Difference between revisions of "Ulm (Baden-Württemberg, Germany)"

| [checked revision] | [checked revision] |

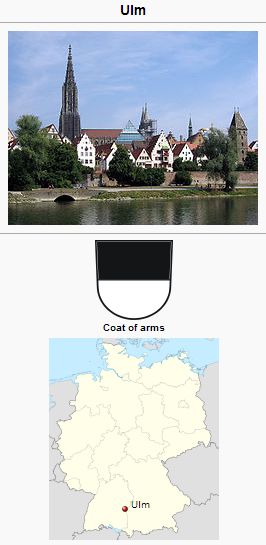

m (Added image.) |

SusanHuebert (talk | contribs) m |

||

| (One intermediate revision by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

Ulm, a city (1959 population, 69,941; 2011 population, 123,672; coordinates: 48.4, 9.983333 [48° 24′ 0″ N, 9° 59′ 0″ E]) in [[Baden-Württemberg (Germany)|Baden-Württemberg]], Germany, located on the Danube, until 1803 a free city of the empire. Here the [[Reformation, Protestant|Reformation]] was introduced about 1524-26 by [[Sam, Konrad (1483-1535)|Konrad Sam]], and continued by [[Bucer, Martin (1491-1551)|Bucer]], [[Oecolampadius, Johannes (1482-1531)|Oecolampadius]], [[Blaurer, Ambrosius (1492-1564)|Blaurer]], and Rabus. During the first 20 years it was Zwinglian in character, but after a bitter struggle Lutheranism took the upper hand. In consequence of this unpleasant strife, serious, peaceful citizens turned away from the church of [[Luther, Martin (1483-1546)|Luther]] and [[Zwingli, Ulrich (1484-1531)|Zwingli]] and joined the [[Anabaptism|Anabaptists]]. It may have been Simon Stumpf who transplanted Anabaptist ideas into Ulm, on which [[Hut, Hans (d. 1527)|Hans Hut]] built in 1527 and [[Reublin, Wilhelm (1480/84-after 1559)|Wilhelm Reublin]] in 1528. It is reported that Reublin was for a time the leader (<em>Vorsteher</em>) of the congregation. According to the report of the magistrate on 16 September 1527, [[Denck, Hans (ca. 1500-1527)|Hans Denck]], [[Haetzer, Ludwig (1500-1529)|Ludwig Haetzer]], and B. Beckenknecht ([[Beck, Hans (16th century)|Hans Beck]]) lived here for a while too. They probably came from [[Augsburg (Freistaat Bayern, Germany)|Augsburg]], where they had attended the [[Martyrs' Synod|Martyrs' Synod]] on 20 August 1527. But the council saw to it that they soon left the city. Among the prominent converts were the councillors and master goldsmiths Hans Müller and Daniel Hochweher. | Ulm, a city (1959 population, 69,941; 2011 population, 123,672; coordinates: 48.4, 9.983333 [48° 24′ 0″ N, 9° 59′ 0″ E]) in [[Baden-Württemberg (Germany)|Baden-Württemberg]], Germany, located on the Danube, until 1803 a free city of the empire. Here the [[Reformation, Protestant|Reformation]] was introduced about 1524-26 by [[Sam, Konrad (1483-1535)|Konrad Sam]], and continued by [[Bucer, Martin (1491-1551)|Bucer]], [[Oecolampadius, Johannes (1482-1531)|Oecolampadius]], [[Blaurer, Ambrosius (1492-1564)|Blaurer]], and Rabus. During the first 20 years it was Zwinglian in character, but after a bitter struggle Lutheranism took the upper hand. In consequence of this unpleasant strife, serious, peaceful citizens turned away from the church of [[Luther, Martin (1483-1546)|Luther]] and [[Zwingli, Ulrich (1484-1531)|Zwingli]] and joined the [[Anabaptism|Anabaptists]]. It may have been Simon Stumpf who transplanted Anabaptist ideas into Ulm, on which [[Hut, Hans (d. 1527)|Hans Hut]] built in 1527 and [[Reublin, Wilhelm (1480/84-after 1559)|Wilhelm Reublin]] in 1528. It is reported that Reublin was for a time the leader (<em>Vorsteher</em>) of the congregation. According to the report of the magistrate on 16 September 1527, [[Denck, Hans (ca. 1500-1527)|Hans Denck]], [[Haetzer, Ludwig (1500-1529)|Ludwig Haetzer]], and B. Beckenknecht ([[Beck, Hans (16th century)|Hans Beck]]) lived here for a while too. They probably came from [[Augsburg (Freistaat Bayern, Germany)|Augsburg]], where they had attended the [[Martyrs' Synod|Martyrs' Synod]] on 20 August 1527. But the council saw to it that they soon left the city. Among the prominent converts were the councillors and master goldsmiths Hans Müller and Daniel Hochweher. | ||

| − | On 14 February 1528, the severe imperial mandate (see [[Mandates|Mandates]]) was read to the populace as a deterrent to the movement. From this time on many [[Anabaptism|Anabaptists]] were called to give an account of themselves before the privy council; among them were Daniel Hochweher and his wife and sister, and also | + | On 14 February 1528, the severe imperial mandate (see [[Mandates|Mandates]]) was read to the populace as a deterrent to the movement. From this time on many [[Anabaptism|Anabaptists]] were called to give an account of themselves before the privy council; among them were Daniel Hochweher and his wife and sister, and also Claus Sporer on 13 July. Sporer declared that he was not an Anabaptist (i.e., rebaptizer), for "his first baptism had not been anything; it had given nothing and taken nothing; therefore it was without value." He made a sharp distinction between those who held their wives and all things in common and rejected authority (the [[Münster Anabaptists|Münsterites]]) and the group in Ulm. |

