Difference between revisions of "Molotschna Mennonite Settlement (Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)"

| [unchecked revision] | [checked revision] |

GameoAdmin (talk | contribs) (CSV import - 20130820) |

m (Text replace - "<em>.</em>" to ".") |

||

| (3 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

__FORCETOC__ | __FORCETOC__ | ||

__TOC__ | __TOC__ | ||

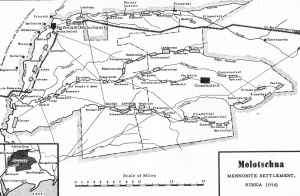

| − | [[File:ME3_733.jpg|300px|thumb|right|''Molotschna Mennonite settlement (map) in 1914. | + | [[File:ME3_733.jpg|300px|thumb|right|''Molotschna Mennonite settlement (map) in 1914. |

| − | Source: Mennonite Encyclopedia, v. 3, p. 733. | + | Source: Mennonite Encyclopedia, v. 3, p. 733.'']] <h3>Introduction</h3> The Molotschna Mennonite Settlement, located in the [[Taurida Guberniya (Ukraine)|province of Taurida]], Russia (now Zaporizhia Oblast in [[Ukraine|Ukraine]]), on the Molochnaya River, was the second and largest Mennonite settlement of [[Russia|Russia]]. [[Chortitza Mennonite Settlement (Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Chortitza]], founded in 1789, was the oldest and next in size. Chortitza was established by Mennonites of Danzig and Prussia who had followed the invitation of [[Catherine II, Empress of Russia (1729-1796)|Catherine the Great]] issued through her representative [[Trappe, George von (18th-19th century)|George von Trappe]]. The basis for this invitation was the fact that the Russian government needed good farmers in the [[Ukraine|Ukraine]] on land just acquired through a war with [[Turkey|Turkey]]. Land along the Vistula River in Prussia had become scarce and the Mennonite families were large; hence the Mennonites, who were by tradition farmers, were forced to seek other occupations, not all of which were open to Mennonites. Among the first settlers establishing the [[Chortitza Mennonite Settlement (Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Chortitza settlement]] were many artisans and laborers who longed to have their own farms. In 1787 [[Friedrich Wilhelm II, King of Prussia (1744-1797)|Friedrich Wilhelm II of Prussia]] issued an order of cabinet which forbade the Mennonites to enlarge their landholdings. The "Mennonite Edict" followed in 1789 with further restrictions. [[Friedrich Wilhelm III, King of Prussia (1770-1840)|Friedrich Wilhelm III]] further increased restrictions when he issued a declaration supplementary to the Mennonite Edict in 1801. All Mennonite efforts to have the edict changed were in vain. It became apparent that these restrictions were aimed to undermine the Mennonite principle of nonresistance. Mennonites who gave it up could purchase all the land they wanted. |

| − | |||

| − | '']] <h3>Introduction</h3> The Molotschna Mennonite Settlement, located in the [[Taurida Guberniya (Ukraine)|province of Taurida]], Russia (now Zaporizhia Oblast in [[Ukraine|Ukraine]]), on the Molochnaya River, was the second and largest Mennonite settlement of [[Russia|Russia]]. [[Chortitza Mennonite Settlement (Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Chortitza]], founded in 1789, was the oldest and next in size. Chortitza was established by Mennonites of Danzig and Prussia who had followed the invitation of [[Catherine II, Empress of Russia (1729-1796)|Catherine the Great]] issued through her representative [[Trappe, George von (18th-19th century)|George von Trappe]]. The basis for this invitation was the fact that the Russian government needed good farmers in the [[Ukraine|Ukraine]] on land just acquired through a war with [[Turkey|Turkey]]. Land along the Vistula River in Prussia had become scarce and the Mennonite families were large; hence the Mennonites, who were by tradition farmers, were forced to seek other occupations, not all of which were open to Mennonites. Among the first settlers establishing the [[Chortitza Mennonite Settlement (Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Chortitza settlement]] were many artisans and laborers who longed to have their own farms. In 1787 [[Friedrich Wilhelm II, King of Prussia (1744-1797)|Friedrich Wilhelm II of Prussia]] issued an order of cabinet which forbade the Mennonites to enlarge their landholdings. The "Mennonite Edict" followed in 1789 with further restrictions. [[Friedrich Wilhelm III, King of Prussia (1770-1840)|Friedrich Wilhelm III]] further increased restrictions when he issued a declaration supplementary to the Mennonite Edict in 1801. All Mennonite efforts to have the edict changed were in vain. It became apparent that these restrictions were aimed to undermine the Mennonite principle of nonresistance. Mennonites who gave it up could purchase all the land they wanted. | ||

<h3>Beginning</h3> In spite of the reports of hardships experienced by the [[Chortitza Mennonite Settlement (Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Chortitza]] settlers a new movement to the steppes of the [[Ukraine|Ukraine]] began in 1803. [[Warkentin, Cornelius (1740-1809)|Elder Cornelius Warkentin]] of Rosenort, who had been in Russia in 1798, was in correspondence with [[Kontenius, Samuel (1749-1830)|Kontenius]] and found out that there was land available for several thousand families on the Molochnaya east of the Dnieper. This was the major topic of discussion at the West Prussian Mennonite ministers' conference on 10 August 1803. Of particular significance was the special <em>[[Privileges (Privilegia)|Privilegium]] </em>which [[Paul I, Emperor of Russia (1754-1801)|Tsar Paul I]] had given the Mennonites in 1800. The first Molotschna group arrived at Chortitza in the fall of 1803 and continued its trip in the spring. Other groups followed, making a total of 365 families during 1803-1806. The immigrants were on the average much more prosperous than those who had gone to Chortitza. | <h3>Beginning</h3> In spite of the reports of hardships experienced by the [[Chortitza Mennonite Settlement (Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Chortitza]] settlers a new movement to the steppes of the [[Ukraine|Ukraine]] began in 1803. [[Warkentin, Cornelius (1740-1809)|Elder Cornelius Warkentin]] of Rosenort, who had been in Russia in 1798, was in correspondence with [[Kontenius, Samuel (1749-1830)|Kontenius]] and found out that there was land available for several thousand families on the Molochnaya east of the Dnieper. This was the major topic of discussion at the West Prussian Mennonite ministers' conference on 10 August 1803. Of particular significance was the special <em>[[Privileges (Privilegia)|Privilegium]] </em>which [[Paul I, Emperor of Russia (1754-1801)|Tsar Paul I]] had given the Mennonites in 1800. The first Molotschna group arrived at Chortitza in the fall of 1803 and continued its trip in the spring. Other groups followed, making a total of 365 families during 1803-1806. The immigrants were on the average much more prosperous than those who had gone to Chortitza. | ||

