Difference between revisions of "Russia"

| [checked revision] | [checked revision] |

m (Text replace - "<em>Mennonitisches Lexikon</em>, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. III," to "''Mennonitisches Lexikon'', 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. III,") |

|||

| (5 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 666: | Line 666: | ||

|} | |} | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | '''Sources''': | + | '''Sources''':<br /> |

| − | Friesen, Peter M. <em>Die Alt-Evangelische Mennonitische Brüderschaft in Russland (1789-1910) im Rahmen der mennonitischen Gesamtgeschichte</em>. Halbstadt: Verlagsgesellschaft "Raduga", 1911. | + | Dirks, Heinrich. <em>Statistik der Mennonitengemeinden in Russland Ende 1905 (Anhang zum Mennonitischen Jahrbuche 1904/05)</em>. Gnadenfeld: Dirks, 1906.<br /> |

| − | + | Friesen, Peter M. <em>Die Alt-Evangelische Mennonitische Brüderschaft in Russland (1789-1910) im Rahmen der mennonitischen Gesamtgeschichte</em>. Halbstadt: Verlagsgesellschaft "Raduga", 1911.<br /> | |

| − | <em>Die Mennoniten-Gemeinden in Russland während der Kriegs- und Revolutionsjahre 1914 bis 1920.</em> Heilbronn: Kommissions-Verlag der Mennonitische Flüchtlingsfürsorge, 1921. | + | <em>Die Mennoniten-Gemeinden in Russland während der Kriegs- und Revolutionsjahre 1914 bis 1920.</em> Heilbronn: Kommissions-Verlag der Mennonitische Flüchtlingsfürsorge, 1921.<br /> |

Quiring, Jacob. <em>Die Mundart von Chortitza in Süd-Russland.</em> München: Druckerei Studentenhaus München, Universität, 1928. | Quiring, Jacob. <em>Die Mundart von Chortitza in Süd-Russland.</em> München: Druckerei Studentenhaus München, Universität, 1928. | ||

| Line 750: | Line 750: | ||

== 2011 Update == | == 2011 Update == | ||

| − | The following table summarizes the number of Mennonites in Russia between 2000 and | + | The following table summarizes the number of Mennonites in Russia between 2000 and 2012: |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | </ | + | <div align="center"> |

| + | {| border="1" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | !Membership<br>in 2000 | ||

| + | !Membership<br>in 2003 | ||

| + | !Membership<br>in 2006 | ||

| + | !Membership<br>in 2009 | ||

| + | !Membership<br>in 2012 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |<div align="right">3,350</div> | ||

| + | |<div align="right">5,000</div> | ||

| + | |<div align="right">3,000</div> | ||

| + | |<div align="right">3,000</div> | ||

| + | |<div align="right">3,000</div> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| − | |||

= Bibliography = | = Bibliography = | ||

<h4>Introduction</h4> This is a selected bibliography. For a complete list of books and periodicals (1950s), see the bibliographies of the dissertations by Adolf Ehrt and David G. Rempel. For additional information see also the various articles dealing with settlement and institutions of Russia. | <h4>Introduction</h4> This is a selected bibliography. For a complete list of books and periodicals (1950s), see the bibliographies of the dissertations by Adolf Ehrt and David G. Rempel. For additional information see also the various articles dealing with settlement and institutions of Russia. | ||

| Line 826: | Line 824: | ||

<em>Mennonite Life</em> (North Newton, 1946- ). | <em>Mennonite Life</em> (North Newton, 1946- ). | ||

| − | + | ''Mennonitische Rundschau'' (1877- ,Winnipeg, 1924- ). | |

<em>Mennonitisches Jahrbuch</em>, ed. Heinrich Dirks (Gross-Tokmak, 1901-14). | <em>Mennonitisches Jahrbuch</em>, ed. Heinrich Dirks (Gross-Tokmak, 1901-14). | ||

| Line 862: | Line 860: | ||

Gutsche, Waldemar. <em>Westliche Quellen des russischen Stundismus.</em> Kassel, 1956. | Gutsche, Waldemar. <em>Westliche Quellen des russischen Stundismus.</em> Kassel, 1956. | ||

| − | Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. | + | Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. ''Mennonitisches Lexikon'', 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. III, 573-581. |

Hiebert, P. C. and Orie O. Miller. <em>Feeding the Hungry, Russia Famine 1919-1925. </em>Scottdale, 1929. | Hiebert, P. C. and Orie O. Miller. <em>Feeding the Hungry, Russia Famine 1919-1925. </em>Scottdale, 1929. | ||

Revision as of 00:58, 16 January 2017

Introduction

Russia is the largest country in the world, with an area of 17,075,400 km2 (6,592,800 square miles). It occupies most of northern Eurasia and had an estimated population in 2008 of 142,008,838. Once an empire ruled by Romanov tsars, Russia became the largest republic in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) after the Russian Revolution of 1917. After the fall of Soviet Union in 1991, the Russian Federation was founded, with 83 federal subjects.

Russia is populated primarily by Slavic peoples, although a large number of minority groups are found in the country -- some of them belonging to the Mongolian race which invaded Russia from time to time in its early history. Other nationalities immigrated into Russia, during its early history coming from Scandinavia, and later, when rulers were interested in occupying the vast uninhabited areas along the Volga River and in the Ukraine, from Western Europe.

In 2002, 79.8% of the population was ethnic Russian, with 3.8% Tatars, 2.0% Ukrainian, 1.1% Chuvash, 0.9% Chechen, and 0.8% Armenians. The Russian Orthodox Church is the largest religious group in the country with approximately 100 million citizens considering themselves Russian Orthodox Christians in 2007. Islam, Buddhism, and Judaism are Russia’s other traditional religions.

1959 Article

Russian Immigration Policy

Already under the rule of Elizabeth "Nine Articles" were drawn up on 26 September 1752, to promote immigration into Russia. On 4 December 1762, Catherine II issued a manifesto inviting foreign settlers from Western European countries to settle in the vast uninhabited areas of Russia, which was followed by the better known second Manifesto of 22 July 1763 patterned after the Potsdam Edict of 1685. Prospective settlers were extended the following rights and privileges: (1) free board and transportation from the Russian boundary to the place of settlement; (2) the right to settle in any part of the country and to pursue any occupation; (3) a loan for the building of houses, etc.; (4) perpetual exemption from military and civil service; (5) exemption from payment of taxes for a period of years; (6) free exercise of religious practices, and to those who founded agricultural settlements, the right to build and control their own schools and churches; (7) the right to do mission work among non-Christians; (8) the right of local self-government for agricultural communities; (9) the right of every family to import its possessions free of duty; (10) to those who established factories with their own capital, the right to buy serfs and peasants.

In order to inaugurate and supervise a large-scale immigration and colonization program, the Bureau of Guardianship of the Foreign Colonists was established. It supervised the work of recruiting colonists (by agents), making land available to them, the actual settling, etc. This Bureau had the status of a separate ministry which was responsible to the empress. Gregory Orlov was its first chairman.

The Manifesto of 1763 was publicized in foreign countries through embassies and agents. In some countries which did not favor emigration the publicity failed. The only countries in which the Russian representatives met no obstacles in making known the colonization policy of their government were the small states of South and West Germany. In some of these there was widespread discontent and a desire for emigration, but even here the number of those who responded to the call was small. In 1764, when the government employed professional agents, the picture changed. Copies of the Manifesto and numerous broadsides were distributed, which created an emigration fever in some of the German states. German settlements were established in the province of St. Petersburg in 1765-1766. However, the largest originated along the lower Volga River, where over 100 villages were founded in 1764-1767. None of these were Mennonite.

Ukraine

The major goal of foreign settlers during the remainder of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century was New Russia, later known as Ukraine. This territory, located in South Russia and inhabited only by nomadic peoples and Cossacks, finally came under complete possession of Russia with the annexation of the Crimea in 1783. Beginning in 1774 this territory was administered by the Viceroy Potemkin, who was interested in colonizing this largely uninhabited area. Much of the land was granted to court officials, army officers, and government officials. A large number of peasants from central Russia were settled on the Dnieper River. Potemkin's agents tried to induce citizens of Danzig, Albania, Greece, Sweden, and other countries to settle in the Ukraine. Some Greek, Armenian, and Swedish settlers established settlements in 1778-81. In Danzig Potemkin's agent Georg von Trappe began his campaign on 19 June 1786. Some non-Mennonite families established the Old Danzig settlement in the province of Kherson.

About this time the Russian Count Rumyantsev-Zadunaisky, who had frequently been through the Mennonite settlements in the vicinity of Danzig, called the attention of the Russian government to them as prospective settlers. Georg von Trappe also called Potemkin's attention to the Mennonites whom he had met. In August 1786 an invitation was extended to the Mennonites, and von Trappe became the chief agent for their immigration into Russia.

