Difference between revisions of "Switzerland"

| [checked revision] | [checked revision] |

m (→Bibliography) |

m (Text replace - "<em>Mennonitisches Lexikon</em>, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. IV," to "''Mennonitisches Lexikon'', 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. IV,") |

||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

Nevertheless the Swiss Brethren continued to increase in Switzerland. At the sessions of the federal parliament in Baden in January 1530, the Anabaptist question was again under discussion. The Protestant towns, Zürich, Bern, Basel, St. Gall, and Constance, united to adopt a common policy against the Anabaptists, because the "confused, miserable sect of the Anabaptists with their rabble and their doctrine are becoming everywhere more numerous and more dangerous, whereby in all true Christian faith great defection and division, much misery, shedding of blood and unrest results." | Nevertheless the Swiss Brethren continued to increase in Switzerland. At the sessions of the federal parliament in Baden in January 1530, the Anabaptist question was again under discussion. The Protestant towns, Zürich, Bern, Basel, St. Gall, and Constance, united to adopt a common policy against the Anabaptists, because the "confused, miserable sect of the Anabaptists with their rabble and their doctrine are becoming everywhere more numerous and more dangerous, whereby in all true Christian faith great defection and division, much misery, shedding of blood and unrest results." | ||

| − | Much misery and shedding of blood did indeed result from it, but not because of the faith of the Swiss Brethren, but because of the intolerant attitude of the government. It was actually the Protestant estates who insisted on it under the influence of the clergy. The Protestant cantons were very serious in their threat of making Anabaptism a capital crime. The bloody drama begun with Felix Manz in Zürich was continued in other Swiss cities. The | + | Much misery and shedding of blood did indeed result from it, but not because of the faith of the Swiss Brethren, but because of the intolerant attitude of the government. It was actually the Protestant estates who insisted on it under the influence of the clergy. The Protestant cantons were very serious in their threat of making Anabaptism a capital crime. The bloody drama begun with Felix Manz in Zürich was continued in other Swiss cities. The <em>[[Martyrs' Mirror]]</em> names forty martyrs in Bern alone in 1529-1571. |

In the course of time there were frequent negotiations between the various cantons concerning the Anabaptists. On 4 July 1585, a conference between the city council of Bern and Zürich was held in Aarau, at which it was decided that those who clung to their faith after friendly instruction should be arrested and led out of the country. A resolution of 15 June 1660 repeated this order of expulsion. But love of country brought many an exile back to the homeland. | In the course of time there were frequent negotiations between the various cantons concerning the Anabaptists. On 4 July 1585, a conference between the city council of Bern and Zürich was held in Aarau, at which it was decided that those who clung to their faith after friendly instruction should be arrested and led out of the country. A resolution of 15 June 1660 repeated this order of expulsion. But love of country brought many an exile back to the homeland. | ||

| Line 92: | Line 92: | ||

Gratz, D. L. <em>Bernese Anabaptists and Their American Descendants.</em> Scottdale: 1953. | Gratz, D. L. <em>Bernese Anabaptists and Their American Descendants.</em> Scottdale: 1953. | ||

| − | Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. | + | Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. ''Mennonitisches Lexikon'', 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. IV, 128-132. |

Mennonite World Conference. "2000 Europe Mennonite & Brethren in Christ Churches." Web. 27 February 2011. [http://www.mwc-cmm.org/Directory/2000europe.html http://www.mwc-cmm.org/Directory/2000europe.html]. | Mennonite World Conference. "2000 Europe Mennonite & Brethren in Christ Churches." Web. 27 February 2011. [http://www.mwc-cmm.org/Directory/2000europe.html http://www.mwc-cmm.org/Directory/2000europe.html]. | ||

Revision as of 07:00, 16 January 2017

1959 Article

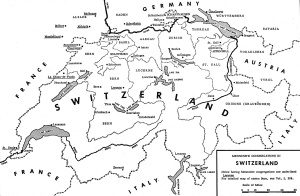

Switzerland, a mountainous country in the center of Europe, area 15,940 square miles (41,285 sq. km), population 7,288,010 in 2000, with eternally snow-covered Alpine ranges in the southern part, and the blue Jura Mountains in the northwest which extend from Geneva to Basel. Between the Alps and the Jura is the great Swiss plateau, which extends about 240 miles from Geneva to Lake Constance, a rolling terrain broken by smaller plains. Switzerland is a confederation of 22 cantons based on the principles of freedom of the old confederacy. Since the adoption of the new federal constitution in 1848 and its extension in 1874 the nation has become a strongly knit confederacy.

