Difference between revisions of "Servetus, Michael (1511-1553)"

| [checked revision] | [checked revision] |

GameoAdmin (talk | contribs) (CSV import - 20130823) |

m (Text replace - "<em>Mennonitisches Lexikon</em>, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. IV," to "''Mennonitisches Lexikon'', 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. IV,") |

||

| (3 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

The second new element was the Neoplatonism of the Florentine academy with which he became acquainted through the medical humanists of France. In accord with this tradition he interpreted Christ to be the light of the world in terms of the metaphysics of light. Servetus was not a systematic thinker. His writing is marked by bold speculation and by passionate outbursts of lyrical piety. | The second new element was the Neoplatonism of the Florentine academy with which he became acquainted through the medical humanists of France. In accord with this tradition he interpreted Christ to be the light of the world in terms of the metaphysics of light. Servetus was not a systematic thinker. His writing is marked by bold speculation and by passionate outbursts of lyrical piety. | ||

| − | Through channels unknown to us the full circumstances of Servetus' identity and of the publication of his book came to be known in Geneva and were brought to the attention of [[Calvin, John (1509-1564)|John Calvin ]]with whom Servetus some time previously had carried on an exacerbated correspondence. A certain Guillaume Trie, a Protestant of Geneva, had betrayed Servetus to the Inquisition at Vienne and then, being challenged for evidence, inveigled Calvin into supplying the necessary documentation. Servetus escaped, however, from the prison of the Inquisition and after wandering for three months turned up in Geneva on 13 August 1553. | + | Through channels unknown to us the full circumstances of Servetus' identity and of the publication of his book came to be known in Geneva and were brought to the attention of [[Calvin, John (1509-1564)|John Calvin]] with whom Servetus some time previously had carried on an exacerbated correspondence. A certain Guillaume Trie, a Protestant of Geneva, had betrayed Servetus to the Inquisition at Vienne and then, being challenged for evidence, inveigled Calvin into supplying the necessary documentation. Servetus escaped, however, from the prison of the Inquisition and after wandering for three months turned up in Geneva on 13 August 1553. |

There he was recognized and was denounced to the Town Council on the capital charge of heresy at the instance of John Calvin. After a trial of two months Servetus was condemned as guilty of the two religious crimes subject to death in the code of Justinian, namely, the repetition of baptism and the denial of the Trinity. He was sentenced to be burned at the stake. Servetus petitioned for death by the sword lest he recant and lose his soul. Calvin seconded his request, but it was denied by the Council. From the flames Servetus called upon "Christ, the Son of the eternal God." Had he been willing to shift the position of the adjective and call upon "Christ, the eternal Son," he might have been saved. The <em>Restitutio Christianismi </em>was so effectively suppressed that only three copies survive, though there is an 18th-century reprint. | There he was recognized and was denounced to the Town Council on the capital charge of heresy at the instance of John Calvin. After a trial of two months Servetus was condemned as guilty of the two religious crimes subject to death in the code of Justinian, namely, the repetition of baptism and the denial of the Trinity. He was sentenced to be burned at the stake. Servetus petitioned for death by the sword lest he recant and lose his soul. Calvin seconded his request, but it was denied by the Council. From the flames Servetus called upon "Christ, the Son of the eternal God." Had he been willing to shift the position of the adjective and call upon "Christ, the eternal Son," he might have been saved. The <em>Restitutio Christianismi </em>was so effectively suppressed that only three copies survive, though there is an 18th-century reprint. | ||