At first the Mennonites received this invitation with great reserve in order not to antagonize the Danzig city council, which was opposed to the emigration. Jakob Höppner and Johann Bartsch were sent to Russia to inspect the land and make necessary arrangements for the immigration. After inspecting the proffered land and interviewing Potemkin and Catherine II (13 May, 1787) and other authorities, they returned to report their findings to their constituency. Meanwhile von Trappe had been active in promoting the emigration in Danzig. In a printed broadside dated 29 December 1787 (Mennonite Life April 1951, 37), he praised the conditions of the settlement highly and invited those interested to meet on 19 January 1788 at the Russian Embassy in Danzig. During that year 228 families left for Russia, followed by additional groups, a total of 462 families (B. H. Unruh, 231) who established the first Mennonite settlement, Chortitza, in the province of Ekaterinoslav in the Ukraine. The Chortitza settlement is also known as the Old Colony since it was the first settlement. Between 1798 and 1802 the stream of immigrants subsided, until new difficulties in the home country caused a new wave of immigration to Russia.

On 20 February 1804, Alexander I issued another Manifesto. During 1803-1806 some 365 Mennonite families went to Russia, some of which stopped at the Chortitza settlement. Beginning in 1804, they settled in the province of Taurida on the Molotschnaya, a river from which the name of the Molotschna settlement was derived, some 100 miles southeast of the Chortitza settlement. From time to time additional groups followed until gradually 60 villages were established. In 1835 the migration to the Molotschna came to a close with an estimated total of 1,200 families or 6,000 persons.

Chortitza and Molotschna constituted the two original Mennonite settlements of the Ukraine; from them most of the daughter settlements in Russia originated.

Although by this time the Russian government was no longer interested in settling foreigners in Russia, two more settlements, with some 500 families, were established in the province of Samara, viz., the Am Trakt settlement (begun in 1855) and the Alexandertal settlement (begun in 1859). The total immigration of Mennonites from Danzig and Prussia to Russia during the years 1788-1870 was about 2,300 families, of whom approximately 462 families went to Chortitza, 1,200 to the Molotschna, and 500 to Samara; 80 families supposedly remained in Vilna on their way to the Ukraine. B. H. Unruh (230) estimated that the total number of immigrants was 10,000. These families came from the following communities and churches: Danzig, Marienburg, Elbing, Tiegenhof, Heubuden, Orloff, Ladekopp, Fürstenwerder, Rosenort, and Tiegenhagen. By no means all the immigrants were experienced farmers. Particularly the first group settling in Chortitza was largely composed of poorer laborers, primarily because it was harder for the well-to-do class to obtain permission to leave the country. The Molotschna and Samara settlements, having numerous prosperous and experienced farmers and better land, made more rapid progress economically and culturally than did Chortitza.

Reasons for Migration

The Mennonites of Danzig and Prussia had always been a minority in their homeland, tolerated at times because of the economic advantages which the rulers derived from them and at other times oppressed because of their peculiar religious views, their unwillingness to serve in the army, and their rapid spread in the rural areas. In the early days they had been welcomed as good farmers who drained and cultivated the uninhabited swamps of the Vistula River. As Mennonites, however, they were not considered full-fledged citizens. At any time when their service was not needed they were oppressed. The occupations open to them were restricted from time to time (see Danzig Edict of 10 November 1749, Mennonite Life, April 1951, 36). In 1789 a new "Mennonite Edict" prohibited the Mennonites from purchasing new land, basically because the Mennonites with their large families were buying large quantities of land and thus weakening the rural manpower available for military service. In 1748 the Mennonites in 21 villages of the Werder possessed 392 Hufen (a Hufe is about 40 acres) of the 2,418 of this territory; by 1788 they owned 683 Hufen, thus in 40 years nearly doubling their holdings. In 1772 they purchased a total of 400 farms in Prussia. In 1783-1787 the number of families increased from 2,240 to 2,894, which was an increase of 654 families or 3,083 persons in four years (H. Quiring, Mennonite Life, April 1951, 37).

Thus the reasons for the great interest of the Mennonites of the Vistula River in emigration become apparent. Their rapid increase in numbers, combined with the restrictions in the purchase of land and the occupations open to them, in addition to the uncertainties regarding the preservation of their religious heritage, e.g., the practice of nonresistance, induced them to consider invitations to other countries.

The Mennonites, however, as noted above, were not the first to receive the invitation to settle in Russia. Catherine II and her agents had tried to attract citizens of many other countries before their attention was called to the Mennonites. And the Mennonites never constituted more than a minority in the total number of immigrants coming to Russia from Germany and other countries. The total population of people of German descent in Russia during World War I was estimated somewhere around 2,000,000, of whom only some 100 to 120 thousand (5 per cent) were Mennonites. Special "privileges" accorded Mennonites when they went to Russia have probably been overstated. There was, to be sure, some variation in the conditions under which settlements in general were established, but they were probably not due to the fact of differing religious faith (Mennonite or non-Mennonite). Even exemption from military service, which had already been offered as an inducement in the Manifesto of 1763, was granted also to non-Mennonite settlers. The ultimate differences in treatment between the Mennonites and others were possibly due rather to the fact that the Mennonites, because of their deeply rooted religious convictions, more persistently claimed exemption from military service when this "privilege" was threatened. However, 1874-1880 when one third of all Mennonites from Russia moved to the United States and Canada, many thousands of non-Mennonite Russo-Germans including Catholics, Lutherans, Reformed, and Pietists also moved to North and South America partly because of the loss of their "privileges."

Privileges and Administration

The rights, privileges, and administration of the foreign settlers were not stable and uniform throughout all times nor for all settlements. In general the settlers were under the laws and jurisdiction specifically made for "foreign colonists," who were originally responsible to the Bureau of Guardianship of Foreign Colonists, which had its quarters in St. Petersburg. In 1818 a Fürsorge Komitee (Guardian's Committee) was established by the Russian government, with its seat first at Kherson, later at Ekaterinoslav, and finally at Odessa, which was originally subject to the Minister of Interior. In 1871 the Fürsorge-Komitee was abolished and the foreign settlers including the Mennonites became subject to the local authorities of their respective districts. The German system of self-administration under a Schulze in the village and an Oberschulze of the settlement was practiced by the Mennonites from the beginning until the Revolution of 1917 removed all semblance of privilege and independence from the Mennonites of Russia.

The basic condition under which all colonists were admitted to Russia was Catherine's Manifesto of 22 July 1763 (for a complete text, see D. H. Epp, Chortitzer Mennoniten, 1889, 3). In general this remained the policy for all settlements, although the conditions were not always so generous. In recent times, particularly in America, the charge has been made that the Mennonites of Russia promised not to do any evangelistic or missionary work in Russia. The fact is, however, that none of the Mennonite "privileges" contained such a restriction. Hence this charge must have reference to the original Manifesto of 1763, which states (VI, 1) that the foreign colonists settling in Russia were to have the right to exercise their religion freely in accord with their church rules and practices without any molestation, but that "everyone is warned that none of the Christian believers residing in Russia should under any pretext be persuaded or misled to accept or join the faith and the church" of the foreign colonists. This restriction is followed by a statement that "all the nationalities of the Mohammedan faith living within Russia can be persuaded to accept the Christian religion without any restriction." This makes it clear that the restriction was meant to protect the Russian Orthodox Church against proselyting, but that the foreign settlers had ample opportunity to do mission work among non-Christian citizens of Russia. This Manifesto was dated 1763, and the first agreement made between the Mennonite settlers and the Russian government was dated 3 March 1788, which was 25 years later. Neither this first agreement of 1788 nor any of the following contains a clause restricting mission work in Russia. It is likely that very few Mennonites who settled in Russia ever heard of the restricting clause of the Manifesto of 1763.

The twenty articles (German text in D. H. Epp, 25 ff.) which Höppner and Bartsch presented to Potemkin and which were later confirmed by the government in St. Petersburg including Catherine II contain the terms under which the Mennonites would come to Russia; the first deals with religious freedom, the second with the settlement conditions, the third and fourth with tax exemptions, the fifth and sixth with the development of industry and a loan by the government, the seventh and eighth with the guarantee of freedom of religion and exemption from military service for "eternal ages." The remaining articles, the ninth to the twentieth, deal with the details of travel to Russia and the settlement there. On the margins the government representatives approved or qualified the requests. Articles seven and eight, pertaining to the guarantee of religious freedom and exemption from military service "for all times," are thus annotated, "This shall be done in accordance with their practice" and "they shall be exempted from military service." In 1800 the Mennonites of Russia received a Privilegium under Tsar Paul I confirming the rights they had received before (printed by D. H. Epp, 97). Special rights were given to the Mennonites who settled later in the province of Samara.