This mountainous land, whose inhabitants loved liberty and were for the most part earnestly religious, is the land of the birth of the Anabaptist movement and the homeland of innumerable refugee and emigrant Anabaptists or Mennonites. In the history of Anabaptism the early decades of the 16th century were of decisive significance. Of all the Anabaptist brotherhoods in Europe at the time of the Reformation, it is generally agreed that the group at Zürich was the first to constitute itself as a brotherhood alongside the prevailing church. The leaders were Conrad Grebel, Felix Manz, and George Blaurock. These men were the friends of Zwingli in the beginning of the Reformation. But as soon as he sponsored the establishment of a state church, and placed the religious leadership in the hands of the temporal government, they broke with him.

The strict Biblicism of the Zürich Brethren was also soon apparent in their adoption of the baptism of believers and the rejection of infant baptism. In a solemn hour on 21 January 1525, they openly confessed and confirmed their experience of salvation in baptism, although a few days before (January 18) the baptism of infants had been made obligatory by the city council. This was actually the founding of the first Anabaptist congregation. With fiery zeal they promoted the truth they recognized; recognition led to confession, with the result that the movement expanded to such an extent that in a short time there were thriving congregations not only in such Swiss towns as Zürich, St. Gall, Bern, and Basel, but far beyond the Swiss borders, in the Tyrol and South Germany, and adjoining German-speaking lands.

But the consequence was not only a great revival, but also the great tragedy in the history of the Anabaptist movement in the cruel persecution throughout Europe, which lasted more than two centuries in Switzerland. Zürich was first to adopt a policy of violent suppression under the influence of Zwingli. A large number of mandates were issued in the Swiss cities named above for the extermination of the movement. But when no other measures sufficed to crush the movement, the death penalty was adopted. The first death sentence of the new Protestant state church—which had only a short time before been in a severe battle for freedom of religion and conscience—was carried out on Felix Manz in Zürich on 5 January 1527. From then on, we find the Swiss confederacy in a constant struggle with the Anabaptist movement.

The Anabaptist problem was discussed as a federal issue in 1527. On Tuesday 2 August "the mayor, council and great council of the city of Zürich" sent an invitation to Bern, Basel, Schaffhausen, Chur, Appenzell, and St. Gall to meet in conference in Zürich on account of the Anabaptists, who were steadily increasing in spite of mild and also severe punishment. It was their opinion "that such sect and sinning should not be tolerated within or without our confederacy, since their intent is to destroy not only the true, right, inward faith of Christian hearts, but also external and human order and laws of Christian and orderly government, contrary to brotherly love and good morals." In order to preserve the common Christian peace and to serve the fatherland, the Zürich council proposed that the Protestant estates send a delegation to Zürich on 12-14 August to discuss the matter of punishing seditious Anabaptists.

An agreement (Concordat) was reached by the assembled cantons and a strict mandate issued against the Anabaptists. The document contains first a thorough justification of the mandate. Besides the "eternal and saving Word of God" the "sect and separation" of the Anabaptists had made itself felt, which, to be sure, seeks to defend its principles from the Bible. But it was clear that Anabaptism could not exist according to the Word of God, but must be rejected, and infant baptism be recognized, which had heretofore been practiced generally in Christendom and which is in accord with the Word of God.

Nevertheless the Swiss Brethren continued to increase in Switzerland. At the sessions of the federal parliament in Baden in January 1530, the Anabaptist question was again under discussion. The Protestant towns, Zürich, Bern, Basel, St. Gall, and Constance, united to adopt a common policy against the Anabaptists, because the "confused, miserable sect of the Anabaptists with their rabble and their doctrine are becoming everywhere more numerous and more dangerous, whereby in all true Christian faith great defection and division, much misery, shedding of blood and unrest results."