| Line 23: | Line 21: | ||

</td> </tr> </table> | </td> </tr> </table> | ||

| − | <h3>Economic Life</h3> Published information shows that the Mennonites who came to the Molotschna had been more prosperous in [[West Prussia|West Prussia]] on the average than the Chortitza settlers, and included a number of experienced and aggressive farmers. Also they could profit from the experiences of the Chortitza settlers, and the soil was good. [[Cornies, Johann (1789-1848)|Johann Cornies]] and the [[Agricultural Association (South Russia)|Agricultural Association]] headed by him did much to overcome the pioneer difficulties. Cornies successfully demonstrated on his estate which crops were most suitable for the steppes and introduced and constantly improved cattle, sheep, horses, etc. He introduced summer fallow and suitable grains for the steppes. His introduction of fruit trees and an afforestation program were of great consequences far beyond the Mennonite settlement. Through the support of the Guardians' Committee of the government his experience and experiments bore fruit even among the nomadic tribes of the neighborhood and the Russian population. | + | <h3>Economic Life</h3> Published information shows that the Mennonites who came to the Molotschna had been more prosperous in [[West Prussia|West Prussia ]] on the average than the Chortitza settlers, and included a number of experienced and aggressive farmers. Also they could profit from the experiences of the Chortitza settlers, and the soil was good. [[Cornies, Johann (1789-1848)|Johann Cornies]] and the [[Agricultural Association (South Russia)|Agricultural Association]] headed by him did much to overcome the pioneer difficulties. Cornies successfully demonstrated on his estate which crops were most suitable for the steppes and introduced and constantly improved cattle, sheep, horses, etc. He introduced summer fallow and suitable grains for the steppes. His introduction of fruit trees and an afforestation program were of great consequences far beyond the Mennonite settlement. Through the support of the Guardians' Committee of the government his experience and experiments bore fruit even among the nomadic tribes of the neighborhood and the Russian population. |

Alexander Petzholdt, who visited the Molotschna Mennonites in 1855, gave a very good description of the agricultural life at that time. Their machinery was comparatively primitive; they were raising mainly sheep, cattle, horses, silk, and grains, including summer wheat, rye, barley, and oats. He found that the Mennonites had planted 754 million fruit and shade trees (Petzholdt, 180). Industry was in its early stages, with a number of mills, silk factories, carpenter and smith shops, brick factories, oil presses, breweries, etc. The products were much in demand among the population outside Molotschna. Some 500 non-Mennonites found employment among the Mennonites at that time (p. 187). | Alexander Petzholdt, who visited the Molotschna Mennonites in 1855, gave a very good description of the agricultural life at that time. Their machinery was comparatively primitive; they were raising mainly sheep, cattle, horses, silk, and grains, including summer wheat, rye, barley, and oats. He found that the Mennonites had planted 754 million fruit and shade trees (Petzholdt, 180). Industry was in its early stages, with a number of mills, silk factories, carpenter and smith shops, brick factories, oil presses, breweries, etc. The products were much in demand among the population outside Molotschna. Some 500 non-Mennonites found employment among the Mennonites at that time (p. 187). | ||

| Line 45: | Line 43: | ||

According to the estimates for forestry service taxation, the property of the Molotschna settlement before [[World War (1914-1918)|World War I]] (1914) amounted to 51,600,000 rubles ($25,800,000), which was no doubt a low estimate. | According to the estimates for forestry service taxation, the property of the Molotschna settlement before [[World War (1914-1918)|World War I]] (1914) amounted to 51,600,000 rubles ($25,800,000), which was no doubt a low estimate. | ||

| − | The Mennonites of the Molotschna settlement, like most of the other Mennonites of Russia, lived in villages, which were administered by a <em>[[Schulze |Schulze]] </em>(mayor). The total settlement had an administration under the leadership of an <em>[[Oberschulze|Oberschulze]] </em>located at Halbstadt | + | The Mennonites of the Molotschna settlement, like most of the other Mennonites of Russia, lived in villages, which were administered by a <em>[[Schulze |Schulze]] </em>(mayor). The total settlement had an administration under the leadership of an <em>[[Oberschulze|Oberschulze]] </em>located at Halbstadt. In 1870 the settlement was divided into two administrative units (volost), [[Halbstadt (Molotschna Mennonite Settlement, Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Halbstadt]] and [[Gnadenfeld (Molotschna Mennonite settlement, Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Gnadenfeld]]. Halbstadt included 31 villages and two estates, while Gnadenfeld had 26 villages and one estate (see [[map (Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|map]]). In addition to these two, Ohrloff was also significant as a cultural center. The local administration <em>(obshestvo) </em>was subject to the district administration <em>(okrug), </em>which in turn was subject to the Guardians' Committee. |

The men who served as <em>Oberschulze</em> at [[Halbstadt (Molotschna Mennonite Settlement, Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Halbstadt]], Molotschna, were [[Wiens, Klaas Klaas (1768-1821)|Klaas Wiens]] 1804-1806, Johann Klassen 1806-1808 and 1812-1814, Gerhard Reimer 1809-1811, Peter Töws 1815-1820, Johann Klassen (Ohrloff) 1824-1826, Johann Klassen (Tiegerweide) 1827-1832, Johann Regier 1833-1841, Abraham Töws 1842-1847, [[Friesen, David (19th century)|David Friesen]] 1848-1864, Franz Dück 1865-1866, Abraham Driedger 1867, Kornelius Töws 1868-1872, Abraham Wiebe 1873-1878, Peter Dück 1879-1881, Klaas Enns 1882-1884, Johann Enns 1885-1888, Peter Neufeld 1889-1898, Franz Nickel 1899-1906, Dietrich Dyck 1906-1910. | The men who served as <em>Oberschulze</em> at [[Halbstadt (Molotschna Mennonite Settlement, Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Halbstadt]], Molotschna, were [[Wiens, Klaas Klaas (1768-1821)|Klaas Wiens]] 1804-1806, Johann Klassen 1806-1808 and 1812-1814, Gerhard Reimer 1809-1811, Peter Töws 1815-1820, Johann Klassen (Ohrloff) 1824-1826, Johann Klassen (Tiegerweide) 1827-1832, Johann Regier 1833-1841, Abraham Töws 1842-1847, [[Friesen, David (19th century)|David Friesen]] 1848-1864, Franz Dück 1865-1866, Abraham Driedger 1867, Kornelius Töws 1868-1872, Abraham Wiebe 1873-1878, Peter Dück 1879-1881, Klaas Enns 1882-1884, Johann Enns 1885-1888, Peter Neufeld 1889-1898, Franz Nickel 1899-1906, Dietrich Dyck 1906-1910. | ||

| Line 55: | Line 53: | ||

<h3> Cultural and Religious Life</h3> In the early days cultural and religious life was on a higher level in the Molotschna than in [[Chortitza Mennonite Settlement (Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Chortitza]]. This was probably due mostly to the fact that the Molotschna Mennonites had stayed in their home country ([[West Prussia|West Prussia]]) longer, had there undergone more influences in education and had more vital religious experiences because of contacts with [[Pietism|Pietistic]] groups, and were of a generally higher economic status. However, as settlers they had to overcome the same hardships and problems of pioneering as the Chortitza people. In the realm of education they had the advantage of having Johann Cornies as an outstanding pioneer. Teachers like [[Voth, Tobias (b. 1791)|T. Voth]], [[Heese, Heinrich (1787-1868)|H. Heese]], and [[Franz, Heinrich (1812-1889)|H. Franz]] paved the way to higher goals. In addition to an improved elementary educational system a [[Secondary Education|secondary educational]] system followed gradually with its Zentralschulen, Mädchenschulen, and teacher training and business schools (see [[Education Among the Mennonites in Russia|Education Among the Mennonites of Russia]]). The Molotschna Mennonites were also ahead of the other Mennonite settlements in Russia as well as in America in the realm of [[Hospitals, Clinics and Dispensaries|hospital]] and [[Deaconess|deaconess]] work. | <h3> Cultural and Religious Life</h3> In the early days cultural and religious life was on a higher level in the Molotschna than in [[Chortitza Mennonite Settlement (Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Chortitza]]. This was probably due mostly to the fact that the Molotschna Mennonites had stayed in their home country ([[West Prussia|West Prussia]]) longer, had there undergone more influences in education and had more vital religious experiences because of contacts with [[Pietism|Pietistic]] groups, and were of a generally higher economic status. However, as settlers they had to overcome the same hardships and problems of pioneering as the Chortitza people. In the realm of education they had the advantage of having Johann Cornies as an outstanding pioneer. Teachers like [[Voth, Tobias (b. 1791)|T. Voth]], [[Heese, Heinrich (1787-1868)|H. Heese]], and [[Franz, Heinrich (1812-1889)|H. Franz]] paved the way to higher goals. In addition to an improved elementary educational system a [[Secondary Education|secondary educational]] system followed gradually with its Zentralschulen, Mädchenschulen, and teacher training and business schools (see [[Education Among the Mennonites in Russia|Education Among the Mennonites of Russia]]). The Molotschna Mennonites were also ahead of the other Mennonite settlements in Russia as well as in America in the realm of [[Hospitals, Clinics and Dispensaries|hospital]] and [[Deaconess|deaconess]] work. | ||