Early Developments (1789-1850)

The Chortitza settlement, being the first, established in an entirely new environment, under the most primitive conditions differing greatly from those of the Vistula Delta, and by settlers who were poor and inexperienced in agriculture, underwent the greatest hardships, affecting the economic, cultural, and religious life. The leaders Bartsch and Höppner were not trusted, and there were no ordained religious leaders. Only under the greatest privations were the early difficulties of pioneering overcome. The promises of the government were either not fulfilled at all or not according to schedule. Theft by officials was common. The Molotschna settlers, many of whom had stopped at the Chortitza settlement, gained much information and experience and settled under more favorable conditions. Many of them were more prosperous to begin with and of a better cultural and spiritual background. This second settlement soon made greater cultural, economic, and religious advances.

A great promoter was Johann Cornies (1789-1848). Through his personal work and as the chairman of the Agricultural Association he did much to improve the economic and educational life of both settlements, particularly of the Molotschna. Gradually the Mennonites shifted the emphasis from the raising of cattle, sheep, and horses to that of grains, particularly winter wheat. Primitive agricultural machinery was replaced by advanced implements produced in Mennonite factories. Chortitza, Alexandrovsk, Halbstadt, and Orloff were leading towns in industrial enterprises and in cultural development. By the time of the death of Johann Cornies the foundation for this development had been laid. But in the matter of providing settlement opportunities for the landless population of both settlements only a beginning had been made by a spearheading group. The conservative landowning class of farmers did not yet realize their responsibility toward the less fortunate majority of the population of both settlements. Only gradually was the traditional system of mutual aid broadened, which enabled the Mennonites of Russia to establish many daughter settlements not only in the Ukraine, but also in other provinces of European Russia and Siberia, through co-operative purchase of land and loans to new settlers.

In educational and religious practices the pioneers in Russia were extremely conservative, preserving the practices of the old homeland. Ministers read their sermons monotonously. Very little progress was made in challenging the congregations and individuals in their ethical and religious practices and in awakening their social, missionary, and evangelistic responsibilities. The schools were primitive and restricted to the teaching and reading of the Bible and Bible stories, the catechism, the primer, and elementary arithmetic. Teachers were poorly prepared and the school buildings and equipment inadequate.

Daughter Settlements

The number of landless Mennonites increased from generation to generation, particularly since the government did not permit the subdivision of a farm, which consisted as a rule of 176 acres (65 desiatinas). The large surplus land tracts in connection with the settlements were generally rented by the well-to-do farmers. The landless usually obtained a small parcel of land at one end of the village and worked as farm hands, industrial workers, etc. They were known as Anwohner. A typical situation was that in the Molotschna settlement in 1865, when there were 1,384 landed farmers and 2,356 landless workers in the villages. Only the landowners, comprising less than one third of the population, had civic and economic rights; the other two thirds had none. A committee known as the Landlosen-Kommission was formed in 1863 to represent the cause of the landless and appeal to the Fürsorge Komitee for remedial action. Finally the surplus land of the Molotschna settlement was distributed among the landless. In addition to this, a fund was established for the purchase of land for oncoming generations. By painful experience the Mennonites of the Molotschna and Chortitza learned to help and to provide for the new generations of landless by establishing daughter colonies.

J. Ewert's study of the increase of the population and the land owned by Mennonites from 1789 to 1910 revealed that approximately 8,500 (the estimate is now 10,000) immigrants established the Chortitza, Molotschna, Alexandertal, and Am Trakt settlements, which had a population of 34,500 by 1859, while the occupied land area remained the same, viz., 501,400 acres. After the great immigration of the Mennonites to America in 1874-1880, the population again rapidly increased. In 1910 Ewert estimated the population of Mennonites in Russia as 100,000, owning a total acreage of 1,798,948, or an average of 18 acres per person (Der Praktische Landwirt, December 1926, No. 12, pp. 12 ff.) (Some estimates are higher; see Agriculture among the Mennonites of Russia). Adolf Ehrt estimated that in 1860 the Mennonites averaged 14 acres per person, and in 1914 16 acres. However, this land increase took place primarily in the daughter settlements. The acreage of the mother settlements remained more or less unchanged (Ehrt, 84). In 1860 the mother colonies owned seven times as much land as the daughter colonies, and in 1914 they owned equal amounts (Ehrt, 83).

The increase in property owned by the Mennonites of Russia can be estimated from the taxation for the maintenance of the forestry service or alternative service program. The records reveal that in 1908 the reported property value was 194,000,000 rubles, while by 1914 this had increased to 276,000,000 rubles (Ehrt, 70). No doubt this is an underestimate, since probably not all persons had been reached by the census. Land holdings by Mennonites increased proportionally beyond the growth of the population. The large increase of land ownership was partly due to the purchase of scattered large estates outside the main settlements. Before World War I there were 384 Mennonite large estate owners, who owned 810,000 acres, making an average of 283 acres; the average evaluation of such an estate in 1914 was 200,000 rubles. The large estate owners, though numbering only 1.9 per cent of the Mennonite population, contributed one third of the total, or 80,000 rubles, annually for the maintenance of the forestry service on the basis of an assessment on owned land. The largest Mennonite estate consisted of 50,000 acres (Ehrt, 87).

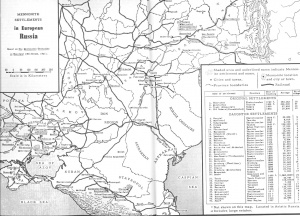

During the second half of the 19th century the establishment of daughter settlements was restricted primarily to European Russia, first in the territories immediately surrounding the two settlements, then in the Crimea, then in the foothills of the Caucasian Mountains, and later (after 1890 except for Turkestan 1882, 1884) in the eastern provinces of Central European Russia, such as Orenburg, and in Asiatic Russia. Following is a list of the settlements with name, province, the year of founding, number of villages, acreage, and population. Separate articles on each of the settlements will be found in GAMEO. The Russian names, usually Germanized, appear here in an Anglicized form, while the German ones have been retained. (See also article Villages)

Tables and Statistics

Mother Settlements

| Name | Province | Founded | Villages | Acreage | Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chortitza | Ekatinoslav | 1789 ff

|

19

|

1789: 89,100; 1917: 405,000

|

1819: 2,888; 1941: 13,965

|

| Molotschna | Taurida | 1804 ff

|

60

|

1835: 324,000

|

1835: 6,000; 1926: 17,347

|

| Am Trakt | Samara | 1853 ff

|

10

|

1897: 44,134

|

1897: 1,176

|

| Alexandertal | Samara | 1859 ff

|

8

|

1870: 26,500; 1917: 53,500

|

1913: 1,144

|

Daughter Settlements

| Name | Province | Mother Settlement | Founded | Villages | Acreage | Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bergthal | Ekaterinoslav | Chortitza | 1836-1852 | 5

|

30,000

|

1874: 3,000

|

| Jewish Settlement (Judenplan) | Kherson | Chortitza | 1847 | 6

|

5-6 families per village

| |

| Chernoglaz | Ekaterinoslav | Chortitza | 1860 | 1

|

2,700

|

130

|

| Crimea | Taurida | Molotschna | 1862ff. | ca. 25 & estates

|

1929: 108,000

|

1926: 4,817

|

| Kuban | Kuban | Chortitza/Molotschna | 1862 | 2

|

17,550

|

1904: 2,000

|

| Fürstenland | Taurida | Chortitza | 1864-1870 | 7

|

19,000

|

1874: 1,100

|

| Borozenko | Ekaterinoslav | Chortitza | 1865-1866 | 6

|

18,000

|

1910: 600

|

| Friedensfeld (Miropol) | Ekaterinoslav | Molotschna | 1868 | 1

|

5,400

|

|

| Brazol (Schönfeld) | Ekaterinoslav | Molotschna | 1868 | 4 (plus estates)

|

1868: 14,000; 1910: 187,000

|

1917: 2,000

|

| Neu-Schönwiese (Dmitrovka) | Ekaterinoslav | Schönwiese-Chortitza | 1868 | 1

|

3,788

|

|

| Tempelhof | Stavropol | Molotschna | 1868 | 2

|

||

| Yazykovo (Nikolaifeld) | Ekaterinoslav | Chortitza | 1869 | 6

|

23,315

|

1930: 2,200

|

| Nepluyevka | Ekaterinoslav | Chortitza | 1870 | 2

|

10,800

|

1910: 550

|

| Andreasfeld | Ekaterinoslav | Chortitza | 1870 | 3

|

10,620

|

|

| Baratov | Ekaterinoslav | Chortitza | 1872 | 2 (4)

|

1872: 9,800

|

1905: 2,569

|

| Zagradovka | Kherson | Molotschna | 1871 | 16

|

57,445

|

1922: 5,429

|

| Schlachtin | Ekaterinoslav | Chortitza | 1874 | 2

|

10,800

|

1910: 1,000

|

| Neu-Rosengart | Ekaterinoslav | Chortitza | 1878 | 2

|

1,800

|

1910: 250

|

| Wiesenfeld | Ekaterinoslav | Chortitza | 1880 | 1

|

23,306

|

|

| Aulie-Ata | Turkestan | Molotschna | 1882 | 6

|

21,600

|

1910: 1,000

|

| Ak-Mechet | Khiva | Am Trakt | 1884 | 1

|

13

|

25 families

|

| Memrik | Ekaterinoslav | Molotschna | 1885 | 10

|

32,400

|

1,367

|

| Alexandropol | Ekaterinoslav | Molotschna | 1888 | 1

|

?

