Difference between revisions of "Political Attitudes"

| [unchecked revision] | [checked revision] |

GameoAdmin (talk | contribs) (CSV import - 20130816) |

m (Added hyperlink.) |

||

| (5 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | Mennonite attitudes toward political parties and authorities have differed widely among the many groups in the Mennonite mosaic and within the more than 50 countries to which Mennonites have scattered. Mennonite attitudes have reflected both the [[Anabaptism|Anabaptist]] teaching that governments are ordained by God to maintain order and the teaching that government [[Authority|authority]] is limited and not to be obeyed when it contradicts the will of God ([[Civil Disobedience|civil disobedience]]). Modern warfare and the Mennonite refusal of military service have provided the focus for the shaping of Mennonite attitudes in the modern era of nationalism and militarism. | |

Mennonites generally have not shown a preference for either liberal or authoritarian systems, but have honored any government which offered them toleration and autonomy. Thus Mennonites gave their deference and appreciation to the tsars of [[Russia|Russia]], to the dictator Alfredo Stroessner of [[Paraguay|Paraguay]], but also to the liberal democracies of the [[United States of America|United States]] and [[Canada|Canada]] and to the "secular state" program of the Congress Party in [[India|India]]. The severe suffering of Mennonites under Russian Communism produced a strong anti-Communist sentiment, especially among emigrés from Russia. In the 1930s some Mennonites in Canada and [[Paraguay|Paraguay]] expressed sympathies for the anti-Communist stance of National Socialism in [[Germany|Germany]]. | Mennonites generally have not shown a preference for either liberal or authoritarian systems, but have honored any government which offered them toleration and autonomy. Thus Mennonites gave their deference and appreciation to the tsars of [[Russia|Russia]], to the dictator Alfredo Stroessner of [[Paraguay|Paraguay]], but also to the liberal democracies of the [[United States of America|United States]] and [[Canada|Canada]] and to the "secular state" program of the Congress Party in [[India|India]]. The severe suffering of Mennonites under Russian Communism produced a strong anti-Communist sentiment, especially among emigrés from Russia. In the 1930s some Mennonites in Canada and [[Paraguay|Paraguay]] expressed sympathies for the anti-Communist stance of National Socialism in [[Germany|Germany]]. | ||

| − | Modern democratic theory and practice have changed the context of Mennonite political attitudes and behavior. In the 17th and 19th centuries in Europe, Mennonites had the status of subjects with personal obligations to rulers or princes. In this relationship Mennonites often traded special [[Taxes|taxes]] for toleration. In modern democratic states which claim to derive authority from the people, Mennonites have had the status of citizens who are responsible for the civic order. The earliest Mennonite experience with democratic pluralism was in America. Historian Richard MacMaster has shown (MEA 1), contrary to earlier opinions, that Mennonites in colonial [[Pennsylvania (USA)|Pennsylvania]] voted in elections and gave support to the ruling pacifist Quaker party which protected their interests. The American War for independence (1775-83), in which the willingness to bear arms and swear a loyalty oath became tests of citizenship, removed Mennonites from political participation and made them "more than ever a people apart." American Mennonite immigrants of Swiss background maintained a stricter two-kingdom dualism and separation from politics than did the Dutch-Russian immigrants of the 1870s and 1880s in America. Some American Mennonites became active in state and national politics, but they needed to drift away from their Mennonite connections. [[Old Order Mennonites|Old Order Mennonites]], Old Order | + | Modern democratic theory and practice have changed the context of Mennonite political attitudes and behavior. In the 17th and 19th centuries in Europe, Mennonites had the status of subjects with personal obligations to rulers or princes. In this relationship Mennonites often traded special [[Taxes|taxes]] for toleration. In modern democratic states which claim to derive authority from the people, Mennonites have had the status of citizens who are responsible for the civic order. The earliest Mennonite experience with democratic pluralism was in America. Historian Richard MacMaster has shown (MEA 1), contrary to earlier opinions, that Mennonites in colonial [[Pennsylvania (USA)|Pennsylvania]] voted in elections and gave support to the ruling pacifist Quaker party which protected their interests. The American War for independence (1775-83), in which the willingness to bear arms and swear a loyalty oath became tests of citizenship, removed Mennonites from political participation and made them "more than ever a people apart." American Mennonite immigrants of Swiss background maintained a stricter two-kingdom dualism and separation from politics than did the Dutch-Russian immigrants of the 1870s and 1880s in America. Some American Mennonites became active in state and national politics, but they needed to drift away from their Mennonite connections. [[Old Order Mennonites|Old Order Mennonites]], [[Old Order Amish]], and other traditionalist groups have attempted a strict separation from political participation. |