| − | The Mennonites of the Molotschna settlement were mostly of the [[Flemish Mennonites|Flemish]] branch. Only the village of Rudnerweide was of the [[Frisian Mennonites|Frisian]] branch. In 1805 the first 18 villages were organized into one congregation, the [[Orloff Mennonite Church (Molotschna Mennonite Settlement, Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Ohrloff-Petershagen-Halbstadt Mennonite Church]], with [[Enns, Jakob (1768-1818)|Jakob Enns]] as elder. [[Reimer, Klaas (1770-1837)|Klaas Reimer]] separated from this group in 1814 and founded the [[Kleine Gemeinde|Kleine Gemeinde]]. Another separation occurred in 1823 which resulted in the organization of the [[Lichtenau-Petershagen Mennonite Church (Molotschna Mennonite Settlement, Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Lichtenau-Petershagen Church]] | + | The Mennonites of the Molotschna settlement were mostly of the [[Flemish Mennonites|Flemish]] branch. Only the village of Rudnerweide was of the [[Frisian Mennonites|Frisian]] branch. In 1805 the first 18 villages were organized into one congregation, the [[Orloff Mennonite Church (Molotschna Mennonite Settlement, Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Ohrloff-Petershagen-Halbstadt Mennonite Church]], with [[Enns, Jakob (1768-1818)|Jakob Enns]] as elder. [[Reimer, Klaas (1770-1837)|Klaas Reimer]] separated from this group in 1814 and founded the [[Kleine Gemeinde|Kleine Gemeinde]]. Another separation occurred in 1823 which resulted in the organization of the [[Lichtenau-Petershagen Mennonite Church (Molotschna Mennonite Settlement, Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Lichtenau-Petershagen Church]]. Later this congregation was subdivided into the [[Margenau-Alexanderwohl-Landskrone Mennonite Church (Molotschna Mennonite Settlement, Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Margenau-Schönsee]], [[Pordenau Mennonite Church (Molotschna Mennonite Settlement, Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Pordenau]], and [[Alexanderkrone Mennonite Church (Molotschna Mennonite Settlement, Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Alexanderkrone]] congregations. In addition to these the following congregations were organized among the settlers that came later: Rudnerweide in 1820, consisting of the [[Frisian Mennonites|Frisian]] Mennonites alone, Alexanderwohl in 1820, [[Gnadenfeld Mennonite Church (Gnadenfeld, Molotschna Mennonite settlement, Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Gnadenfeld]] in 1834, and Waldheim in 1836, which were all of the same Old Flemish or Groningen Flemish background. The latter two represented a conservatism which had been softened and awakened through [[Moravian Church|Moravian]] and Pietistic influences. In addition to these congregations there existed independent congregations in most of the daughter settlements of the Molotschna. |

[[Gnadenfeld (Molotschna Mennonite settlement, Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Gnadenfeld]] became the center of an active religious life, promoting better education and missions. [[Dirks, Heinrich (1842-1915)|Heinrich Dirks]] of Gnadenfeld was the first Mennonite missionary from outside Holland. It was in these circles that the Pietist Eduard Wüst found response and caused a revival. This revival was welcomed and promoted by men like Bernhard Harder, but also caused a break resulting in the founding of the [[Mennonite Brethren Church|Mennonite Brethren Church]] in 1860. However, the difference between these two groups was never as great in the Molotschna as in [[Chortitza Mennonite Settlement (Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Chortitza]]. Men like P. M. Friesen tried to combine the best characteristics and traditions of both, founding the "Allianz" group or [[Fellowship of Evangelical Bible Churches|Evangelical Mennonite Brethren]] in 1905. The Mennonite Brethren as well as the Friends of Jerusalem established settlements on the Kuban River in the [[Caucasus|Caucasus]]. In 1880 [[Peters, Hermann (1841-1928)|Hermann Peters]] led a group of Molotschna Mennonites to [[Asiatic Russia|Central Asia]], where they found like-minded chiliasts in the followers of [[Epp, Claas (1838-1913)|Claas Epp]]. As a whole the Molotschna Mennonites maintained a balanced and active program of Christianity that aimed to manifest itself in all areas of life. | [[Gnadenfeld (Molotschna Mennonite settlement, Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Gnadenfeld]] became the center of an active religious life, promoting better education and missions. [[Dirks, Heinrich (1842-1915)|Heinrich Dirks]] of Gnadenfeld was the first Mennonite missionary from outside Holland. It was in these circles that the Pietist Eduard Wüst found response and caused a revival. This revival was welcomed and promoted by men like Bernhard Harder, but also caused a break resulting in the founding of the [[Mennonite Brethren Church|Mennonite Brethren Church]] in 1860. However, the difference between these two groups was never as great in the Molotschna as in [[Chortitza Mennonite Settlement (Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Chortitza]]. Men like P. M. Friesen tried to combine the best characteristics and traditions of both, founding the "Allianz" group or [[Fellowship of Evangelical Bible Churches|Evangelical Mennonite Brethren]] in 1905. The Mennonite Brethren as well as the Friends of Jerusalem established settlements on the Kuban River in the [[Caucasus|Caucasus]]. In 1880 [[Peters, Hermann (1841-1928)|Hermann Peters]] led a group of Molotschna Mennonites to [[Asiatic Russia|Central Asia]], where they found like-minded chiliasts in the followers of [[Epp, Claas (1838-1913)|Claas Epp]]. As a whole the Molotschna Mennonites maintained a balanced and active program of Christianity that aimed to manifest itself in all areas of life. | ||