|

15 families

|

| Samoylovka | Kharkov | Molotschna | 1888 | 2

|

?

|

1905: 239

|

| Milorodovka | Ekaterinoslav | Chortitza | 1889 | 2

|

5,670

|

1910: 200

|

| Ignatyevo | Ekaterinoslav | Chortitza | 1889-1890 | 7

|

38,132

|

1910: 1,400

|

| Naumenko | Kharkov | Chortitza/Molotschna | 1890 | 4 (3)

|

14,350

|

1905: 700

|

| Neu-Samara | Samara | Molotschna | 1890 | 14

|

1922: 91,000

|

1922: 3,670

|

| Borissovo | Ekaterinoslav | Chortitza | 1892 | 2

|

13,770

|

1910: 440

|

| Davlekanovo | Ufa | Molotschna/Samara | 1894 | 19 & Estates

|

1926: 30,000

|

1926: 1,831

|

| Orenburg (Deyevka) | Orenburg | Chortitza | 1894 | 14

|

63,660

|

1910: 1,400

|

| Suvorovka | Stavropol (Caucasus) | Zagradovka | 1894 | 2

|

10,800

|

80 families

|

| Orenburg (Molotschna) | Orenburg | Molotschna | 1898 | 8

|

29,700

|

1910: 1,000

|

| Olgino | Stavropol (Caucasus) | Mixed | 1895 | 2 (4)

|

12,150

|

80 families

|

| Bezenchuk | Samara | Alexandertal | 1898 | 3?

|

5,400

|

75

|

| Omsk | Akmolinsk & Tobolsk | Mixed | 1899 | 29 & Estates

|

108,000

|

|

| Don (Millerovo) | Don Region | Molotschna | 1900-1903 | 3

|

10,800

|

|

| Terek | Terek (Caucasus) | Molotschna | 1901 | 15

|

66,960

|

1905: 1,655

|

| Rovnopol (Ebenfeld) | Samara | Molotschna | 1903 | 1

|

8,250

|

|

| Trubetskoye | Kherson | Molotschna | 1904 | 2

|

118,800?

|

400

|

| Pavlodar | Semipalatinsk | Mixed | 1906 | 14

|

37,800

|

|

| Sadovaya | Voronezh | Chortitza | 1909 | 1?

|

16,052

|

|

| Slavgorod (Barnaul) | Tomsk | Mixed | 1908 | 58

|

135,000

|

1925: 1,373

|

| Zentral | Voronezh | Chortitza | 1909 | 1

|

7,358

|

|

| Arkadak | Saratov | Chortitza | 1910 | 7

|

25,500

|

1925: 1,500

|

| Bugulma | Samara | Alexandertal | 1910 | 1

|

2,700

|

|

| Kistyendey | Saratov | ? | 1910? | 1

|

||

| Minusinsk | Yeniseysk | Ignatyevo | 1913 | 2 (4)

|

10,800?

|

1918: 32 families

|

| Amur | Eastern Siberia | Mixed | 1927 | 20

|

1927: 1,300

| |

| Kuzmitsky (Alexandrovka) | Ekaterinoslav | Chortitza | ? | 1

|

1910: 4,860

|

1910: 200

|

| Eugenfeld | Ekaterinoslav | Chortitza | ? | 1

|

||

| Alexeyfeld | Kherson | Molotschna | ? | 1

|

Settlements in Russian Poland, including Hutterian Brethren

| Name | Province | Mother Settlement | Founded | Villages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. Prussian Settlements | ||||

| Deutsch-Wymysle | Warsaw | Przechovka | 1762

|

1

|

| Deutsch-Kazun | Warsaw | Culm-Graudenz | 1776

|

1

|

| Wola-Orsczynska | Plock, Warsaw | |||

| Karolswalde | Ostrog, Volhynia | Culm-Graudenz | 1780-1785

|

6

|

| Michalin | Kiev | Graudenz | 1787

|

|

| II. Swiss Volhynian Settlements | ||||

| Vignanka-Futtor | Dubno, Volhynia | Galacia | 1801

|

2

|

| Michelsdorf-Urszulin | Lublin, Poland | France | ?

|

2

|

| Eduardsdorf-Zahoriz | Dubno, Volhynia | Michelsdorf | 1837

|

2

|

| Horodyszcze | Novograd-Volynsk, Volhynia | Michelsdorf | 1837

|

2

|

| Kotozufka-Neumanufka | Novograd-Volynsk, Volhynia | Eduardsdorf | 1861

|

2

|

| III. Hutterian Settlements | ||||

| Vishenka | Tchernigov | Transylvania | 1770

|

1

|

| Radichev | Tchernigov | Vishenka | 1802

|

1

|

| Hutterthal | Taurida | Radichev | 1843

|

1

|

| Johannesruh | Taurida | Hutterthal | 1853

|

1

|

| Hutterdorf | Taurida | Hutterthal | 1857

|

1

|

| Neu-Hutterthal | Taurida | 1857

|

1

|

Sources:

Dirks, Heinrich. Statistik der Mennonitengemeinden in Russland Ende 1905 (Anhang zum Mennonitischen Jahrbuche 1904/05). Gnadenfeld: Dirks, 1906.

Friesen, Peter M. Die Alt-Evangelische Mennonitische Brüderschaft in Russland (1789-1910) im Rahmen der mennonitischen Gesamtgeschichte. Halbstadt: Verlagsgesellschaft "Raduga", 1911.

Die Mennoniten-Gemeinden in Russland während der Kriegs- und Revolutionsjahre 1914 bis 1920. Heilbronn: Kommissions-Verlag der Mennonitische Flüchtlingsfürsorge, 1921.

Quiring, Jacob. Die Mundart von Chortitza in Süd-Russland. München: Druckerei Studentenhaus München, Universität, 1928.

Explanation Regarding Russian Poland and Hutterian Brethren

Mennonites living in the Vistula Delta area gradually moved up the river into Poland, and Swiss Mennonites from Alsace-Lorraine and South Germany settled in Poland. Some of these settlements shared the political fate of Poland and passed under Russian rule in the Partitions of Poland (1772-1795) when Russian Poland was established (1815) and when it became a Russian province (1836-1914).

The Prussian Mennonites established Deutsch-Wymysle, Deutsch-Kazun, and Wola-Orsczynska at Plock, all near Warsaw; Karolswalde near Ostrog in Volhynia (six villages); and Michalin in the province of Kiev.

The Swiss Mennonites established the settlements of Vignanka-Futtor at Dubno in Volhynia, Michelsdorf-Urszulin near Lublin in Poland, Eduardsdorf-Zahoriz at Dubno in Volhynia, Horodyszcze (three villages) at Novograd-Volynsk in Volhynia, and Kotozufka-Neumanufka at Novograd-Volynsk in Volhynia (two villages). All of the Swiss and most of the Prussian Mennonites of Volhynia and Russian Poland went to the United States in the 1870s when the universal conscription law was introduced in Russia. Contact between the Mennonites of Russian Poland and those of Russia proper was infrequent. Some from Russian Poland later settled in the Molotschna, through whom a contact was established (see also Waldheim and Poland).

The first settlers of the Anabaptist-Mennonite family to enter Russia were the Hutterites, who established themselves on the estate Vyshenka of Count Rumyantsev, on the Desna River in the Ukraine, in 1770. The basis of this settlement was originally a private arrangement between the landowner and the Hutterites. Later the Hutterites shared in the Mennonite privileges and were treated similarly. Soon the Bruderhof was moved to the crown land of Raditchev, whence the Hutterites transferred to the Molotschna settlement near Melitopol, establishing the villages of Huttertal, Johannesruh, Hutterdorf, and Neu-Huttertal. All the Hutterites immigrated to the United States in 1874-1877.

