for the poor members who could not pay the substitutes. But later on this practice was discontinued, since nonconcerned members opposed it. So, on the one hand many emigrated to America in 1830-1860; on the other hand, as the conditions continued, those remaining in South Germany gradually gave up the principle of nonresistance. The catechisms of the Palatinate and Hesse (i.e., old Palatinate on the left border of the Rhine) of 1861, and of Baden (i.e., old Palatinate on the right border of the Rhine: the Kraichgau and Baden-Durlach) of 1865 had already tacitly dropped the principle. Early in the 20th century, when Georg Wünsch asked a young farmer in Baden why he did not follow the traditional order, this Mennonite answered, "When every man goes, we can't stay at home."

In North Germany the kingdom of Prussia after the peace of Vienna in 1815 comprised the following Mennonite population: East Prussia 678; West Prussia 12,497; Brandenburg, etc., 692; Rhine Province and Westphalia 1,289, making a total of 15,156 Mennonites (souls). In the Rhine Province alone in 1812-1827, in the government district of Düsseldorf (Krefeld, etc.), Aachen, and Cologne, there were about 883; of Coblenz (Neuwied, etc., and Trier) about 353, including some Amish, making a total of about 1,236 Mennonites (souls).

As to the western provinces of Prussia, their different parts had belonged to various states and were only now united into a larger political body. Since the eastern provinces lived under older decrees, the government, after the Prussian military law of 1814 was promulgated, tried to find a similar status for those of the west. A first report was given by the Minister of the Interior in 1817, a second by a commission of the Royal Council in 1819 (Menno, several confessions including that of Dordrecht and that of Ris, the Latin history by Schijn, works on Mennonites by Zeidler in 1698, Rues in 1743, Crich-ton in 1786, and Starck in 1789, and other general works were cited). There was a lively correspondence between King Friedrich Wilhelm III and the Oberpräsident on the one side, with the congregations, especially Krefeld, on the other. Even a small Amish group at Offhausen (Altenkirchen district) received an answer from Chancellor Hardenberg. In 1826 the king ordered that all heads of Mennonite families be questioned about their position on nonresistance. In 1830 the law on the rights of the Mennonites (and Quakers) in the western provinces and Brandenburg was published. Most of the families asked accepted military service and thus became ordinary citizens. The smaller part refused military service, and were obliged to pay a special income tax of 3 per cent, were not allowed to acquire new property, and were admitted to communal, but not to state offices; new settlements were forbidden. Thus the new legal status was established. In the North as well as in South Germany many, particularly the Amish, emigrated to America in 1830-1860, particularly from Nassau, Hesse, and Waldeck. Among those who remained in Germany there were frequently cases—at Friedrichstadt, at Hamburg-Altona, and in the 1820's even at Krefeld—when individuals more or less successfully tried to evade military service. In Hamburg occurred the remarkable case that in 1818 a Mennonite Lieutenant Jansen complained to the military authorities of being excommunicated by the congregation on account of his military service; it was rather surprising to him that the authorities advised him to return to civilian life. Yet the Hamburg congregation lost ground notwithstanding. Whereas in 1837 they had asserted that substitutes were as objectionable as personal service, by 1851 they had to be satisfied with avoiding personal service by the use of substitutes.

Little by little, as in South Germany, the attitude of the Mennonites in North Germany concerning nonresistance changed. Already in 1831 the congregations of East Friesland (in 1815-1866 belonging to the Kingdom of Hanover) had relinquished this principle, as they then officially declared to the authorities.

In 1848 the first German parliament in the Paulskirche at Frankfurt became something like another turning point in nonresistance. A Mennonite banker of Krefeld, Hermann von Beckerath (1801-1870), a member of diis parliament (and of the Prussian parliament as well) and of its committee for the constitution and even one of its ministers, discussing the fundamental laws, on 28 August declared: "I think myself fortunate in belonging to one of the freest denominations. The time of privileges is gone. The modern state requires equal rights for all citizens. So the Rhenish Mennonites with only few exceptions are rendering their military service. Nonresistance with them is no longer an integral part of their creed." So an amendment in favor of nonresistance for the Mennonites offered by the members from Danzig was lost. Many applauded: a real confession! Indeed, these Mennonites of West and South Germany now regarded nonresistance no longer as a fundamental article of their creed, but as a privilege no longer tolerable because it was injurious to the rights of fellow citizens.

In 1867 even the conference of Offenthal (near St. Goarshausen on the Rhine in Nassau), where Mennonites and Amish of the Palatinate, Neuwied, Nassau, and Hesse (the duchy of Nassau and the electorate of Hesse having just been added to Prussia) met to come to an agreement, though confessing nonresistance as an article of the creed, ruled: "But how each congregation and each young man will indeed prove our old-Mennonite nonresistance, in order to satisfy his own conscience and the demands of the authorities, we leave to the judgment of each of them." This was the formula later often repeated to save the principle and at the same time abandon it.