| Line 71: | Line 69: | ||

In 1937-1938 in the Molotschna, just as in the other Mennonite settlements, many hundreds of men were taken by night and exiled. Little was known about their fate in the 1950s. Numerous exclusively Russian villages were established among the Mennonite villages of the Molotschna settlement. When the war between Germany and Russia broke out in 1941 many of the Mennonite men and women had to dig trenches west of the Dnieper River. Some were taken prisoners of war there by the German army. During the early days of the German attack the Soviets sent all Mennonite men over 16 years of age eastward. When the German army approached the total remaining population was ordered to meet at the stations of Halbstadt, Stulnevo, Tokmak, Lichtenau, and Feodorovka on 1 October 1941. Those that came to Lichtenau and Feodorovka were loaded on freight trains and sent east. Those who came to the depots of Halbstadt, Tokmak, and Stulnevo waited for five days, when the German army overran the territory, so that none of these were sent eastward. As a result of this evacuation and deportation in the Molotschna some 20 of the Mennonite villages had no Mennonite population left when the German army approached in 1941. They were Altonau, [[Münsterberg (South Russia)|Münsterberg]], Blumenstein, Lichtenau, [[Lindenau (Molotschna Mennonite Settlement, Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Lindenau]], Ohrloff, Tiege, Blumenort, Rosenort, [[Kleefeld|Kleefeld]], Alexanderkrone, [[Lichtfelde (Molotschna Mennonite Settlement, Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Lichtfelde]], [[Neukirch (Molotschna Mennonite Settlement, Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Neukirch]], Friedensruh, Prangenau, Steinfeld, [[Elisabethtal (Molotschna Mennonite Settlement, Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Elisabethtal]], Schardau, Pastwa, and [[Grossweide (Molotschna Mennonite Settlement, Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Grossweide]]. In some other villages the population had shrunk to half its normal size. After the war information was received from many of those evacuated; seemingly most of them were settled in Kazakhstan, Siberia. Here their life was at first extremely hard. Many perished and many members of families were not yet been able to locate each other to reunite. During the 1950s conditions seemed to have improved. Even worship services were arranged for, at places. | In 1937-1938 in the Molotschna, just as in the other Mennonite settlements, many hundreds of men were taken by night and exiled. Little was known about their fate in the 1950s. Numerous exclusively Russian villages were established among the Mennonite villages of the Molotschna settlement. When the war between Germany and Russia broke out in 1941 many of the Mennonite men and women had to dig trenches west of the Dnieper River. Some were taken prisoners of war there by the German army. During the early days of the German attack the Soviets sent all Mennonite men over 16 years of age eastward. When the German army approached the total remaining population was ordered to meet at the stations of Halbstadt, Stulnevo, Tokmak, Lichtenau, and Feodorovka on 1 October 1941. Those that came to Lichtenau and Feodorovka were loaded on freight trains and sent east. Those who came to the depots of Halbstadt, Tokmak, and Stulnevo waited for five days, when the German army overran the territory, so that none of these were sent eastward. As a result of this evacuation and deportation in the Molotschna some 20 of the Mennonite villages had no Mennonite population left when the German army approached in 1941. They were Altonau, [[Münsterberg (South Russia)|Münsterberg]], Blumenstein, Lichtenau, [[Lindenau (Molotschna Mennonite Settlement, Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Lindenau]], Ohrloff, Tiege, Blumenort, Rosenort, [[Kleefeld|Kleefeld]], Alexanderkrone, [[Lichtfelde (Molotschna Mennonite Settlement, Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Lichtfelde]], [[Neukirch (Molotschna Mennonite Settlement, Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Neukirch]], Friedensruh, Prangenau, Steinfeld, [[Elisabethtal (Molotschna Mennonite Settlement, Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Elisabethtal]], Schardau, Pastwa, and [[Grossweide (Molotschna Mennonite Settlement, Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Grossweide]]. In some other villages the population had shrunk to half its normal size. After the war information was received from many of those evacuated; seemingly most of them were settled in Kazakhstan, Siberia. Here their life was at first extremely hard. Many perished and many members of families were not yet been able to locate each other to reunite. During the 1950s conditions seemed to have improved. Even worship services were arranged for, at places. | ||

| − | During the German occupation of the Molotschna the Mennonites who had remained in the area began to revive their former way of living in the realm of agriculture, religious life, and education. Gradually the Mennonites began to farm privately; ministers were elected, churches reopened, and religious instruction and baptismal services were held. All this was of short duration. In the fall of 1943, when the German army withdrew, the total remaining Molotschna Mennonite population also went westward by wagons to be settled in the Warthegau, their ancestral home along the Vistula River in western [[Poland|Poland]]. When the Red army invaded Germany in 1945, the newly resettled Mennonites fled westward with the local population. At the end of the war some of the refugees found themselves in the Russian zone of Germany. Most of them were forcibly repatriated. Even some of those who had escaped into the British, American, and French zones were seized and returned to Russia. It is estimated that some 35,000 Mennonites were evacuated from Russia to Germany in 1943, but only some 12,000 of them found their way to [[Canada|Canada]] and [[South America|South America]]; the rest were sent back to Russia. We can assume that of these 12,000 emigrants not more than half were from the Molotschna settlement. With the help of American Mennonite relief agencies they found new homes in South America and Canada. Little was known in the 1950s about the | + | During the German occupation of the Molotschna the Mennonites who had remained in the area began to revive their former way of living in the realm of agriculture, religious life, and education. Gradually the Mennonites began to farm privately; ministers were elected, churches reopened, and religious instruction and baptismal services were held. All this was of short duration. In the fall of 1943, when the German army withdrew, the total remaining Molotschna Mennonite population also went westward by wagons to be settled in the Warthegau, their ancestral home along the Vistula River in western [[Poland|Poland]]. When the Red army invaded Germany in 1945, the newly resettled Mennonites fled westward with the local population. At the end of the war some of the refugees found themselves in the Russian zone of Germany. Most of them were forcibly repatriated. Even some of those who had escaped into the British, American, and French zones were seized and returned to Russia. It is estimated that some 35,000 Mennonites were evacuated from Russia to Germany in 1943, but only some 12,000 of them found their way to [[Canada|Canada]] and [[South America|South America]]; the rest were sent back to Russia. We can assume that of these 12,000 emigrants not more than half were from the Molotschna settlement. With the help of American Mennonite relief agencies they found new homes in South America and Canada. Little was known in the 1950s about the fate of the 60 villages and hamlets which constituted the Molotschna settlement, one of the most prosperous undertakings in Mennonite history, except that their former Mennonite inhabitants have been scattered over Siberia, Central Asia, Canada, and South America. Correspondence received from Russia indicated that some Mennonite families either stayed in the Molotschna villages or returned after [[World War (1939-1945) - Soviet Union|World War II]]. If the report regarding the village of Liebenau was typical, there must have been a number of Mennonite families residing in the Molotschna villages in the 1950s. An eyewitness reported in 1957 that of the 53 original prewar buildings of Liebenau, only 8 still stood. Among the 15 families living in the village, there were some Mennonites, some of whom had intermarried with Russians. Liebenau and the neighboring Russian village of Ostriekovka together formed a collective farm. <em>(Menn. Rundschau, </em>July 10, 1957, p. 2.) Similar reports have come from other places in the Molotschna settlement. |

There were also indications of worship services attended by Mennonites in the Molotschna region; whether Baptist - sponsored or Mennonite was not known in the 1950s. Now that there is greater freedom of movement in Russia, people from Northern and Eastern Russia returned to visit their home community in the Molotschna. Whether nostalgia and newly won freedom would make it possible for greater numbers to return and to concentrate in some areas or villages remained to be seen. | There were also indications of worship services attended by Mennonites in the Molotschna region; whether Baptist - sponsored or Mennonite was not known in the 1950s. Now that there is greater freedom of movement in Russia, people from Northern and Eastern Russia returned to visit their home community in the Molotschna. Whether nostalgia and newly won freedom would make it possible for greater numbers to return and to concentrate in some areas or villages remained to be seen. | ||

| Line 89: | Line 87: | ||

Epp, David H. "Historische Uebersicht über den Zustand der Mennonitengemeinden an der Molotschna vom Jahre 1836." <em>Unser Blatt </em>3 (1928): 110-112, 138-143. | Epp, David H. "Historische Uebersicht über den Zustand der Mennonitengemeinden an der Molotschna vom Jahre 1836." <em>Unser Blatt </em>3 (1928): 110-112, 138-143. | ||

| − | Epp, David H. <em>Johann Cornies: Züge aus seinem Leben und Wirken. </em>Jekaterinoslaw ; Berdjansk : "Der Botschafter", 1909 | + | Epp, David H. <em>Johann Cornies: Züge aus seinem Leben und Wirken. </em>Jekaterinoslaw ; Berdjansk : "Der Botschafter", 1909. Reprinted Steinbach, MB, 1946. |