Much misery and shedding of blood did indeed result from it, but not because of the faith of the Swiss Brethren, but because of the intolerant attitude of the government. It was actually the Protestant estates who insisted on it under the influence of the clergy. The Protestant cantons were very serious in their threat of making Anabaptism a capital crime. The bloody drama begun with Felix Manz in Zürich was continued in other Swiss cities. The Martyrs' Mirror names forty martyrs in Bern alone in 1529-1571.

In the course of time there were frequent negotiations between the various cantons concerning the Anabaptists. On 4 July 1585, a conference between the city council of Bern and Zürich was held in Aarau, at which it was decided that those who clung to their faith after friendly instruction should be arrested and led out of the country. A resolution of 15 June 1660 repeated this order of expulsion. But love of country brought many an exile back to the homeland.

This policy of a "Christian government" toward its subjects in the hope of preserving unity of the church, practiced throughout the 16th-18th centuries, did not succeed in wiping out Anabaptism.

There is a vast amount of source material on the faith and life of the Swiss Brethren in the Reformation period. The basic principles are best found in the records of the Zofingen Disputation, 1-9 July 1532, and the debate (Täufergespräch) in Bern, 11-17 March 1538. Their doctrines agree exactly with the seven articles of the Schleitheim Confession of 1527. The center of the entire movement lay in the attempt to build their congregational life on the original sources of the Christian church. Their inner and outer life they sought to conform to the teaching of Christ, especially the Sermon on the Mount, and the apostolic teaching of salvation. They defended complete freedom of faith and conscience, the requirement of discipleship, rejection of the oath, and nonresistance, since the Christian should never take revenge, but always practice the love of one's enemy. To realize this New Testament, apostolic church, the first Anabaptists suffered severely. In this bitter contest they were, to be sure, defeated; it remained their only lot to endure injustice.

The causes of the Mennonite emigration from Switzerland were (1) persecution; (2) the military question or nonresistance; (3) an unfavorable economic situation and the restriction of opportunity for development. The large number of emigrations from Switzerland were in general not voluntary withdrawals, but rather expulsions from the country. To expel foreigners on account of religious propaganda in conflict with the state church might be understood; but to banish native citizens, quiet, obedient subjects on account of religious matters is today considered an impossibly severe punishment. Many Mennonites had to emigrate from the cantons of Bern and Zürich involuntarily, especially in the second period of the Zürich Anabaptist movement, the beginning of the 17th century. This wave of emigration removed the last of the Mennonites from the canton of Zürich by about 1700.

The first place of refuge where toleration for extra-church religious movements was found was Moravia. In the south of this margraviate, in the region of Nikolsburg, many Swiss Anabaptists settled. Balthasar Hubmaier was one of the first arrivals from Switzerland (1526). Here the Anabaptists were permitted to organize according to their principles, at least for a time. The Swiss Brethren formed an independent branch of the Moravian Anabaptists. At Jamnitz and other localities congregations of considerable size gathered. Emigrants from St. Gall and Appenzell joined these congregations.

From Moravia a number of Anabaptist emissaries undertook their dangerous missionary journeys to Switzerland, "to gather the lambs of the Lord." Three of these missionaries were captured in Zurzach (Aargau) in 1582 and executed in the town of Baden. Bern tried to stop the immigration to Moravia, fearing the loss of a large number of its subjects. It seems, however, that this missionary work was successful. The chronicles of the Hutterian Brethren report, "In this year, 1585, so many people came from Switzerland that they could not all be received; but a good part of them were received." And further, "In this 86th year several hundred Swiss came here to the brotherhood . . . who desired to adjust themselves in the faith."

A second major refuge was the Palatinate, especially in the 17th and 18th centuries. The large number of Mennonite family names of Swiss origin now in the Palatinate points to an extensive spread of Anabaptism through the immigration of Swiss Brethren. About 700 persons moved from the canton of Bern to the Palatinate in 1671 and arrived there in the most impoverished condition. The very first arrivals came as early as 1655.