Period of Growth and Achievement (1850-1917)

The reason for the rapid spread of the Mennonite settlements in Russia was their increase in population. Ehrt comes to the conclusion that of the 120,000 Mennonites in Russia after World War I, 75,000 were found in the Ukraine and 45,000 in the other parts of Russia including Siberia. His analysis was based on the statistics of the AMLV. In 1926 there were 19,267 Mennonites living in Siberia, 1,545 in Turkestan, 4,017 in the Crimea, 3,246 at the foothills of the Caucasian Mountains, 7,596 in the province of Samara, 5,655 in the Volga region, and 2,175 scattered, or a total of 44,304 in the RSFSR (USSR outside of the Ukraine). His statistics, based on the official report of the KfK of 1926, give a total of 46,830 for the Ukraine, which makes the total of 91,134 in all USSR for the year 1926, in spite of the immigration of over 20,000 Mennonites to America 1922-1926 (Ehrt, 152 ff.).

What is the Mennonite population of Russia in the 1850s? No definite answer can be given to this question. However, here is an estimate. In 1920 the Mennonites of Russia had a population of about 120,000. Annually there was an increase of around 3,000. By 1929 Ehrt (159) estimates that there had been an increase of 20,700. However, a total of some 23,000 left for America (1923-1929), leaving a population of 117,800 in 1929. On this basis we could continue with the estimate that the population normally increased by 3,000 annually. During the years of exile and disrupted family life the increase declined and there may actually have been times when the loss, due to concentration camps, etc., was greater than the increase. In spite of the great loss during the exile and evacuation and the reduced increase because of the separation of the families and the emigration of some 12,000 to Canada and South America in connection with World War II, the total population of Mennonite descent, although many may have given up their identity in belief and culture, may possibly be estimated at about 100,000.

Hand in hand with the expansion of the population and the establishment of new settlements went the total economic development of the Mennonites of Russia. The improvement of agricultural machinery enabled the Mennonites to produce hardy winter wheat on a large scale. A prosperous milling industry and the establishment of many businesses enabled them to market their products. The Mennonites were by no means restricted to rural occupations. Towns like Chortitza, Alexandrovsk, Halbstadt, Berdyansk, Ekaterinoslav, and Millerovo had become centers of Mennonite industry. Of all the businesses and industries owned and operated by Mennonites before World War I, 30 per cent were located in Chortitza. Of the total production of agricultural machinery produced in the Ukraine, 10 per cent was produced in Mennonite factories, while of the total output in Russia, 6.2 per cent was produced in Mennonite factories. By 1914 the commercialized or capitalistic enterprises of the Mennonites of Russia in agriculture, industry, and business had grown considerably, consisting of one third of the total Mennonite capital investment. This means that two thirds still followed the traditional agricultural pattern with some additional small home industries, while one third had gone over to large-scale capitalistic enterprises. Only 2.8 per cent of the population were the bearers of this commercialized and capitalistic tendency, owning three fourths of the total Mennonite capital (Ehrt, 91-96). (See Agriculture Among the Mennonites of Russia, Business, and Industry.)

The general cultural achievement of the Mennonites ran parallel with their economic progress. Schools, hospitals, and other institutions designed for public service were established. Centers of cultural progress were found in Gnadenfeld, Orloff, and Halbstadt, all in the Molotschna; and in Chortitza. Progressive leadership in education and spiritual life broke the lethargy of the early days and ushered in a well-developed educational system which had been inaugurated by Johann Cornies before 1847. Among the pioneer educators were Tobias Voth, Heinrich Heese, Heinrich Franz I, and Fr. W. Lange. The first secondary schools (see Zentralschule) were established in Orloff, Gnadenfeld, and Chortitza. Various organizations promoted the educational institutions and standards among the Mennonites, particularly in the early days the Fürsorge-Komitee, the Agricultural Association, and the Molotschnaer Mennonitischer Schulrat.

Problems in connection with education arose when the Russianization policy of the government gradually subjected the Mennonite educational system to the Department of Education of Russia. This speeded up and reinforced the desire of many in the 1870's to immigrate to North America. All of the school subjects, with the exception of Bible and German literature, came gradually to be taught in the Russian language. In 1920 the Mennonites of Russia had about 450 elementary schools with about 16,000 pupils, and 27 secondary schools (Zentralschulen) with about 2,000 pupils and a teaching staff of 100.

With the Revolution of 1917 and the introduction of the antireligious Marxian philosophy in education, the Mennonite educational system was gradually wiped out. Many of the teachers immigrated to America, were exiled, or chose another vocation. Some adjusted themselves to the Soviet philosophy. The well-developed educational system produced by the Mennonites of Russia, which was not equaled anywhere else among Mennonites, disintegrated (see Education Among the Mennonites in Russia).

Religious life among the Mennonites of Russia was on a comparatively low plane at the outset. Leadership was lacking and had to be selected from an untrained constituency which at times also lacked spiritual qualities. Gradually, with the help of the mother church of Prussia, the church life was organized and made some progress. One of the earliest schisms took place when Klaas Reimer of the Molotschna, an ultraconservative leader, separated and organized the Kleine Gemeinde in 1814.

Progressive leadership and a more vital religious life came through some of the groups who immigrated to Russia later and established villages and congregations such as Gnadenfeld in the Molotschna. They introduced the practice of abstinence, mission festivals, and other pietistic and evangelistic views. Some of these Mennonites who came from Prussia had been in contact with the Moravian Brethren of Germany. Another source of influence came from Eduard Wüst, who was a Württemberg Pietist and the minister of an Evangelische Brüdergemeinde at Neuhoffnung near Berdyansk. He promoted evangelism, mission festivals, prayer meetings, etc. Some of the Mennonite leaders, e.g., Cornelius Jansen, Bernhard Harder, and August Lenzmann, were his personal friends. Soon his sermons were attended by Mennonites, and he was also at times invited to preach in the Mennonite villages. A strong emphasis on a personal acceptance of salvation and conversion was typical of his preaching. A group of eighteen heads of families in the village of Gnadenfeld who had been influenced by Wüst asked their elder August Lenzmann to administer the Lord's Supper to them as a special group. When he denied the request, this group of eighteen not only observed the Lord's Supper independently, but also drew up a document (6 January 1860) stating why they desired to start a new church. This act was the official founding of the Mennonite Brethren Church. Through the Baptists this group was further influenced in certain religious practices, e.g., the introduction of baptism by immersion. The struggle between this group and the leaders of the old church continued for a while, during which time both sides made mistakes and expressed more zeal than brotherly love. The new group was extreme in denouncing the church from which they had seceded, and some of the Mennonite leaders took an unbrotherly attitude toward the new group. Among those who did much to improve the relationship were Johann Harder, Bernhard Harder, and Leonhard Sudermann. These were the men who favored a more spontaneous expression of the joy of salvation and newer methods of promoting the Gospel, similar to the founders of the General Conference Mennonite Church which had originated slightly earlier in North America and was led by men like John Oberholtzer, Christian Schowalter, Daniel Hoch, and Daniel Hege.

The growth of the Mennonite Brethren group in Russia was notable. In 1888, 95.7 per cent of all Mennonites of Russia belonged to the Mennonite Church, while 4.3 per cent belonged to the Mennonite Brethren Church and other groups (Ehrt, 61). In 1925-1926 74.9 per cent belonged to the Mennonite Church while 22.5 per cent belonged to the Mennonite Brethren and 2.6 per cent to other groups. The growth of the Mennonite Brethren is particularly noticeable in the daughter settlements. In 1925-26, 81.2 per cent of the total Mennonite population of the Ukraine, in which the mother settlements were located, belonged to the Mennonite Church, 15.5 to the Mennonite Brethren, and 3.3 to other groups. In the RSFSR, that is, the rest of Russia outside of the Ukraine, consisting primarily of daughter settlements, the percentage differed considerably. To the Mennonite Church belonged 60.5 per cent, to the Mennonite Brethren 38.2 per cent, and to other groups 1.3 per cent. This makes it clear that the strongest increase in Mennonite Brethren, which was due primarily to winning members from the Mennonite Church, was found in the daughter settlements. It could also indicate that the Mennonite Brethren of the mother settlements were more active in the establishment of daughter settlements (Ehrt, 85).

Bible study, prayer meetings, song festivals, evangelistic meetings, publication efforts, conference organizations were among the results of this general spiritual revival, which gradually affected all the Mennonites of Russia. The Allgemeine Bundeskonferenz der Mennonitengemeinden in Russland, founded in 1883, was also attended from 1906 and officially from 1910 by the Mennonite Brethren, who had their own conference from 1872. Beginning in 1910 a Kommission für Kirchenangelegenheiten, usually called KfK, functioned as the executive committee of the Bundeskonferenz.

Other new groups which originated in Russia were the Krimmer Mennonite Brethren in 1869, the Mennonite section of the Temple Church or Friends of Jerusalem in 1863, the followers of Hermann Peters in 1866, and the Evangelische Mennoniten-Gemeinden in 1905. Another result of the general pietistic influence was the migration of Mennonites from the Molotschna and the Am Trakt under the leadership of Abraham Peters and Claas Epp to Central Asia in 1880 to avoid all military or alternative service and to meet the Lord at a designated place of refuge in the East.