Epp, David H. <em>Johann Cornies. </em>Published jointly by CMBC Publications : Manitoba Mennonite Historical Society, 1995. | Epp, David H. <em>Johann Cornies. </em>Published jointly by CMBC Publications : Manitoba Mennonite Historical Society, 1995. | ||

Revision as of 20:40, 13 April 2014

Introduction

The Molotschna Mennonite Settlement, located in the province of Taurida, Russia (now Zaporizhia Oblast in Ukraine), on the Molochnaya River, was the second and largest Mennonite settlement of Russia. Chortitza, founded in 1789, was the oldest and next in size. Chortitza was established by Mennonites of Danzig and Prussia who had followed the invitation of Catherine the Great issued through her representative George von Trappe. The basis for this invitation was the fact that the Russian government needed good farmers in the Ukraine on land just acquired through a war with Turkey. Land along the Vistula River in Prussia had become scarce and the Mennonite families were large; hence the Mennonites, who were by tradition farmers, were forced to seek other occupations, not all of which were open to Mennonites. Among the first settlers establishing the Chortitza settlement were many artisans and laborers who longed to have their own farms. In 1787 Friedrich Wilhelm II of Prussia issued an order of cabinet which forbade the Mennonites to enlarge their landholdings. The "Mennonite Edict" followed in 1789 with further restrictions. Friedrich Wilhelm III further increased restrictions when he issued a declaration supplementary to the Mennonite Edict in 1801. All Mennonite efforts to have the edict changed were in vain. It became apparent that these restrictions were aimed to undermine the Mennonite principle of nonresistance. Mennonites who gave it up could purchase all the land they wanted.

Beginning

In spite of the reports of hardships experienced by the Chortitza settlers a new movement to the steppes of the Ukraine began in 1803. Elder Cornelius Warkentin of Rosenort, who had been in Russia in 1798, was in correspondence with Kontenius and found out that there was land available for several thousand families on the Molochnaya east of the Dnieper. This was the major topic of discussion at the West Prussian Mennonite ministers' conference on 10 August 1803. Of particular significance was the special Privilegium which Tsar Paul I had given the Mennonites in 1800. The first Molotschna group arrived at Chortitza in the fall of 1803 and continued its trip in the spring. Other groups followed, making a total of 365 families during 1803-1806. The immigrants were on the average much more prosperous than those who had gone to Chortitza.

Various things hindered the emigration movement. The German authorities kept 10 per cent of the property of those leaving the country. For a while passports were refused. Also the Napoleonic wars stopped the emigration for a time. In 1819-1820 again 254 families went to the Molotschna. More groups followed. In 1835 the migration to the Molotschna came to a close, with a total of 1,200 families (Unruh, 231) and an estimated population of 6,000. The land complex of the settlement consisted of 120,000 desiatinas (324,000 acres) located east of the Molochnaya River along its tributaries the Tokmak, Begemthsokrak, Kurushan, and Yushanlee, about 100 miles (165 km) southeast of the Chortitza settlement. To the west resided non-Mennonite German settlers, to the north and east Ukrainians, and to the south nomadic tribes. Around 1870 the Molotschna settlement consisted of the following villages, besides many large estates located within the boundary of the settlement.

Villages of the Molotschna Settlement in 1860 based on Isaac, Molotschnaer Mennoniten, pp. 72-73

(To sort the table click on a heading)

These are the names of the 60 Molotschna villages and hamlets with years when founded, number of "full farms" (175 acres), "half size farms," and individuals (landless) who had only a house and possibly a few acres of land (1860), and total acreage of each village.

| Village | Founded | Full Farms | Half Farms | Landless | Acreage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Halbstadt | 1804 | 21 | 28 | 5192 | |