Another place of refuge was the Netherlands (see Swiss Mennonites in the Netherlands). The Dutch Mennonites had most generously sympathized with their oppressed brethren. This matter was discussed at the general synod of the Mennonites in Amsterdam on 5 November 1670. The forcible deportation of the Mennonites to the East Indies or to America was thwarted by Dutch intervention. Some Swiss Brethren settled in Holland.

Numerous traces of Swiss emigration are found in Alsace-Lorraine and France. The fact that there are no Mennonites in the interior of France indicates immigration. The almost exclusively Bernese names substantiate their Bernese origin. In 1671-1711 there was a large settlement of Bernese Mennonites in Upper Alsace, in the Vosges and the French Jura (Doubs). In the Montbeliard area Count Leopold Eberhard put Mennonites in charge of his estates. These Mennonites thrived.

The later goal of emigrating Swiss Mennonites has been chiefly the United States. There were some Swiss Mennonites among the first Palatine Mennonite immigrants to Pennsylvania in the early 18th century. The immigration of Bernese Mennonites to America was very heavy in the first half of the 19th century. The Mennonites of Pennsylvania are of Swiss origin, nearly all from the canton of Bern, but some from Zürich. Emigration from the Emmental and the Jura was also very strong in 1830-1880. These Mennonites settled chiefly in Ohio, Indiana, and Ontario. A glance over the entire emigrant complex of Swiss Mennonites shows that many Mennonites in other lands are related by spiritual as well as blood ties to those of Switzerland.

Concerning the economic conditions of the Swiss Mennonites in the 16th-17th centuries there is little information. Living conditions even after the passing of persecution were extremely simple. These people were very modest in their demands and cultivated a quiet family life, regarding work as a God-given task. In spite of innumerable difficulties the Mennonites have pioneered in new methods of agriculture, which was their principal occupation. In the agricultural history of Switzerland and other adoptive lands the Swiss Mennonites occupy an outstanding place, which has been recognized by objective specialists. An unusual understanding of cattle raising and dairying can be found among the Swiss Mennonites.

Although large blocks of Swiss Mennonites have taken root and contributed to the growth of Mennonitism elsewhere, there has remained in Switzerland a remnant of Mennonite families, who call themselves the "Altevangelische taufgesinnte Gemeinde." The congregations are distributed as follows: Basel-Schänzli, with a meetinghouse since 1903; west of it close to the French border, Grand Lucelle, to which belong the Mennonites living on the lonely scattered farms as far as Delsberg. In the extreme north of the Bernese Jura lies Kleintal, with its center in the Moron chapel, built in 1893, and a meetinghouse in Perceux since 1921 above the cave in the mountain known as the Geisskirchlein, where tradition says the Mennonites used to hold their services during persecution. One of the largest congregations is Sonnenberg, southwest of Perceux, with its chapel Jeangisboden, built in 1900, and two other meetinghouses at Fürstenberg and Les Mottes. To the south, opposite the Chasseral chain, is the smallest congregation, Mont Cortébert of Cortébert-Matte. On the high plateau of the Jura is the Chaux d'Abel congregation, with a school erected in 1863, the gift of David Ummel to the congregation (burned down and rebuilt in 1917). The large chapel built in 1905 belongs to the young people's association, of which several Mennonites are members. Some of the Mennonites on Mt. Chaux d'Abel or Sonvilierberg meet in a hall in the home of the Jungen family. The canton of Neuchatel has only the Chaux de Fonds congregation. Its chapel was built in 1894 outside the town of Les Bulles. The former Locle-Bressels congregation is merged with Chaux de Fonds.

The most widely ramified and one of the largest congregations in Switzerland is the Emmental congregation with its seat at Langnau, where its organ, Der Zionspilger, is published. In Kehr near Langnau stands the first Mennonite chapel built in Switzerland. It was erected in 1888, and was followed by one at Bomatt a.d. Emme and one at Aebnit near Bowil in 1899. Subsidiaries of the Emmental congregation are found at Emmenholz near Solothurn and Pays de Gex near Geneva, which was founded early in the present century by Abraham Geiser.