| − | The execution on 27 October 1553, marked the beginning of the toleration controversy on an extensive scale in Protestant churches. The reformers of the established Protestant churches endorsed the action of the Geneva Town Council and of Calvin, for example, [[Melanchthon, Philipp (1497-1560)|Melanchthon]] and [[Brenz, Johannes (1499-1570)|Brenz]]. (Luther was dead.) But many were deeply troubled. Vergerio was aghast. [[David Joris (ca. 1501-1556)|David Joris ]]entered a plea for the accused during the trial. [[Zell, Katharina (16th century)|Catherine Zell]], Postell, and Curio voiced disapproval. The most influential protest was that of [[Castellion, Sébastien (1515-1563)|Castellio]] | + | The execution on 27 October 1553, marked the beginning of the toleration controversy on an extensive scale in Protestant churches. The reformers of the established Protestant churches endorsed the action of the Geneva Town Council and of Calvin, for example, [[Melanchthon, Philipp (1497-1560)|Melanchthon]] and [[Brenz, Johannes (1499-1570)|Brenz]]. (Luther was dead.) But many were deeply troubled. Vergerio was aghast. [[David Joris (ca. 1501-1556)|David Joris]] entered a plea for the accused during the trial. [[Zell, Katharina (16th century)|Catherine Zell]], Postell, and Curio voiced disapproval. The most influential protest was that of [[Castellion, Sébastien (1515-1563)|Castellio]] in his <em>De Haereticis </em>(1554, actually printed at Basel). |

= Bibliography = | = Bibliography = | ||

Bainton, R. H. <em>Hunted Heretic. </em>Boston, 1953. | Bainton, R. H. <em>Hunted Heretic. </em>Boston, 1953. | ||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

Becker, B. <em>et al., Autour de Michel Servet et de Seb. Castellion. </em>Haarlem, 1953. | Becker, B. <em>et al., Autour de Michel Servet et de Seb. Castellion. </em>Haarlem, 1953. | ||

| − | Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. | + | Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. ''Mennonitisches Lexikon'', 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. IV, 155-156. |

Köhler, W. <em>Reformation und Ketzerprozess. </em>Tübingen, 1901. | Köhler, W. <em>Reformation und Ketzerprozess. </em>Tübingen, 1901. | ||

Latest revision as of 06:58, 16 January 2017

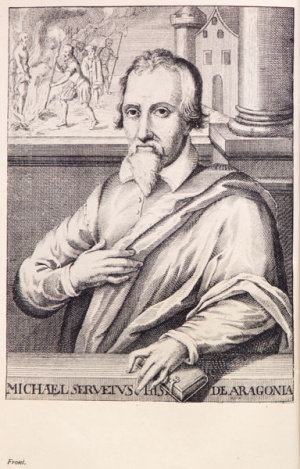

Michael Servetus, (1511-1553) a native of Spain, was much exercised over the problem of the conversion of the Jews and the Moors. The great obstacle appeared to him to be the requirement of belief in the doctrine of the Trinity. Great was his relief to discover that the technical language of that doctrine is not to be found in the New Testament. At the same time he learned from the Occamist theologians how many logical contradictions the doctrine entails. He concluded that the formulation of the essentials of the doctrine at the council of Nicaea constituted the fall in the history of the Church. His own view affirmed one God, operative through His Word, which is co-eternal with Himself and His agent in creation. This Word was united with the man Jesus, born of a virgin, to become the Son of God, who thus had a beginning in time and was not co-eternal with God. The term "Christ" was applied to the Word, whether before or after the incarnation. This doctrinal position was set forth by Servetus in his De Trinitatis Erroribus printed at Hagenow near Strasbourg, and thus on Protestant soil, in 1531 (English translation by E. Morse Wilbur, Harvard Theological Studies XVI, 1932). The work, issued before the censors were alerted, received a wide dissemination and exerted a marked influence upon the anti-Trinitarians.

By reason of this book Servetus was safe neither in Protestant nor in Catholic territory. He took refuge under pseudonymity and lived as Michel de Villeneuve in France, where for several years he supported himself as an editor. Everything he did gave offense. An edition of the Bible had notes which said that the prophets of the Old Testament were referring to events of their own times and were not predicting the future. An edition of Ptolemy's geography contained a passage denying that Palestine was a land flowing with milk and honey. Servetus then studied medicine in Paris and became the discoverer of the pulmonary circulation of the blood. For twelve years he practiced as a physician at Vienne near Lyons.