| Neu-Halbstadt | 1804 | 39 | 2259 | ||

| Muntau | 1804 | 17 | 8 | 38 | 5327 |

| Schönau | 1804 | 19 | 4 | 24 | 4722 |

| Fischau | 1804 | 16 | 12 | 23 | 4854 |

| Lindenau | 1804 | 19 | 4 | 29 | 4938 |

| Lichtenau | 1804 | 18 | 6 | 26 | 4808 |

| Blumstein | 1804 | 20 | 2 | 51 | 5888 |

| Münsterberg | 1804 | 22 | 24 | 4997 | |

| Altona | 1804 | 21 | 2 | 31 | 5200 |

| Ladekopp | 1805 | 20 | 29 | 4762 | |

| Schönsee | 1805 | 19 | 2 | 26 | 4633 |

| Petershagen | 1805 | 17 | 6 | 19 | 4330 |

| Tiegenhagen | 1805 | 19 | 4 | 24 | 4822 |

| Ohrloff | 1805 | 21 | 26 | 4908 | |

| Tiege | 1805 | 20 | 23 | 4503 | |

| Blumenort | 1805 | 19 | 2 | 23 | 4503 |

| Rosenort | 1805 | 19 | 2 | 27 | 4776 |

| Fürstenau | 1806 | 20 | 2 | 37 | 5283 |

| Rückenau | 1811 | 14 | 12 | 34 | 4978 |

| Margenau | 1819 | 19 | 10 | 31 | 5551 |

| Lichtfelde | 1819 | 16 | 8 | 27 | 4876 |

| Neukirch | 1819 | 17 | 6 | 26 | 4633 |

| Alexandertal | 1820 | 15 | 12 | 26 | 4808 |

| Schardau | 1820 | 16 | 8 | 28 | 4719 |

| Pordenau | 1820 | 19 | 2 | 27 | 4676 |

| Mariental | 1820 | 17 | 6 | 36 | 5065 |

| Rudnerweide | 1820 | 28 | 10 | 46 | 7778 |

| Grossweide | 1820 | 21 | 6 | 31 | 5551 |

| Franztal | 1820 | 10 | 28 | 25 | 5251 |

| Pastwa | 1820 | 17 | 2 | 23 | 5292 |

| Fürstenwerder | 1821 | 18 | 4 | 33 | 4752 |

| Alexanderwohl | 1821 | 25 | 10 | 26 | 6691 |

| Gnadenheim | 1821 | 22 | 4 | 29 | 6388 |

| Tiegerweide | 1822 | 22 | 4 | 32 | 5465 |

| Liebenau | 1823 | 20 | 22 | 5594 | |

| Elisabethal | 1823 | 22 | 6 | 29 | 4460 |

| Wernersdorf | 1824 | 29 | 2 | 45 | 5640 |

| Friedensdorf | 1824 | 27 | 6 | 26 | 7209 |

| Prangenau | 1824 | 16 | 8 | 33 | 6388 |

| Sparrau | 1828 | 32 | 16 | 37 | 4936 |

| Konteniusfeld | 1832 | 25 | 10 | 33 | 8618 |

| Gnadenfeld | 1835 | 34 | 12 | 38 | 6691 |

| Waldheim | 1836 | 34 | 12 | 56 | 8862 |

| Landskrone | 1839 | 36 | 8 | 34 | 9439 |

| Hierschau | 1848 | 30 | 30 | 8489 | |

| Nikolaidorf | 1851 | 22 | 8 | 6561 | |

| Paulsheim | 1852 | 25 | 2 | 10 | 4207 |

| Kleefeld | 1854 | 37 | 6 | 38 | 4995 |

| Alexanderkrone | 1857 | 40 | 25 | 8662 | |

| Mariawohl | 1857 | 21 | 4 | 8100 | |

| Friedensruh | 1857 | 28 | 4 | 24 | 3838 |

| Steinfeld | 1857 | 29 | 2 | 6 | 6302 |

| Gnadental | 1862 | 30 | 9 | 5524 | |

| Hamberg | 1863 | 25 | 2 | 5 | 4779 |

| Klippenfeld | 1863 | 27 | 14 | 5343 | |

| Fabrikerwiese | 1863 | 3 | 10 | 959 | |

| Felsental | 1820 | ||||

| Yushanlee | 1811 | ||||

| Steinbach | 1812 |

Economic Life

Published information shows that the Mennonites who came to the Molotschna had been more prosperous in West Prussia on the average than the Chortitza settlers, and included a number of experienced and aggressive farmers. Also they could profit from the experiences of the Chortitza settlers, and the soil was good. Johann Cornies and the Agricultural Association headed by him did much to overcome the pioneer difficulties. Cornies successfully demonstrated on his estate which crops were most suitable for the steppes and introduced and constantly improved cattle, sheep, horses, etc. He introduced summer fallow and suitable grains for the steppes. His introduction of fruit trees and an afforestation program were of great consequences far beyond the Mennonite settlement. Through the support of the Guardians' Committee of the government his experience and experiments bore fruit even among the nomadic tribes of the neighborhood and the Russian population.

Alexander Petzholdt, who visited the Molotschna Mennonites in 1855, gave a very good description of the agricultural life at that time. Their machinery was comparatively primitive; they were raising mainly sheep, cattle, horses, silk, and grains, including summer wheat, rye, barley, and oats. He found that the Mennonites had planted 754 million fruit and shade trees (Petzholdt, 180). Industry was in its early stages, with a number of mills, silk factories, carpenter and smith shops, brick factories, oil presses, breweries, etc. The products were much in demand among the population outside Molotschna. Some 500 non-Mennonites found employment among the Mennonites at that time (p. 187).

Around 1850 great changes took place in the life of the Molotschna Mennonites. With the increase of the population, the improvement of agricultural machinery, and the introduction of the hard winter wheat, a more intensive farming came about. Winter wheat became the chief crop and as a result factories of agricultural machinery and a milling industry developed. In addition many branches of business were introduced. Favorable soil and climatic conditions, the industry of the majority of the farmers, and farsighted leadership made the Molotschna settlement a garden spot of the Ukraine and one of the most successful Mennonite settlements of Russia (see also Agriculture, Business). However, the settlement also had to solve a growing problem usually referred to as the landless question. The table "Villages of the Molotschna Settlement" gives a vivid picture of the land distribution. By 1860 the great majority of the population was landless. The number of families had increased rapidly, and parceling out a normal-sized farm (175 acres) was prohibited. The surplus population usually obtained some land to build little cottages at the end of the village and eked out a meager living as laborers or artisans. Unfortunately the landowners resisted all attempts to provide the landless with better opportunities to secure land or the right to vote. Since only the owners of farms had the right to vote, the landless were denied this right. Finally in 1866 the landless population had persuaded the Russian government to distribute the community surplus and reserve land, which had been rented out mostly to the well-to-do farmers. Each family thus received 16 desiatinas (some 40 acres) of land and with it the right to vote. By 1869 the land had been distributed among 1,563 families.

This was, however, only a partial and temporary solution of a continuously increasing problem. Gradually a colonization system was developed by which the surplus population was given the opportunity to establish their own homes on new settlements called daughter colonies or settlements. The administration of the mother settlement created funds for the purchase of new lands, and supervised the purchase, the financing, and the distribution of the land. Most of the daughter settlements originated on this basis, although some smaller settlements were started through private initiative. The following are the names of the most important settlements or the areas in which they were located; many scattered villages and estates are not mentioned. It is worthy of note that the Chortitza settlement had established daughter settlements much earlier, the first in 1836 at Bergthal. But the Molotschna established more settlements than Chortitza in 1862-1901.

Molotschna Daughter Settlements

(To sort the table click on a heading)

| Name | Province | Year Established | Number of Villages | Acreage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crimea | Taurida | 1862 | 25 | 108,000 |

| Kuban | Kuban district | 1863 | 2 | 17,550 |

| Brazol (Schönfeld) | Ekaterinoslav | 1868 | 4 | 150,000 |

| Zagradovka | Kherson | 1871 | 16 | 56,130 |

| Auli Ata | Turkestan | 1880 | 4 | 9,450 |

| Memrik | Ekaterinoslav | 1885 | 10 | 32,400 |

| Neu-Samara | Samara | 1890 | 12 | 59,400 |

| Davlekanovo | Ufa | 1894 | scattered | — |

| Orenburg | Orenburg | 1894 | 8 | 29,700 |

| Suvorovka | Stavropol | 1894 | 4 | 10,800 |

| Olgino | Olgino | 1895 | 2 | 11,920 |

| Terek | Caucasus | 1901 | 15 | 76,960 |

In addition to this, Molotschna Mennonites purchased in their neighborhood and in various other provinces smaller and larger estates. Also they established places of business and industries. The largest and best-known estates were those of Johann Cornies at Yushanlee and Tashchenak; Brodsky near Melitopol, Crimea; and Apanlee.

In the large Mennonite settlements in Siberia many villages were established by Molotschna settlers. They had over 100 villages with an acreage of over one million.

According to the estimates for forestry service taxation, the property of the Molotschna settlement before World War I (1914) amounted to 51,600,000 rubles ($25,800,000), which was no doubt a low estimate.

The Mennonites of the Molotschna settlement, like most of the other Mennonites of Russia, lived in villages, which were administered by a Schulze (mayor). The total settlement had an administration under the leadership of an Oberschulze located at Halbstadt. In 1870 the settlement was divided into two administrative units (volost), Halbstadt and Gnadenfeld. Halbstadt included 31 villages and two estates, while Gnadenfeld had 26 villages and one estate (see map). In addition to these two, Ohrloff was also significant as a cultural center. The local administration (obshestvo) was subject to the district administration (okrug), which in turn was subject to the Guardians' Committee.

The men who served as Oberschulze at Halbstadt, Molotschna, were Klaas Wiens 1804-1806, Johann Klassen 1806-1808 and 1812-1814, Gerhard Reimer 1809-1811, Peter Töws 1815-1820, Johann Klassen (Ohrloff) 1824-1826, Johann Klassen (Tiegerweide) 1827-1832, Johann Regier 1833-1841, Abraham Töws 1842-1847, David Friesen 1848-1864, Franz Dück 1865-1866, Abraham Driedger 1867, Kornelius Töws 1868-1872, Abraham Wiebe 1873-1878, Peter Dück 1879-1881, Klaas Enns 1882-1884, Johann Enns 1885-1888, Peter Neufeld 1889-1898, Franz Nickel 1899-1906, Dietrich Dyck 1906-1910.