Two of the most disturbing factors during the second half of the 19th century were the introduction of a universal military conscription law and the inauguration of a general program of Russianization of foreign settlers in Russia. They caused one third of all Mennonites of Russia to leave for the United States and Canada in 1874-1880. Only the compromise of the Russian government in granting the Mennonites the privilege of fulfilling their state obligations in forestry service prevented a more or less general exodus. Some 18,000 Mennonites went to North America, where the largest Mennonite settlements were established in Kansas and Manitoba. The Manitoba settlers were primarily from Chortitza, Fürstenland, and Bergthal, some of which became known as the Old Colony Mennonites, most of whom later went to Mexico because of their ultraconservative attitudes. The Mennonites settling in the United States were primarily those coming from the Molotschna settlement, Prussia, Russian Poland, and Galicia, including the Hutterites, most of whom went to Canada after 1918. The Mennonites remaining in Russia fulfilled their duty toward the government in forestry service and also in World War I in part in hospital service. Even under the Soviet government they were for a while exempted from military service; this privilege was rescinded ca. 1935.

At the beginning of the 20th century the need for educated ministers had grown to the extent that the advisability of establishing a theological seminary was repeatedly discussed. The same was true regarding the publication efforts. The anti-German feeling of the Russian government was not conducive to the promotion of these plans. Young men received their education more and more in Germany and Switzerland at Bible schools, theological seminaries, and universities. Some studied at Russian universities. Semiofficial periodicals such as the Botschafter and the Friedensstimme and almanacs served the constituency after 1903-1905 with interruptions.

Under Communism (1917-1957)

The overthrow of the Tsarist government, the Civil War, and the ultimate establishment of the Communist regime starting in October 1917 caused most radical changes for the Mennonites of Russia. The first period was characterized by the Civil War, confiscation and nationalization of property, starvation, and general confusion, which ended with the full working establishment of the Communist government.

The Mennonite way of life was undermined in its basis by laws like the following issued 8 April 1929: "Religious organizations are forbidden to (a) organize mutual aid and co-operatives; (b) give material support to church members; (c) organize special meetings for children, youth, women, and prayer, and other meetings as well as general Bible literature, sewing societies, work groups and religious instruction groups, circles, and arrange for excursions and entertainment for children, for libraries and reading materials, and to organize hospitals and medical aid."

At the General Conference meeting of the Mennonites of Russia which took place in Moscow in January 1925, the following eight points were stated as the minimum requirement for the Mennonites to survive: (1) undisturbed religious meetings and discussions in church and private homes for adults and children; (2) undisturbed religious societies, choirs, instruction in religion and doctrines especially for children and youth; (3) undisturbed founding of Mennonite orphanages with Christian education; (4) undisturbed erection of new church buildings and the exemption of church and ministers from special taxes; (5) undisturbed acquisition of Bibles and aids and other Christian literature including periodicals for the congregations; (6) undisturbed Bible courses conducted for the preparation and the deepening of the knowledge of ministers; (7) recognition of the schools as a neutral territory where neither religious nor antireligious propaganda takes place and where exclusively knowledge is taught by teachers who have freedom in their private life; (8) exemption from military service and basic military preparation, the granting of a useful alternative service, and exemption from the oath for Mennonites who make a simple promise. A conference resolution made the following assertion: "These eight points of the KfK in the memorandum to the Central Executive Committee of the USSR regarding the fundamental questions of Mennonite church life the meeting considers the minimum prerequisite for the continued existence of the Mennonites as a religious fellowship." This request was declined, but the conference appealed again to the government on 16 January 1925, the petition closing with these words, "Give us our children, give us freedom to train and educate them in accord with the commands of our conscience" (Ehrt, p. 141 f.). These were some of the last organized efforts of the Mennonites of Russia to obtain rights to continue their religious life in accord with their basic beliefs.

At this time (1922-1927) some 23,000 Mennonites left Russia since they saw no hope for a better future. Exemption from military service was still possible for a time, possibly until 1930-1935. Each individual had to apply for exemption and each case was separately examined by a court. The questions which the court decided were whether the religious group to which the applicant belonged actually were conscientious objectors, and whether the applicant actually believed and lived in accord with this tradition. If he was exempted, he could do alternative service. The Soviet law made ample provision for exemption from military service, which other groups besides Mennonites, such as the Dukhobors, followers of Tolstoy, and Baptists made use of. However, soon the practice was found to be in conflict with the original democratic theory. Ehrt reports that of 131 young Mennonites who applied for exemption in 1925, only 64 were freed, 20 accepted full military service, and 47 were imprisoned. Of 22 young men imprisoned in the Caucasus area, four died of typhoid fever and 14 were shot. In 1926 there were 70 Mennonite young men imprisoned in Kiev who were to be sent to forced labor camps because of their objecting to military service (Ehrt, 143 ff). The alternative service camps resembled slave labor camps in severity of treatment and difficulty of physical survival. In the beginning of the 1930's it became almost impossible to be exempted from military service. Gradually young men were forced to serve in the regular army. No organized spiritual fellowship was possible since the leaders and the ministers had been exiled. Whether and to what an extent some of the young men refused in these years to serve in the army was not known in the 1950s. When Hitler invaded the Ukraine, a systematic effort was made to remove from the Red army all people of German background including the Mennonites, although some remained in the army in spite of this effort.

Stalin's harsh program of collectivization and exile caused some 13,000, not all Mennonites, to flee to Moscow in 1929, of whom only some 5,000 were permitted to leave, settling mostly in Brazil and Paraguay, although perhaps 1,000 got to Canada. The ruthless destruction of the Mennonite religious and cultural life was a part of the total program of dictatorship, through which many families were disrupted by exile and death, particularly among the leaders such as ministers and teachers.

With the outbreak of hostilities between Russia and Germany in 1941, an attempt was made to send eastward the remaining German-speaking males west of the Volga, including Mennonites. When the German army invaded the Ukraine, an attempt was made to move all the Mennonites (Germans) of the Ukraine to the east of the Dniepr River. This attempt was only partially successful. Most of the Chortitza Mennonites remained in German-occupied territory. During this time the cultural and religious life was restored to some extent but only for a short time (1941-1943), and some of the churches were again being closed. When the German front collapsed in Russia and the retreat began, the remaining Mennonite population of the Ukraine was evacuated by the retreating German army by trains or wagon caravans starting in the fall of 1943 with the goal of settling them in the Warthegau, former western Poland, along the Vistula River, near the general area where they had come from 150 years before. With the collapse of Hitler's empire, these Mennonites fled westward; one third ultimately reached Canada and South America; the majority, however, were returned to Russia and only a very few remained in Germany. It is estimated that some 35,000 Mennonites were taken along to Germany by the German army in 1943, of whom nearly two thirds were forcibly repatriated by the Red army, while one third or some 12,000 went to Canada and Paraguay, where they established the Volendam and Neuland settlements. Meanwhile many have left South America and joined their relatives in Canada. Many of the Russian Mennonite men were drafted into the German army in 1941-1945. Practically all the Russian Mennonites in the Warthegau, together with other Russian Germans, were naturalized en masse by the German authorities in 1943.

After the death of Stalin in 1953, conditions in Russia somewhat changed. The picture became clearer as to what happened to those Mennonites who remained in Russia and those who were sent back to Russia from Germany. The original assumption that the Chortitza and Molotschna settlements as well as the daughter settlements of the Ukraine were severely damaged and that no Mennonites remained there proved correct. But there were some indications that a few families returned after Stalin's death, since there was greater freedom for the civilians to move about. In some of the settlements east of the Volga like Orenburg, Pleshanovo, and particularly in Siberia, large numbers were allowed to remain in their original homes. To some extent they retained some phases of their cultural and religious life, which was illustrated by the fact that conversions and baptismal and worship services have taken place quite regularly in the 1950s. A large concentration of the exiled, evacuated, and uprooted Mennonites was noticeable in the Asiatic Russian regions and territories immediately east of the Ural Mountains in Soviet Central Asia, especially Kazakh S.S.R. etc., and Siberia. The old Mennonite settlements of Slavgorod, Omsk, and Pavlodar have been relatively undisturbed as geographic units. Karaganda has become the center of a large congregation. The settlements in Old and New Samara and the Caucasus were also completely destroyed.

It can be estimated that Russia again had a total of 100,000 Mennonites at the time when Hitler invaded the Ukraine (1941) in spite of the fact that some 25,000 had migrated to America. Of these 100,000 probably one fifth was exiled under Stalin, and one fourth was evacuated eastward when the German army invaded Russia in 1941. This would mean that 45,000 of the 100,000 Mennonites were either in forced labor camps or evacuated to uninhabited places by the time of the outbreak of World War II in Russia. There were still some 35,000 Mennonites left in the Ukraine who were taken along by the German army in 1943. Of these some 23,000 were repatriated and sent to uninhabited places, primarily to Asiatic Russia. This would indicate that of the ca. 100,000 Mennonites living in Russia in the 1950s, only some 30,000 lived in their former home communities; the majority were scattered all over the Ural region and farther east. Many of them spent ten to twenty years in labor or concentration camps.