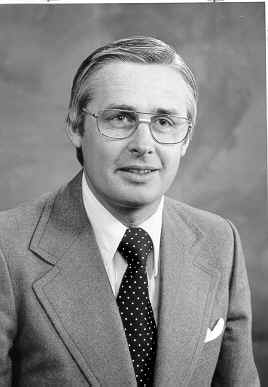

| + | [[File:EppJake.jpg|300px|thumb|right|''Jake Epp, Canadian MP and cabinet member in the 1980s'']] | ||

Mennonites who have an official or unofficial stance of political non-involvement often do have political preferences. Some theologically conservative Mennonites influenced by dispensationalist teachings have been keenly interested in contemporary events, often relating to the State of [[Israel|Israel]], which are said to reveal God's plan for the fulfillment of history. A study of the political socialization of "Old" Mennonite (MC) secondary school students (Leatherman, 1960) showed that Mennonites, compared to an American norm, were distinctively non-involved in partisan political activity but that they also reported unusually high identification with the Republican Party (70 percent). According to this study, historical factors which fostered the Republican preference included Mennonite opposition to slavery and to the Democrat South's Civil War rebellion against the national government (American Civil War), a positive response to generous Republican land policies on the frontier, and the concentration of Mennonite settlements in strongly Republican states. | Mennonites who have an official or unofficial stance of political non-involvement often do have political preferences. Some theologically conservative Mennonites influenced by dispensationalist teachings have been keenly interested in contemporary events, often relating to the State of [[Israel|Israel]], which are said to reveal God's plan for the fulfillment of history. A study of the political socialization of "Old" Mennonite (MC) secondary school students (Leatherman, 1960) showed that Mennonites, compared to an American norm, were distinctively non-involved in partisan political activity but that they also reported unusually high identification with the Republican Party (70 percent). According to this study, historical factors which fostered the Republican preference included Mennonite opposition to slavery and to the Democrat South's Civil War rebellion against the national government (American Civil War), a positive response to generous Republican land policies on the frontier, and the concentration of Mennonite settlements in strongly Republican states. | ||

| Line 9: | Line 10: | ||

In a sociological study of five Mennonite and Brethren in Christ groups in the United States and Canada in 1972 (Kaufman/Harder, 1975), 76 percent of the respondents said that church members should vote in public elections. Of those who expressed a party preference, three-fourths of the American Mennonites identified with the Republican Party. In Canada the party preferences were more evenly divided: 40 percent Conservative, 32 percent Liberal, 20 percent Social Credit. A historical study of the political [[Acculturation|acculturation]] of [[Kansas (USA)|Kansas]] Mennonites (Juhnke, 1975) showed that the distinctiveness of Mennonite party preferences changed over time. Until 1940 Kansas Mennonites (mostly General Conference and of Dutch-Russian background) scattered their votes among the political parties in about the same percentages as their non-Mennonite neighbors. There was substantial variation among congregations, however. The Swiss-Volyhnians were less strongly Republican than were the Dutch-Russian Alexanderwohlers. In the 1940 election, when it was clear that President Franklin D. Roosevelt was leading the country into war, the Kansas Mennonites voted in Republican majorities which were distinctively larger than their non-Mennonite neighbors. The Democrat party was identified with war, as it had been in the Civil War and again in World War I. Issues of war and peace affected American Mennonite political attitudes and behavior more than did issues of social welfare, although Mennonites voted in especially large numbers in which "moral issues" such as Prohibition or [[Capital Punishment|capital punishment]] were at stake. | In a sociological study of five Mennonite and Brethren in Christ groups in the United States and Canada in 1972 (Kaufman/Harder, 1975), 76 percent of the respondents said that church members should vote in public elections. Of those who expressed a party preference, three-fourths of the American Mennonites identified with the Republican Party. In Canada the party preferences were more evenly divided: 40 percent Conservative, 32 percent Liberal, 20 percent Social Credit. A historical study of the political [[Acculturation|acculturation]] of [[Kansas (USA)|Kansas]] Mennonites (Juhnke, 1975) showed that the distinctiveness of Mennonite party preferences changed over time. Until 1940 Kansas Mennonites (mostly General Conference and of Dutch-Russian background) scattered their votes among the political parties in about the same percentages as their non-Mennonite neighbors. There was substantial variation among congregations, however. The Swiss-Volyhnians were less strongly Republican than were the Dutch-Russian Alexanderwohlers. In the 1940 election, when it was clear that President Franklin D. Roosevelt was leading the country into war, the Kansas Mennonites voted in Republican majorities which were distinctively larger than their non-Mennonite neighbors. The Democrat party was identified with war, as it had been in the Civil War and again in World War I. Issues of war and peace affected American Mennonite political attitudes and behavior more than did issues of social welfare, although Mennonites voted in especially large numbers in which "moral issues" such as Prohibition or [[Capital Punishment|capital punishment]] were at stake. | ||