The situation in Prussia proper was more fortunate. In the same year (1818) when at Hamburg Lieutenant Jansen sought in vain to return to his congregation in spite of his military service, the same thing happened to a David van Riesen of Elbing who had served in the Wars of Liberation and had nevertheless also tried to return to his congregation with the help of the courts. The emigration to Russia from 1788 on alleviated the economic difficulties (as the buying of property here was also limited) for those who remained. Besides, the "everlasting" privilege of 1780 gave a matchless support. But after 1848 the Mennonites of Prussia proper also had to realize the change of the times. There was the new Prussian constitution which proclaimed equal rights and equal duties for all (5 December 1848). At Frankfurt in August 1848 the Danzig members of the parliament (Martens and Osterrath) had in vain pleaded for the Mennonite privilege of nonresistance, pleading for tolerance. The West Prussian congregations met on 14 September 1848, at Heubuden and sent a petition to Frankfurt to recognize their convictions, but in vain. At Berlin in February 1849 delegates of the congregations met the Prime Minister of Brandenburg and at least obtained a postponement. But the discussions about the nonresistance of the Prussian Mennonites, their special tax and their limitations in buying new property continued. Peter Froese (d. 1853), elder of Orlofferfelde 1830-1853, wrote a pamphlet in 1850 once more defending nonresistance as an article of the Mennonite creed, and Wilhelm Mannhardt (1831-1880), the noted folklorist, in 1863 did the same by means of thorough historical research (Die Wehrfreiheit der Altpreussischen Mennoniten).

Even in 1867 the Prussian government proposed, in a bill concerning military service, exempting the members of those Mennonite and Quaker families who by laws or privileges were released from direct service, but obliging them to furnish an equivalent. Yet on 18 October 1867 the first Imperial Diet of the North German Confederation (the nucleus of the later German Empire) rejected this paragraph so that now all Mennonites had to serve in the army. Gerhard Penner (1805-1878), the elder of the Heubuden congregation 1852-1877, was informed of this vote the same day by wire. On the 23rd representatives of the Prussian congregations met in his house at Warnau (Koczelitzky) and a delegation of five set out at once for Berlin and on the 24th called on the Minister of War (Roon). Nevertheless the law was published on 9 November 1867. Summoned by the members of parliament of their region in February 1868 the five traveled to Berlin once more and for a whole week (18-26 February) called on the king and the crown prince, ministers and privy councilors, members of the parliament, etc. Most impressive was what the crown prince said; viz., that the whole royal house was trying to help them; he warned them against emigration to Russia and advised them at least to reserve a return for their children, as probably in Russia matters would soon turn the same way. In this very week, on 20 February, the ministers of War and of Interior in a common report recommended that the members of the older Mennonite families who were not willing to serve with arms might be trained as nurses, wagoners, etc., only. These proposals were sanctioned by the Order of Cabinet of the king on 3 March 1868. As a consequence of the new course the limitation as to property and the special tax on the Mennonites were rescinded.

The Prussian Mennonites reacted in several ways to these transactions and decisions. A smaller part emigrated to Russia (1853 f.) and to America (1873 f.). Those remaining were divided into a group which strongly clung to the Order of Cabinet, and another which was willing to serve with arms. The congregation of Montau-Gruppe was split into two for half a century on this question. In 1909-1914, of the 200 young Mennonites of Prussia proper in contact with their congregations nearly one half followed the Order of Cabinet, and the rest served with arms. In this respect for West and East Prussia World War I signified the end of nonresistance. In 1933 when the curatorium of the Vereinigung discussed the question of a new universal compulsory service nobody proposed asking for another "privilege." Even the confession of faith of the Mennonites in Prussia (1895), which forbade revenging oneself on one's neighbor, merely urged its members as far as possible to avoid the outrages of war. The German martyrs of nonresistance in World War II included only one Lutheran and many Jehovah's Witnesses, but no Mennonites. After the war American and Dutch Mennonite influences, as well as the impressions of the war, resulted in a new nonresistant trend. The new German constitution of 1950 made provision for alternative service for conscientious objectors.

As to the problem of the oath, regulations exempting Mennonites in the courts and as officials were made in Württemberg in 1807, in Bavaria in 1811, in Nassau in 1822, in the older provinces of Prussia in 1827, etc. Under Hitler it was rather easy to get such exemptions for soldiers in the army as early as 1935. But in certain other respects there was a long struggle, the oath being regarded by the National Socialists as a special foundation of the state; hence many had to render an oath, as the authorities ordered, even by radio, and many did so without scruples, although ultimately the requirement was waived for Mennonites.