Typical of the number of people exiled was the Chortitza Mennonite settlement. In 1929-1941, 1,456 Mennonites of the total population of 13,965 were exiled. The worst years were 1929-1930 and 1937-1938. In 1929, 153 were exiled; in 1930, 244; in 1937, 361; and in 1938, 465. Of the 1,456, 1,148 were men, 43 were women, and 44 were young people. It is not known where 973 of them were sent. Six were sent to the Far East, 18 to Siberia, 332 to the Ural Mountains, 4 to Kazakhstan, 66 to the northern parts of European Russia, 6 to Central Russia, and 57 to Southern Russia (Stumpp).

These camps were scattered all over European and Asiatic Russia. Dallin and Nicolaevsky listed 125 camps or clusters of camps while B. Yakovlev listed 165, some of which were clusters of camps. Both sources stated that their lists were incomplete. There was hardly a part of Russia which did not have camps. Dallin and Nicolaevsky subdivided the camps according to geographic location and listed 58 camps in European Russia, many of which were located in the northern region. In Asiatic Russia they listed 67 camps located in western, northern, and eastern Siberia, and Central Asia. Since the days when Stalin developed these labor camps, some changes have taken place. Many of the camps have been closed. In the 1950s those who had served their terms in camps or had been forcibly settled at places obtained greater liberties to move about. On the other hand, it was clear that Nikita Khrushchev placed great emphasis on settling uninhabited places in Asiatic Russia. Of particular interest to him was the Kazakh S.S.R. (Kazakhstan) in Soviet Central Asia, where a great increase in population was reported. Many people settled here "voluntarily." It became apparent that many of the Mennonites were now located in the Kazakh S.S.R. and other parts of Soviet Central Asia. No doubt many were sent there when they were repatriated, others were exiled into that region, still others may have been attracted to this area because of the concentration of Mennonites there. It can be assumed that of the Mennonites in the U.S.S.R. in the 1950s, some 80 per cent were located east of the Ural Mountains and some 20 per cent in European Russia, of whom only a small number were found in the old Mennonite settlements such as Orenburg and Pleshanovo. The number of Mennonites living in their original settlements in the 1950s could be estimated as follows: Orenburg settlement, 5,000 (Europe); Pleshanovo settlement, 2,500 (Europe); Slavgorod settlement, 14,000 (Siberia); Omsk settlement, 4,000 (Siberia); Pavlodar settlement, 2,500 (Siberia), and Amur settlement, 2,000 (Siberia). This made an estimated total of 30,000. Of these, only some 7,500 lived in European Russia.

To what extent a concentration of Mennonites in these old and new settlements in Asiatic Russia and a revival of religious and cultural traditions through an organized program will be possible depends very much on the development of civil and religious freedom in Soviet Russia, including the rights for minority groups. Being of Germanic background and of a group with deep religious motivations, resisting the antireligious Marxist philosophy of life, the Mennonites as some other minority groups of Russia were distrusted and uprooted before and during World War II. Now that they have lost their religio-cultural foundation and stronghold in the Ukraine, a perpetuation of their cultural values, which were based on their settlements and educational system, may be extremely difficult. Even if greater freedom is granted to them, an adjustment to their Russian environment including intermarriage and the rapid loss of the German language is unavoidable unless a radical change takes place. Of course, a strong Christian faith and church life can be built without the German language and culture. The very changeover to the Russian language may be the door to a much wider and more effective Mennonite witness in Russia.

Looking over the 150 years that Mennonites lived in Russia, it can be said that they had unparalleled opportunities for establishing and maintaining communities on the basis of their understanding of Biblical truth and their heritage. They carried out the mission for which they were called; namely, to transform barren steppes into a garden spot and granary of Russia and to show the surrounding Slavic and nomadic population an exemplary Christian life in family and community and model methods of tilling the soil. Men like Johann Cornies and the settlements as a whole had a great influence on the surrounding population. But this influence was not restricted to the economic and social life. The Evangelical movement of Russia was influenced strongly by the Mennonites for nearly a century. This contact continued even in the 1950s. The Mennonites of Russia had an opportunity for a self-realization and witness which they discharged with great success. (See "Russian Baptists and Mennonites," Mennonite Life, July 1956, 99). -- Cornelius Krahn

1990 Update

In the late 20th century the focus of Soviet Mennonite activity shifted from the Ukraine to the RSFSR (now Russia), an administrative unit that covered three fourths of all Soviet territory and contained half the population of the USSR. Following the liquidation of the settlements in the Ukraine (1943) what remained as Mennonite settlement areas were the Orenburg settlements (formerly the Samara and Am Trakt settlements), a chain of villages along a railroad line from Omsk to Novosibirsk, and extensive settlements of Mennonites in the Altai region of Western Siberia, including such cities as Slavgorod, Pavlodar, and Barnaul. All of these areas received more Mennonites through the forcible repatriation of refugees after World War II and Deportation Regime (Spetskomandantura).

Repatriated Germans including Mennonites were sent into the forests northeast of Moscow, especially in Vologodskaia, Permskaia, Arkhangel'skaia Oblasts (provinces of the RSFSR) and in the Karelian and Komi Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republics (ASSRs). These included such places as Vologda, Sokol, Arkhangel'sk Syktyvkar, Ukhta, Krasnovishersk, Solikamsk, Perm, Sverdlovsk, Novaiia Lialia, Krasnoturinsk, Severoural'sk, Cheliabinsk. These names signify hardship and became the grave for loved ones. Many of these settlements were abandoned when the Deportation Regime was lifted (after 1955) as Mennonites moved farther south into the industrial cities in the Ural mountain range and still farther to northeastern Kazakhstan where relatives had been sent to work in the mines. The Karaganda region of Kazakhstan is now (1988) the largest center for Mennonites in the USSR. Many others moved in the early 1960s to southern Kazakhstan (Alma Ata) or nearby Kirgizia.

In the RSFSR (Russia) the Novosibirsk Kirchliche Mennonite congregation had been functioning openly since 1960 but was only registered in 1973. By that date a few congregations of Mennonite Brethren (MB) and Kirchliche Mennonites were functioning in the Orenburg settlements, but the Donskoi church (MB) was the first to be registered in 1978. In 1988 there were 31 registered congregations in Orenburg Oblast, of which 6 belonged to the All-Union Council of Evangelical Christians - Baptists (AUCECB), 14 were Mennonite Brethren, and 11 were Kirchliche Mennonites, representing about 3,000 and 750 members for the latter two groups. Little was known about congregations in the Altai region.

Revival came to isolated settlements when preachers of the gospel, often just released from prison, came by, sometimes also performing baptisms for dozens at a time. Such heroes, most of them still unnamed, braved the elements and the long arm of the law as they sought to encourage lonely, isolated Mennonite people. Others came to rely on shortwave radio broadcasts. A meeting of Kirchliche Mennonite elders and preachers in 1957 in Solikamsk (northern Urals) to organize a conference was broken up by the authorities. There is still no system of regular communication for either Mennonite Brethren or Kirchliche Mennonites. In 1979, the AUCECB organized a centralized senior presbyter structure for the RSFSR, naming Jakob Fast as one of two deputy senior presbyters, with special duties to visit Mennonite congregations in the RSFSR. -- Walter W. Sawatsky

2011 Update

The following table summarizes the number of Mennonites in Russia between 2000 and 2012:

| Membership in 2000 |

Membership in 2003 |

Membership in 2006 |

Membership in 2009 |

Membership in 2012 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

3,350

|

5,000

|

3,000

|

3,000

|

3,000

|

Bibliography

Introduction

This is a selected bibliography. For a complete list of books and periodicals (1950s), see the bibliographies of the dissertations by Adolf Ehrt and David G. Rempel. For additional information see also the various articles dealing with settlement and institutions of Russia.

General

Auhagen, Otto. Die Schicksalswende des russlanddeutschen Bauerntums in den Jahren 1927-1930. Leipzig, 1942.

Bonwetsch, G. Geschichte der deutschen Kolonien an der Wolga. Stuttgart, 1919.

Dallin, David J. and B. L. Nicolaevsky. Forced Labor in Soviet Russia. New Haven, 1947.

Hume, George. Thirty-Five Years in Russia. London, 1914.

König, Lothar. Die Deutschtumsinsel an der Wolga. Dülmen, 1938.

Kulischer, Eugene M. Europe on the Move: War and Population Changes in 1917-97. New York, 1948.