When Gnadenfeld became an independent volost the following served as Oberschulze: Wilhelm Ewert 1870, Franz Penner 1871, Peter Ewert 1872-1875 and 1877-1878, Gerhard Fast 1876, David Unruh 1878-1887, Gerhard Dürksen 1887-1904, and Jacob Dürksen 1904-1910.

Molotschna had a mutual fire insurance agency and a Waisenamt, which took care of the orphans of the settlement and regulated inheritance.

Cultural and Religious Life

In the early days cultural and religious life was on a higher level in the Molotschna than in Chortitza. This was probably due mostly to the fact that the Molotschna Mennonites had stayed in their home country (West Prussia) longer, had there undergone more influences in education and had more vital religious experiences because of contacts with Pietistic groups, and were of a generally higher economic status. However, as settlers they had to overcome the same hardships and problems of pioneering as the Chortitza people. In the realm of education they had the advantage of having Johann Cornies as an outstanding pioneer. Teachers like T. Voth, H. Heese, and H. Franz paved the way to higher goals. In addition to an improved elementary educational system a secondary educational system followed gradually with its Zentralschulen, Mädchenschulen, and teacher training and business schools (see Education Among the Mennonites of Russia). The Molotschna Mennonites were also ahead of the other Mennonite settlements in Russia as well as in America in the realm of hospital and deaconess work.

The Mennonites of the Molotschna settlement were mostly of the Flemish branch. Only the village of Rudnerweide was of the Frisian branch. In 1805 the first 18 villages were organized into one congregation, the Ohrloff-Petershagen-Halbstadt Mennonite Church, with Jakob Enns as elder. Klaas Reimer separated from this group in 1814 and founded the Kleine Gemeinde. Another separation occurred in 1823 which resulted in the organization of the Lichtenau-Petershagen Church. Later this congregation was subdivided into the Margenau-Schönsee, Pordenau, and Alexanderkrone congregations. In addition to these the following congregations were organized among the settlers that came later: Rudnerweide in 1820, consisting of the Frisian Mennonites alone, Alexanderwohl in 1820, Gnadenfeld in 1834, and Waldheim in 1836, which were all of the same Old Flemish or Groningen Flemish background. The latter two represented a conservatism which had been softened and awakened through Moravian and Pietistic influences. In addition to these congregations there existed independent congregations in most of the daughter settlements of the Molotschna.

Gnadenfeld became the center of an active religious life, promoting better education and missions. Heinrich Dirks of Gnadenfeld was the first Mennonite missionary from outside Holland. It was in these circles that the Pietist Eduard Wüst found response and caused a revival. This revival was welcomed and promoted by men like Bernhard Harder, but also caused a break resulting in the founding of the Mennonite Brethren Church in 1860. However, the difference between these two groups was never as great in the Molotschna as in Chortitza. Men like P. M. Friesen tried to combine the best characteristics and traditions of both, founding the "Allianz" group or Evangelical Mennonite Brethren in 1905. The Mennonite Brethren as well as the Friends of Jerusalem established settlements on the Kuban River in the Caucasus. In 1880 Hermann Peters led a group of Molotschna Mennonites to Central Asia, where they found like-minded chiliasts in the followers of Claas Epp. As a whole the Molotschna Mennonites maintained a balanced and active program of Christianity that aimed to manifest itself in all areas of life.

When the Mennonites of Russia in the 1870's had to accept state service, the Mennonites of the Molotschna led in the negotiations with the government and also in the emigration to America. The Molotschna Mennonites went mostly to the United States, while the Chortitza Mennonites and their daughter settlements preferred Canada. Of the total of some 18,000, half must have come from the Molotschna. The passenger lists available in the 1950s had not yet been investigated as to where the immigrants came from. Those that stayed accepted forestry service and later also hospital work.

In 1905 the Molotschna settlement had the following congregations (the figures in parentheses indicate the year of founding and the total membership including children): Halbstadt (1895; 1174), Lichtenau (1823; 3338), Petershagen (?; 722), Schönfeld and branches (1868 ft; 763), Blumenfeld (1872; 135), Rosenhof (1870; 419), Ohrloff (1804; 980), Herzenberg (1881; 80), Alexanderkrone (1890; 1305), Neukirch (1863; 890), Alexanderwohl (1820; 680), Schönsee (1830; 1425), Gnadenfeld (and branches) (1834 ff.; 1151), Pordenau (1842; 1771), Rudnerweide (1820; 2548), Margenau (1832; 2876), Waldheim (1836; 219). The Mennonite Brethren were organized as the Rückenau Mennonite Brethren Church, with a number of branches (1860; 1977).

In 1926 the total membership (including children) of the combined Mennonite congregations in the Molotschna was 15,036, of the Mennonite Brethren 2,501, and the Evangelical Mennonite Brethren 810, a total of 17,347. Another source says there were 20,706 Mennonites in the Molotschna settlement in 1922. Taking into consideration the natural increase it may be concluded that some 4,000 must have emigrated to America in 1922-1926.

After World War I

World War I had the same effect on the Molotschna settlement as on the other settlements in Russia. The suffering inflicted by the Bolshevik Revolution, the bandits of Makhno, the civil war, drought, and starvation was gradually overcome, partly through American Mennonite relief. According to a report entitled "American Mennonite Relief Scheme" there was a population of 20,706 in the Molotschna in 1922, of whom 11,134 received relief food. The Association of Citizens of Dutch Origin (Verband Burger hollandischer Herkunft) did much to prevent great disaster, and to help to restore the economic, cultural, and religious life. The NEP period made this restoration possible. Soon, however, the great Mennonite emigration to Canada set in (1921), which was discontinued by 1927. Again in 1929 a small number succeeded in leaving Russia for Canada. How many of the 25,000 emigrants from Russia who went to North America after World War I came from the Molotschna has never been established.

In 1930 the collectivization and the deportation of "kulaks" to the slave labor camps began. Most of the churches were closed and ministers exiled. The meetinghouses were turned into club houses, nurseries, schools, granaries, etc. All schools became state schools with a Communistic curriculum and philosophy of life. The Mennonite teachers either had to adjust themselves or be exiled.

In 1937-1938 in the Molotschna, just as in the other Mennonite settlements, many hundreds of men were taken by night and exiled. Little was known about their fate in the 1950s. Numerous exclusively Russian villages were established among the Mennonite villages of the Molotschna settlement. When the war between Germany and Russia broke out in 1941 many of the Mennonite men and women had to dig trenches west of the Dnieper River. Some were taken prisoners of war there by the German army. During the early days of the German attack the Soviets sent all Mennonite men over 16 years of age eastward. When the German army approached the total remaining population was ordered to meet at the stations of Halbstadt, Stulnevo, Tokmak, Lichtenau, and Feodorovka on 1 October 1941. Those that came to Lichtenau and Feodorovka were loaded on freight trains and sent east. Those who came to the depots of Halbstadt, Tokmak, and Stulnevo waited for five days, when the German army overran the territory, so that none of these were sent eastward. As a result of this evacuation and deportation in the Molotschna some 20 of the Mennonite villages had no Mennonite population left when the German army approached in 1941. They were Altonau, Münsterberg, Blumenstein, Lichtenau, Lindenau, Ohrloff, Tiege, Blumenort, Rosenort, Kleefeld, Alexanderkrone, Lichtfelde, Neukirch, Friedensruh, Prangenau, Steinfeld, Elisabethtal, Schardau, Pastwa, and Grossweide. In some other villages the population had shrunk to half its normal size. After the war information was received from many of those evacuated; seemingly most of them were settled in Kazakhstan, Siberia. Here their life was at first extremely hard. Many perished and many members of families were not yet been able to locate each other to reunite. During the 1950s conditions seemed to have improved. Even worship services were arranged for, at places.