As to public offices, for the 19th century at least two South German Mennonites may be named besides Hermann von Beckerath in the North, namely, Peter Eymann (1788-1855), a miller of Sembach (Palatinate), assistant preacher of his congregation, who was mayor of Frankenstein and in 1849 a Liberal member of the Bavarian parliament, and Jakob Finger (1825-1904), a lawyer of Monsheim (Hesse), in 1862-1865 a member of the Hessian parliament and in 1884-1898 minister of state. A look at the Mennonite Adressbuch of 1936 revealed all the difficulties of the question of office-holding in a modern state such as Germany. Mail, telegraph, and railways were managed by the state, and many schools and libraries also. But was working in them a public office in the sense of earlier times? And if we found a good many Mennonites in these offices, what about Mennonites in the administration of customs or in the revenue department? But then it was only a step to the courts and the police and then again only one more to serving as captain or admiral. At any rate, the principle of avoiding public offices was nearly forgotten. Sometimes and in some places (Berlin, Krefeld) there were Mennonites in an amazing number of public offices.

In 1874 a Prussian law allowed Mennonite congregations to incorporate. After 1924 Gustav Reimer (1884-1955) in a series of lawsuits liberated the Mennonites of Prussia proper (including the Free City of Danzig) from the obligation of paying taxes to the Protestant established church.

As to nonconformity nobody wanted to be very conspicuous, different, or shocking. At the end of the 19th century nonconformity was gradually dropped even by the Amish. On the other hand, even between the world wars, e.g., 1918-1939 in the Palatinate, it was a problem whether girls might be allowed to bob their hair. Sometime later even the older women had bobbed hair. Technical progress often did away with traditional fashions. Thus the world overcame nonconformity.

Foreign Influences

But also spiritual influences of the surrounding life helped to bring about change in the character of the Mennonite congregations in Germany. There was the Reveil in Holland in the early 19th century with its interest in missions and Bible distribution. Even in Krefeld in 1818-1834 the minister Isaac Molenaar (1776-1834), in close contact with Holland, was a spokesman of this renewal of Pietism. The English Baptist William Henry Angas (d. 1832) visited West Prussia in 1823 and the Palatinate in 1824 to make propaganda for the missions which the Baptists had started with William Carey in 1792. The Basel Mission (founded in 1815) in the South, the Berlin Mission (founded in 1824) in the North, and later (1847 ff.) the Mission of the Dutch Mennonites also were supported by the offerings of the German Mennonites. In the 1950s there was a German Mennonite Committee for Missions as a branch of an all-European Mennonite Mission Board. There was the "Gemeinschaftsbewegung" in the late 19th century with its Gospel songs which won the South more or less, in West Prussia particularly the Thiensdorf-Preussisch Rosengart congregation. Pietistic influences in general came especially from St. Chrischona (founded in 1840) and many similar schools. From 1858 on the Hahnsche Pietists of Württemberg with their universalism reached two congregations of Baden. As the Northwest German congregations (Lower Rhine and East Friesland) were in character like the Dutch congregations, quite different influences are found here. From the Netherlands and from the universities rationalism, liberalism, and modernism found their way into these congregations. Gustav Kraemer (1863-1948) in Krefeld (from 1903) and J. G. Appeldoorn (1862-1945) in Emden (1904-1916) were prominent representatives of these tendencies, the one coming from the German Protestant Church, the other from Holland, to which he later returned. A milder liberalism had appeared earlier in Prussia proper with Carl Harder (1820-1896), pastor at Neuwied 1857-1869 and at Elbing in the progressive town congregation 1869-1896, and with Hermann Gottlieb Mannhardt (1855-1927), pastor at Danzig from 1879. In general confessional boundaries became lax in certain areas. So we found non-Mennonite pastors of Mennonite congregations (Krefeld, Monsheim), and the opposite as well (Kiel).

The pietistic wing of the German Mennonites since 1857 was in constant contact with the Evangelical Alliance, represented for instance by Pastor H. van der Smissen of Hamburg. The South German Conference was represented at the World Conference for Faith and Order at Lausanne, Switzerland, in 1927 (Benjamin H. Unruh). The Vereinigung belonged officially after 1930 to the World Alliance for International Friendship through the Churches. In 1947-1948 the Vereinigung became a member of the World Council of Churches and one of the founders of the Committee of Christian Churches in Germany. In the World Council meeting at Amsterdam in 1948 it was represented (Ernst Crous and Otto Schowalter).