Leibbrandt, Sammlung Georg. Die deutschen Siedlungen in der Sowjetunion. Berlin, 1941.

Lindemann, Karl. Von den deutschen Kolonisten in Russland. Ergebnisse einer Studienreise 1919-21. Stuttgart, 1924.

Manning, Clarence A. The Story of the Ukraine. New York, 1947.

Matthaei, Friedrich. Die deutschen Kolonisten in Russland. Leipzig, 1866: 389.

Mennonite World Conference. "2000 Europe Mennonite & Brethren in Christ Churches." Web. 27 February 2011. http://www.mwc-cmm.org/Directory/2000europe.html.

Mennonite World Conference. "2003 Europe Mennonite & Brethren in Christ Churches." Web. 27 February 2011. http://www.mwc-cmm.org/Directory/2003europe.html.

Mennonite World Conference. "Europe." Web. 27 February 2011. http://www.mwc-cmm.org/Directory/2006europe.pdf.

Mennonite World Conference. "World Directory: Europe." Web. 27 February 2011. http://www.mwc-cmm.org/en15/files/Members2009/EuropeSummary.doc.

Mennonite World Conference. World Directory = Directorio mundial = Répertoire mondial 2012: Mennonite, Brethren in Christ and Related Churches = Iglesias Menonitas, de los Hermanos en Cristo y afines = Églises Mennonites, Frères en Christ et Apparentées.Kitchener, ON: Mennonite World Conference, 2012: 16.

Mundt, Theodor. Kampf um das Schwarze Meer. Braunschweig, 1855.

Petzholdt, Alexander. Reise im westlichen und südlichen europdischen Russland im Jahre 1855. Leipzig, 1864: Ukraine mit Krim, Part 3, Dongebiet und Kaukasus, Part 4.

Pisarevskij, G. Iz istorrii innostranoj kolonizacii v Rossii v XVIII v. Moskva 1909: Iz V T., Zapisok Mosk. Archeologiceskogo Instituta 1909.

Stumpp, K. Die deutschen Kolonien im Schwarzmeergebiet, dem früheren Neu- (Süd-) Russland. Ein siedlungs- und wirtschaf tsgeographischer Versuch. Stuttgart, 1922.

Der Wanderweg der Russlanddeutschen. Stuttgart, 1939.

Yakovlev, B. Concentration Camps in the USSR (Russian). Munich, 1955.

Periodicals

Der Bote (Rosthern, SK 1924- ).

Der Botschafter (Ekaterinoslav, 1905-1914).

Christlicher Familien-Kalender, ed. A. Kröker (Halbstadt, 1897-1919).

Friedensstimme (Halbstadt, 1903-1914).

Mennonite Life (North Newton, 1946- ).

Mennonitische Rundschau (1877- ,Winnipeg, 1924- ).

Mennonitisches Jahrbuch, ed. Heinrich Dirks (Gross-Tokmak, 1901-14).

Mennonitisches Jahrbuch, ed. Cornelius Krahn (Newton, KS 1948- ).

Der praktische Landwirt (Moscow, 1925-28).

Unser Blatt (Grossweide, 1925-28).

Books and Articles Specifically on Mennonites

Bondar, S. D. Sekta Mennonitov v Rossii. Petrograd, 1916.

Dyck, J. J. Am Trakt. North Kildonan, 1948.

Ehrt, Adolf. Das Mennonitentum in Russland . . . Berlin, 1932.

Eisenbach, George J. Pietism and the Russian Germans in the United States. Berne, 1948.

Epp, D. H. Die Chortitzer Mennoniten. Versuch einer Darstellung des Entwicklungsganges derselben. Rosental, 1889.

Epp, David H. Heinrich Heese and Nikolai Regehr, Johann Philipp Wiebe. Steinbach, 1952.

Epp, David H. Johann Cornies. Berdyansk, 1909 and Rosthern, 1956.

Fast, Gerhard. "The Mennonites under Stalin and Hitler." Mennonite Life 2 (April 1947): 18 ff.

Friesen, Peter M. Die Alt-Evangelische Mennonitische Brüderschaft in Russland (1789-1910) im Rahmen der mennonitischen Gesamtgeschichte. Halbstadt: Verlagsgesellschaft "Raduga", 1911.

Froese, Leonhard. Das pädagogische Kultursystem der mennonitischen Siedlungsgruppe in Russland. Göttingen, 1949.

Goerz, H. Memrik. Rosthern, 1952.

Görz, H. Die Molotschnaer Ansiedlung. Entstehung, Entwicklung und Untergang. Steinbach, 1950.

Gutsche, Waldemar. Westliche Quellen des russischen Stundismus. Kassel, 1956.

Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. Mennonitisches Lexikon, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. III, 573-581.

Hiebert, P. C. and Orie O. Miller. Feeding the Hungry, Russia Famine 1919-1925. Scottdale, 1929.

Hildebrand, J. Sibirien. Winnipeg, 1952.

Hildebrandt, P. Erste Auswanderung der Mennoniten aus dem Danziger Gebiet nach Südrussland. Halbstadt, 1888.

Isaac, Franz. Die Molotschnaer Mennoniten. Halbstadt, 1908.

Jahresbericht des Bevollmächtigten der Mennonitengemeinden in Russland in Sachen der Unterhaltung der Forstkommandos. Jahre 1908.

Klaus, A. Unsere Kolonien. Odessa, 1887.

Kröker, Abr. and Pfarrer Eduard Wüst. Der grosse Erweckungsprediger in den deutschen Kolonien Südrusslands. Leipzig, 1903.

Die Kubaner Ansiedlung. Steinbach, 1953.

Lohrenz, Gerhard. Sagradowka. Rosthern, 1947.

Lohrenz, J. H. The Mennonite Brethren Church. Hillsboro, 1950.

Mannhardt, H. G. Die Danziger Mennonitengemeinde. Ihre Entstehung und ihre Geschichte von 1569 bis 1919. Danzig, 1919.

Mannhardt, W. Die Wehrfreiheit der Altpreussischen Mennoniten. Marienburg, 1863.

Die Mennoniten-Gemeinden in Russland während der Kriegs- und Revolutionsjahre 1914-1920. Heilbronn, 1921.

Quiring, Horst. "Die Auswanderung der Mennoniten aus Preussen 1788-1870." Mennonite Life 6 (April 1951).

Quiring, J. Die Mundart von Chortitza in Süd-Russland. Munich, 1928.

Reimer, Gustav E. and G. R. Gaeddert. Exiled by the Czar. Newton, 1956.

Rempel, David G. "The Mennonite Colonies in New Russia. . . " Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Stanford University, 1933.

Schrag, Martin H. "European History of the Swiss-Volhynian Mennonite Ancestors of Mennonites now Living in Communities in Kansas and South Dakota." Unpublished M.A. thesis, Eastern Baptist Theological Seminary, May 1956.

Schröder, Heinrich H. Russlanddeutsche Friesen. Döllstadt, 1936.

Smith, C. Henry. The Coming of the Russian Mennonites. Berne, IN, 1927.

Smith, C. Henry The Story of the Mennonites. Newton, KS, 1957.

Toews, Cornelius P. Die Tereker Ansiedlung. Rosthern, 1945.

Töws, A. A. Mennonitische Märtyrer I and II. North Clearbrook, 1949, 1954.

Unruh, A. H. Die Geschichte der Mennoniten Brüdergemeinde. Winnipeg, 1954.

Unruh, Benjamin H. Die niederländisch-niederdeutschen Hintergründe der mennonitischen Ostwanderungen im 16., 18. und 19. Jahrhundert. Karlsruhe, 1955.

1990 Update

Pipes, Richard. The Formation of the Soviet Union. Revised edition. New York: Atheneum, 1964.

Sawatsky, Walter. "Mennonite Congregations in the Soviet Union Today." Mennonite Life 33 (March 1978): 12-26.

Sawatsky, Walter. "From Russian to Soviet Mennonites 1945-1985." In Mennonites in Russia, 1788-1988: Essays in Honour of Gerhard Lohrenz, edited by John J. Friesen. Winnipeg, MB: CMBC Publications, 1989.

Stricker, Gerd. "Mennoniten in der Sowjetunion nach 1941." Kirche im Osten, 27 (1984).

| Author(s) | Cornelius Krahn |

|---|---|

| Walter W. Sawatsky | |

| Date Published | February 2011 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Krahn, Cornelius and Walter W. Sawatsky. "Russia." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. February 2011. Web. 16 Apr 2024. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Russia&oldid=146175.

APA style

Krahn, Cornelius and Walter W. Sawatsky. (February 2011). Russia. Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 16 April 2024, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Russia&oldid=146175.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 4, pp. 381-393, 1148; vol. 5, pp. 782-783. All rights reserved.

©1996-2024 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.