All of these congregations are united into a conference, whose total membership varies from 1800 to 2,000 souls. The Basel congregation with a chapel on Holeestrasse belongs to the Alsatian conference. (See articles on all the Swiss cantons for detailed accounts, e.g. Bern).

From 1946 to 1952 the Mennonite Central Committee maintained its European headquarters at Basel, and since then has continued to have an office there, including the Agape Verlag established in 1954. In 1951 the European Mennonite Bible School was established in Basel, and moved in 1957 to Bienenberg near Liestal, some 10 miles inland. Basel has become the center of international Mennonite exchange and fellowship for Swiss, French, and South German Mennonites. In 1952 the Fifth Mennonite World Conference was held at St. Chrischona, near Basel.

2010 Update

Between 2000 and 2009 the following Anabaptist group was active in Switzerland:

| Denominations | Congregations in 2000 |

Membership in 2000 |

Congregations in 2003 |

Membership in 2003 |

Congregations in 2006 |

Membership in 2006 |

Congregations in 2012 |

Membership in 2012 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Konferenz der Mennoniten der Schweiz (Alttäufer), Conférence Mennonite Suisse (Anabaptiste) | 13 | 2,500 | 14 | 2,500 | 14 | 2,500 | 14 | 2,500 |

Bibliography

Burrage, H. S. A History of the Anabaptists in Switzerland. Philadelphia: 1882.

Correll, E. H. Das Schweizerische Täufer-mennonitentum. Tübingen: 1925.

Egli, E. Aktensammlung zur Gesch. der Züricher Reformation. Zürich: 1879.

Friedmann, R. Mennonite Piety Through the Centuries. Goshen: 1949.

Geiser, Samuel. Die Taufgesinnten-Gemeinden. Karlsruhe: 1931.

Gratz, D. L. Bernese Anabaptists and Their American Descendants. Scottdale: 1953.

Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. Mennonitisches Lexikon, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. IV, 128-132.

Mennonite World Conference. "2000 Europe Mennonite & Brethren in Christ Churches." Web. 27 February 2011. http://www.mwc-cmm.org/Directory/2000europe.html.

Mennonite World Conference. "2003 Europe Mennonite & Brethren in Christ Churches." Web. 27 February 2011. http://www.mwc-cmm.org/Directory/2003europe.html.

Mennonite World Conference. "Europe." Web. 27 February 2011. http://www.mwc-cmm.org/Directory/2006europe.pdf.

Mennonite World Conference. World Directory = Directorio mundial = Répertoire mondial 2012: Mennonite, Brethren in Christ and Related Churches = Iglesias Menonitas, de los Hermanos en Cristo y afines = Églises Mennonites, Frères en Christ et Apparentées. Kitchener, ON: Mennonite World Conference, 2012: 16.

Müller, Ernst. Geschichte der Bernischen Täufer. Frauenfeld: Huber, 1895. Reprinted Nieuwkoop : B. de Graaf, 1972.

Muralt, Leonhard von and Walter Schmid. Quellen zur Geschichte der Täufer in der Schweiz. Erster Band Zürich. Zürich: S. Hirzel, 1952.

Nitsche, R. Geschichte der Wiedertäufer in der Schweiz. Einsiedeln: 1885.

Peachey, Paul. Die soziale Herkunft der Schweizer Täufer. Karlsruhe: 1954.

Thormann, G. Probierstein oder . . . Prüfung des Täuffertums. Bern: 1693.

von Muralt, L. Glaube und Leben der schweizerischen Täufer in der Reformationszeit. Zürich: 1938.

Wolkan, Rudolf. Geschicht-Buch der Hutterischen Brüder. Macleod, AB, and Vienna, 1923.

| Author(s) | Samuel Geiser |

|---|---|

| Date Published | February 2011 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Geiser, Samuel. "Switzerland." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. February 2011. Web. 16 Apr 2024. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Switzerland&oldid=146282.

APA style

Geiser, Samuel. (February 2011). Switzerland. Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 16 April 2024, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Switzerland&oldid=146282.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 4, pp. 673-677. All rights reserved.

©1996-2024 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.