| − | + | Since World War II Mennonites in the five western provinces of Canada became more extensively involved as voters and as officeholders in provincial and national politics than Mennonites have ever been anywhere. In recent elections from 3-10 Mennonites have stood for provincial offices while 15 or more have been nominated for national offices. In 1979-80 Jake Epp of [[Manitoba (Canada)|Manitoba]], a member of the Progressive-Conservative party, served as national Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, more recently as Minister for Health. Canadian Mennonite politicians have belonged to many different political parties and have expressed widely varying political views, including positions on military defense which are in tension with Mennonite pacifist teachings. In recent years North American Mennonite scholars and church leaders have addressed [[Church-State Relations|church-state]] issues in numerous conferences and publications. The issues of war [[Taxes|taxes]] and of registration for the military draft surfaced during and after the [[Vietnam War (1954-75)|Vietnam War]]. Two Mennonite theologians who gained wider prominence for their writings were [[Kaufman, Gordon D. (1925-2011)|Gordon Kaufman]] of Harvard Divinity School and </span>[[Yoder, John Howard (1927-1997)|John Howard Yoder]]<span class="Apple-style-span"> of Associated Mennonite Biblical Seminaries and Notre Dame University. Anabaptist-Mennonite thinking has been particularly influential in the liberation theology of some Latin American theologians.</span> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | Mennonite churches which are the product of mission work in Asia, [[Africa|Africa]], and Latin America have expressed varying political attitudes in their different circumstances. Anabaptist-Mennonite teachings have often combined with minority religious status to place Mennonites in a situation of dissent. Japanese Mennonites have joined other Christians in that country in resisting the remilitarization of Japan and the revival of [[Shintoism|Shintoism]] as a state religion. Taiwanese Mennonite political attitudes have been shaped by their status as ethnic Taiwanese who have been politically dominated by Mandarin- speaking Nationalists from the Chinese mainland. The political attitudes of African Mennonites have been shaped by inter-tribal relationships. The Brethren in Christ in [[Zimbabwe|Zimbabwe]], for example, were mainly from the Ndebele tribe which took second place to the majority Shona tribe in the violent struggle for national independence. In [[Ethiopia|Ethiopia]] in 1982 a Marxist government suppressed the Mennonite Church ([[Meserete Kristos Church|Meserete Kristos Church]]), expropriated church properties, and detained Mennonite church leaders without charges and without trial for more than four years. In Latin America, Spanish-speaking Mennonite churches are generally small in size and part of a Protestant minority in the context of a historic Catholic church-state alliance. | ||

| + | As Mennonites across the world are scattered into nearly 150 organized bodies on the five continents and Australia, generalizations about political attitudes are difficult to make. In recent years the [[Mennonite World Conference]] has become an increasingly significant forum for inter-Mennonite sharing of religious and political concerns. | ||

= Bibliography = | = Bibliography = | ||

Epp, Frank H. "An Analysis of National Socialism in the Mennonite Press in the 1930's." PhD diss. U. of Minnesota, 1965. | Epp, Frank H. "An Analysis of National Socialism in the Mennonite Press in the 1930's." PhD diss. U. of Minnesota, 1965. | ||

| Line 40: | Line 35: | ||

Yoder, John Howard. <em>The Politics of Jesus.</em> Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1972. | Yoder, John Howard. <em>The Politics of Jesus.</em> Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1972. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{GAMEO_footer|hp=Vol. 5, pp. 710-711|date=1990|a1_last=Juhnke|a1_first=James C|a2_last=|a2_first=}} | {{GAMEO_footer|hp=Vol. 5, pp. 710-711|date=1990|a1_last=Juhnke|a1_first=James C|a2_last=|a2_first=}} | ||