In 1553 he brought out clandestinely his great work, the Restitutio Christianismi, which repeated the views of the De Trinitatis Erroribus with the addition of two new elements. The first was Anabaptism which he had presumably imbibed during his previous stay at Strasbourg. With vehemence he denied the rightfulness of infant baptism, and recommended the postponement of baptism to the thirtieth year in imitation of Christ. The very title of the book, the Restitution of Christianity, is reminiscent of several Anabaptist works and the idea is precisely the Anabaptist ideal of the restoration of primitive Christianity. With the chiliastic Anabaptists he looked for the speedy return of the Lord and assigned to himself some ill-defined messianic role in that Michael Servetus would assist the archangel Michael. But Servetus was not an Anabaptist in his view of the church, which he held to be only a spiritual fellowship, nor in his conduct, since as a Nicodemite he attended mass.

The second new element was the Neoplatonism of the Florentine academy with which he became acquainted through the medical humanists of France. In accord with this tradition he interpreted Christ to be the light of the world in terms of the metaphysics of light. Servetus was not a systematic thinker. His writing is marked by bold speculation and by passionate outbursts of lyrical piety.

Through channels unknown to us the full circumstances of Servetus' identity and of the publication of his book came to be known in Geneva and were brought to the attention of John Calvin with whom Servetus some time previously had carried on an exacerbated correspondence. A certain Guillaume Trie, a Protestant of Geneva, had betrayed Servetus to the Inquisition at Vienne and then, being challenged for evidence, inveigled Calvin into supplying the necessary documentation. Servetus escaped, however, from the prison of the Inquisition and after wandering for three months turned up in Geneva on 13 August 1553.

There he was recognized and was denounced to the Town Council on the capital charge of heresy at the instance of John Calvin. After a trial of two months Servetus was condemned as guilty of the two religious crimes subject to death in the code of Justinian, namely, the repetition of baptism and the denial of the Trinity. He was sentenced to be burned at the stake. Servetus petitioned for death by the sword lest he recant and lose his soul. Calvin seconded his request, but it was denied by the Council. From the flames Servetus called upon "Christ, the Son of the eternal God." Had he been willing to shift the position of the adjective and call upon "Christ, the eternal Son," he might have been saved. The Restitutio Christianismi was so effectively suppressed that only three copies survive, though there is an 18th-century reprint.

The execution on 27 October 1553, marked the beginning of the toleration controversy on an extensive scale in Protestant churches. The reformers of the established Protestant churches endorsed the action of the Geneva Town Council and of Calvin, for example, Melanchthon and Brenz. (Luther was dead.) But many were deeply troubled. Vergerio was aghast. David Joris entered a plea for the accused during the trial. Catherine Zell, Postell, and Curio voiced disapproval. The most influential protest was that of Castellio in his De Haereticis (1554, actually printed at Basel).

Bibliography

Bainton, R. H. Hunted Heretic. Boston, 1953.

Becker, B. et al., Autour de Michel Servet et de Seb. Castellion. Haarlem, 1953.

Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. Mennonitisches Lexikon, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. IV, 155-156.

Köhler, W. Reformation und Ketzerprozess. Tübingen, 1901.

Woude, van der S. Verguisd Geloof. Delft, 1953: 49-144.

| Author(s) | Roland H Bainton |

|---|---|

| Date Published | 1959 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Bainton, Roland H. "Servetus, Michael (1511-1553)." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1959. Web. 18 Apr 2024. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Servetus,_Michael_(1511-1553)&oldid=146240.

APA style

Bainton, Roland H. (1959). Servetus, Michael (1511-1553). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 18 April 2024, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Servetus,_Michael_(1511-1553)&oldid=146240.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 4, pp. 506-507. All rights reserved.

©1996-2024 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.