During the German occupation of the Molotschna the Mennonites who had remained in the area began to revive their former way of living in the realm of agriculture, religious life, and education. Gradually the Mennonites began to farm privately; ministers were elected, churches reopened, and religious instruction and baptismal services were held. All this was of short duration. In the fall of 1943, when the German army withdrew, the total remaining Molotschna Mennonite population also went westward by wagons to be settled in the Warthegau, their ancestral home along the Vistula River in western Poland. When the Red army invaded Germany in 1945, the newly resettled Mennonites fled westward with the local population. At the end of the war some of the refugees found themselves in the Russian zone of Germany. Most of them were forcibly repatriated. Even some of those who had escaped into the British, American, and French zones were seized and returned to Russia. It is estimated that some 35,000 Mennonites were evacuated from Russia to Germany in 1943, but only some 12,000 of them found their way to Canada and South America; the rest were sent back to Russia. We can assume that of these 12,000 emigrants not more than half were from the Molotschna settlement. With the help of American Mennonite relief agencies they found new homes in South America and Canada. Little was known in the 1950s about the fate of the 60 villages and hamlets which constituted the Molotschna settlement, one of the most prosperous undertakings in Mennonite history, except that their former Mennonite inhabitants have been scattered over Siberia, Central Asia, Canada, and South America. Correspondence received from Russia indicated that some Mennonite families either stayed in the Molotschna villages or returned after World War II. If the report regarding the village of Liebenau was typical, there must have been a number of Mennonite families residing in the Molotschna villages in the 1950s. An eyewitness reported in 1957 that of the 53 original prewar buildings of Liebenau, only 8 still stood. Among the 15 families living in the village, there were some Mennonites, some of whom had intermarried with Russians. Liebenau and the neighboring Russian village of Ostriekovka together formed a collective farm. (Menn. Rundschau, July 10, 1957, p. 2.) Similar reports have come from other places in the Molotschna settlement.

There were also indications of worship services attended by Mennonites in the Molotschna region; whether Baptist - sponsored or Mennonite was not known in the 1950s. Now that there is greater freedom of movement in Russia, people from Northern and Eastern Russia returned to visit their home community in the Molotschna. Whether nostalgia and newly won freedom would make it possible for greater numbers to return and to concentrate in some areas or villages remained to be seen.

See also Russia, Ukraine, and articles under churches and institutions referred in this article.

Bibliography

"Aus vergilbten Papieren." Unser Blatt 1 (1926): 171 f.

Bondar', S. D., Sekta mennonitov v Rossii. Petrograd : Tipografiia, V.D. Smirnova, 1916.

Dirks, H. Mennonitisches Jahrbuch (1903-1913)

Dirks, Heinrich. Statistik der Mennonitengemeinden in Russland Ende 1905 : Anhang zum Mennonitischem Jahrbuche 1904/5. Gnadenfeld : [H. Dirks], 1906.

Ehrt, Adolf. Das Mennonitentum in Russland von seiner Einwanderung bis zur Gegenwart. Langensalza : Julius Beltz, 1932.

Epp, David H. "Historische Uebersicht über den Zustand der Mennonitengemeinden an der Molotschna vom Jahre 1836." Unser Blatt 3 (1928): 110-112, 138-143.

Epp, David H. Johann Cornies: Züge aus seinem Leben und Wirken. Jekaterinoslaw ; Berdjansk : "Der Botschafter", 1909. Reprinted Steinbach, MB, 1946.

Epp, David H. Johann Cornies. Published jointly by CMBC Publications : Manitoba Mennonite Historical Society, 1995.

Epp, Hermann. "From the Vistula to the Dnieper." Mennonite Life 6 (October 1951): 14 ff.

Fast, Gerhard. "The Mennonites under Stalin and Hitler." Mennonite Life 2 (April 1947): 18 ff.

Friesen, Peter M. The Mennonite Brotherhood in Russia (1789-1910), trans. J. B. Toews and others. Fresno, CA: Board of Christian Literature [M.B.], 1978, rev. ed. 1980

Friesen, Peter M. Die Alt-Evangelische Mennonitische Brüderschaft in Russland (1789-1910) im Rahmen der mennonitischen Gesamtgeschichte. Halbstadt: Verlagsgesellschaft "Raduga", 1911.

Goerz, H. The Molotschna settlement.Winnipeg, MB : Published jointly by CMBC Publications, Manitoba Mennonite Historical Society, 1993.

Goerz, H. Die Molotschnaer Ansiedlung: Entstehung, Entwicklung und Untergang. Steinbach, MB : Echo-Verlag, 1951.

Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. Mennonitisches Lexikon, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. III, 154-158.

Hylkema, Tjeerd Oeds.Die Mennoniten-Gemeinden in Russland während der Kriegs- und Revolutionsjahre 1914 bis 1920. Heilbronn a. Neckar : Kommissions-Verlag der Mennon. Flüchtlingsfürsorge, 1921.

Isaac, Franz.Die Molotschnaer Mennoniten: ein Beitrag zur Geschichte derselben: aus Akten älterer und neuerer Zeit, wie auch auf Grund eigener Erlebnisse und Erfahrungen dargestellt. Halbstadt, Taurien : H.J. Braun, 1908.

Klaus, A. Unsere Kolonien: Studien und Materialien zur Geschichte und Statistik der ausländischen Kolonisation in Russland. Odessa : Verlag der "Odessaer Zeitung", 1887.

Krahn, Cornelius, ed. From the steppes to the prairies (1874-1949) Newton, KS : Mennonite Publication Office, 1949.

Neufeld, J. "Die Flucht, 1943-46." Mennonite Life 6 (January 1951): 8 ff.

Petzholdt, Alexander. Reise im westlichen und südlichen europäischen Russland im Jahre 1855. Leipzig : H. Fries, 1864.

Quiring, Horst. "Die Auswanderung der Mennoniten aus Preussen 1788-1870." Mennonite Life 6 (April 1951): 37 ff.

Quiring, Jacob. Die Mundart von Chortitza in Süd-Russland: Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der philosophischen Fakultat (1. Sekt.) der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität zu München. München : Druckerei Studentenhaus München, Universität, 1928.

Rempel, David G. "The Mennonite colonies in New Russia: a study of their settlement and economic development from 1789 to 1914." PhD. diss., Stanford University, California, 1933.

"Statistik . . . " Unser Blatt 2 (1926): 51.

Unruh, Benjamin H. Die niederländisch-niederdeutschen Hintergründe der mennonitischen Ostwanderungen im 16., 18. und 19. Jahrhundert. Karlsruhe-Rüppurr: Selbstverlag, 1955.

| Author(s) | Cornelius Krahn |

|---|---|

| Date Published | 1957 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Krahn, Cornelius. "Molotschna Mennonite Settlement (Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1957. Web. 16 Apr 2024. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Molotschna_Mennonite_Settlement_(Zaporizhia_Oblast,_Ukraine)&oldid=120772.

APA style

Krahn, Cornelius. (1957). Molotschna Mennonite Settlement (Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 16 April 2024, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Molotschna_Mennonite_Settlement_(Zaporizhia_Oblast,_Ukraine)&oldid=120772.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 3, pp. 732-737. All rights reserved.

©1996-2024 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.