Latest revision as of 16:30, 24 February 2017

Mennonite attitudes toward political parties and authorities have differed widely among the many groups in the Mennonite mosaic and within the more than 50 countries to which Mennonites have scattered. Mennonite attitudes have reflected both the Anabaptist teaching that governments are ordained by God to maintain order and the teaching that government authority is limited and not to be obeyed when it contradicts the will of God (civil disobedience). Modern warfare and the Mennonite refusal of military service have provided the focus for the shaping of Mennonite attitudes in the modern era of nationalism and militarism.

Mennonites generally have not shown a preference for either liberal or authoritarian systems, but have honored any government which offered them toleration and autonomy. Thus Mennonites gave their deference and appreciation to the tsars of Russia, to the dictator Alfredo Stroessner of Paraguay, but also to the liberal democracies of the United States and Canada and to the "secular state" program of the Congress Party in India. The severe suffering of Mennonites under Russian Communism produced a strong anti-Communist sentiment, especially among emigrés from Russia. In the 1930s some Mennonites in Canada and Paraguay expressed sympathies for the anti-Communist stance of National Socialism in Germany.

Modern democratic theory and practice have changed the context of Mennonite political attitudes and behavior. In the 17th and 19th centuries in Europe, Mennonites had the status of subjects with personal obligations to rulers or princes. In this relationship Mennonites often traded special taxes for toleration. In modern democratic states which claim to derive authority from the people, Mennonites have had the status of citizens who are responsible for the civic order. The earliest Mennonite experience with democratic pluralism was in America. Historian Richard MacMaster has shown (MEA 1), contrary to earlier opinions, that Mennonites in colonial Pennsylvania voted in elections and gave support to the ruling pacifist Quaker party which protected their interests. The American War for independence (1775-83), in which the willingness to bear arms and swear a loyalty oath became tests of citizenship, removed Mennonites from political participation and made them "more than ever a people apart." American Mennonite immigrants of Swiss background maintained a stricter two-kingdom dualism and separation from politics than did the Dutch-Russian immigrants of the 1870s and 1880s in America. Some American Mennonites became active in state and national politics, but they needed to drift away from their Mennonite connections. Old Order Mennonites, Old Order Amish, and other traditionalist groups have attempted a strict separation from political participation.

Mennonites who have an official or unofficial stance of political non-involvement often do have political preferences. Some theologically conservative Mennonites influenced by dispensationalist teachings have been keenly interested in contemporary events, often relating to the State of Israel, which are said to reveal God's plan for the fulfillment of history. A study of the political socialization of "Old" Mennonite (MC) secondary school students (Leatherman, 1960) showed that Mennonites, compared to an American norm, were distinctively non-involved in partisan political activity but that they also reported unusually high identification with the Republican Party (70 percent). According to this study, historical factors which fostered the Republican preference included Mennonite opposition to slavery and to the Democrat South's Civil War rebellion against the national government (American Civil War), a positive response to generous Republican land policies on the frontier, and the concentration of Mennonite settlements in strongly Republican states.

In a sociological study of five Mennonite and Brethren in Christ groups in the United States and Canada in 1972 (Kaufman/Harder, 1975), 76 percent of the respondents said that church members should vote in public elections. Of those who expressed a party preference, three-fourths of the American Mennonites identified with the Republican Party. In Canada the party preferences were more evenly divided: 40 percent Conservative, 32 percent Liberal, 20 percent Social Credit. A historical study of the political acculturation of Kansas Mennonites (Juhnke, 1975) showed that the distinctiveness of Mennonite party preferences changed over time. Until 1940 Kansas Mennonites (mostly General Conference and of Dutch-Russian background) scattered their votes among the political parties in about the same percentages as their non-Mennonite neighbors. There was substantial variation among congregations, however. The Swiss-Volyhnians were less strongly Republican than were the Dutch-Russian Alexanderwohlers. In the 1940 election, when it was clear that President Franklin D. Roosevelt was leading the country into war, the Kansas Mennonites voted in Republican majorities which were distinctively larger than their non-Mennonite neighbors. The Democrat party was identified with war, as it had been in the Civil War and again in World War I. Issues of war and peace affected American Mennonite political attitudes and behavior more than did issues of social welfare, although Mennonites voted in especially large numbers in which "moral issues" such as Prohibition or capital punishment were at stake.

Since World War II Mennonites in the five western provinces of Canada became more extensively involved as voters and as officeholders in provincial and national politics than Mennonites have ever been anywhere. In recent elections from 3-10 Mennonites have stood for provincial offices while 15 or more have been nominated for national offices. In 1979-80 Jake Epp of Manitoba, a member of the Progressive-Conservative party, served as national Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, more recently as Minister for Health. Canadian Mennonite politicians have belonged to many different political parties and have expressed widely varying political views, including positions on military defense which are in tension with Mennonite pacifist teachings. In recent years North American Mennonite scholars and church leaders have addressed church-state issues in numerous conferences and publications. The issues of war taxes and of registration for the military draft surfaced during and after the Vietnam War. Two Mennonite theologians who gained wider prominence for their writings were Gordon Kaufman of Harvard Divinity School and John Howard Yoder of Associated Mennonite Biblical Seminaries and Notre Dame University. Anabaptist-Mennonite thinking has been particularly influential in the liberation theology of some Latin American theologians.

Mennonite churches which are the product of mission work in Asia, Africa, and Latin America have expressed varying political attitudes in their different circumstances. Anabaptist-Mennonite teachings have often combined with minority religious status to place Mennonites in a situation of dissent. Japanese Mennonites have joined other Christians in that country in resisting the remilitarization of Japan and the revival of Shintoism as a state religion. Taiwanese Mennonite political attitudes have been shaped by their status as ethnic Taiwanese who have been politically dominated by Mandarin- speaking Nationalists from the Chinese mainland. The political attitudes of African Mennonites have been shaped by inter-tribal relationships. The Brethren in Christ in Zimbabwe, for example, were mainly from the Ndebele tribe which took second place to the majority Shona tribe in the violent struggle for national independence. In Ethiopia in 1982 a Marxist government suppressed the Mennonite Church (Meserete Kristos Church), expropriated church properties, and detained Mennonite church leaders without charges and without trial for more than four years. In Latin America, Spanish-speaking Mennonite churches are generally small in size and part of a Protestant minority in the context of a historic Catholic church-state alliance.

As Mennonites across the world are scattered into nearly 150 organized bodies on the five continents and Australia, generalizations about political attitudes are difficult to make. In recent years the Mennonite World Conference has become an increasingly significant forum for inter-Mennonite sharing of religious and political concerns.

Bibliography

Epp, Frank H. "An Analysis of National Socialism in the Mennonite Press in the 1930's." PhD diss. U. of Minnesota, 1965.

Epp, Frank H. Mennonites in Canada, 1920-1940: a People's Struggle for Survival. Toronto: Macmillan, 1982: 543ff.

Juhnke, James C. A People of Two Kingdoms. Newton, KS: Faith and Life, 1974.

Kauffman, J. Howard and Leland Harder, eds. Anabaptists Four Centuries Later: a Profile of Five Mennonite and Brethren in Christ Denominations. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1975: 150-69.

Kaufman, Gordon D. Theology for a Nuclear Age. Manchester, England: Manchester U. Press, 1985.

Leatherman, Daniel B. "The Political Socialization of Students in the Mennonite Secondary Schools." MA thesis, U. of Chicago, 1960.

MacMaster, Richard K. Land, Piety, Peoplehood: the Establishment of Mennonite Communities in America, 1683-1790. The Mennonite Experience in America, vol. 1. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1985.

Redekop, John H. "Mennonites and Politics in Canada and the United States." Paper for Conference on Mennonite Studies in North America, 1982.

Wittlinger, Carlton O. Quest for Piety and Obedience: the Story of the Brethren in Christ. Nappanee, IN: Evangel Press, 1978: 405ff.

Yoder, John Howard. The Politics of Jesus. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1972.

| Author(s) | James C Juhnke |

|---|---|

| Date Published | 1990 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Juhnke, James C. "Political Attitudes." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1990. Web. 18 Apr 2024. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Political_Attitudes&oldid=147306.

APA style

Juhnke, James C. (1990). Political Attitudes. Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 18 April 2024, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Political_Attitudes&oldid=147306.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 5, pp. 710-711. All rights reserved.

©1996-2024 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.