Expulsions from the city now were ordered, especially because Diepold von Stein, the captain of the [[Swabian League|Swabian League]], earnestly admonished the Ulm commander, Philipp von Wenkheim, to pursue the Anabaptists with more rigor. Von Wenkheim replied that he had orders to act rigorously only in case of sedition. In Ulm they were trying to meet the situation first by indoctrination; if this was fruitless, they expelled the obstinate from the city; if they returned, they were put into the tower. | Expulsions from the city now were ordered, especially because Diepold von Stein, the captain of the [[Swabian League|Swabian League]], earnestly admonished the Ulm commander, Philipp von Wenkheim, to pursue the Anabaptists with more rigor. Von Wenkheim replied that he had orders to act rigorously only in case of sedition. In Ulm they were trying to meet the situation first by indoctrination; if this was fruitless, they expelled the obstinate from the city; if they returned, they were put into the tower. | ||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

A courageous, steadfast Anabaptist was Abraham Schneider, also called Brendlin. He defended himself with great ability. He said that if the children had a hidden faith, as was claimed, then they should also have a hidden baptism; an [[Oath|oath]] was permissible to a Christian in case it was not contrary to God, contrary to the love of one's neighbor, or contrary to the conscience of the person rendering the oath. It is thus evident that the Ulm Anabaptists were Swiss Brethren. Because they would not accept instruction they had to leave the city territory. Other leading Anabaptists were the physician Nicolas Lauer, [[Wernlin, Jörg (d. ca. 1559)|Jörg Wernlin]], and Hans Glaser. | A courageous, steadfast Anabaptist was Abraham Schneider, also called Brendlin. He defended himself with great ability. He said that if the children had a hidden faith, as was claimed, then they should also have a hidden baptism; an [[Oath|oath]] was permissible to a Christian in case it was not contrary to God, contrary to the love of one's neighbor, or contrary to the conscience of the person rendering the oath. It is thus evident that the Ulm Anabaptists were Swiss Brethren. Because they would not accept instruction they had to leave the city territory. Other leading Anabaptists were the physician Nicolas Lauer, [[Wernlin, Jörg (d. ca. 1559)|Jörg Wernlin]], and Hans Glaser. | ||

| − | Even if the Ulm congregation never attained the importance of the Augsburg congregation, Ulm was nevertheless an important point on the route of Anabaptist leaders who led to [[Moravia (Czech Republic)|Moravia]] the converts they had won in Switzerland or along the Rhine. The Anabaptists lodged in the inn "To the Sun" near the bridge over the Danube until the boatmen of Ulm took them further on the Danube. The council decided that it would have to comply with the order of Duke Ernest not to aid the Anabaptists in this way any longer. Thereupon in 1587 the two Anabaptist leaders, Jörg Gutter and Christoph Hirzel, the latter a native of [[Zürich (Switzerland)|Zürich]], were arrested in Ulm. By threats of the rack, the authorities vainly tried to force admissions about their brethren. But the severer measures were not applied; instead, the men were expelled from Ulm and its territory. Although the council of Ulm was relatively lenient in its treatment of the Anabaptists, never for instance confiscating their property, nevertheless under the decisive action of the church superintendent Ludwig Rabus (1556-92) the Anabaptist movement in Ulm died out. | + | Even if the Ulm congregation never attained the importance of the Augsburg congregation, Ulm was nevertheless an important point on the route of Anabaptist leaders who led to [[Moravia (Czech Republic)|Moravia]] the converts they had won in Switzerland or along the Rhine. The Anabaptists lodged in the inn "To the Sun" near the bridge over the Danube until the boatmen of Ulm took them further on the Danube. The council decided that it would have to comply with the order of Duke Ernest not to aid the Anabaptists in this way any longer. Thereupon in 1587 the two Anabaptist leaders, Jörg Gutter and Christoph Hirzel, the latter a native of [[Zürich (Switzerland)|Zürich]], were arrested in Ulm. By threats of the rack, the authorities vainly tried to force admissions about their brethren. But the severer measures were not applied; instead, the men were expelled from Ulm and its territory. Although the council of Ulm was relatively lenient in its treatment of the Anabaptists, never for instance confiscating their property, nevertheless under the decisive action of the church superintendent [[Rabe, Ludwig (1514-1592)|Ludwig Rabus]] (1556-92) the Anabaptist movement in Ulm died out. |

| − | Fritz Friedrich thinks it must be assumed that many of those with Anabaptist inclinations united with the Schwenckfelders in order to avoid persecution, for the latter group was tolerated for a long time in Ulm; and also that | + | Fritz Friedrich thinks it must be assumed that many of those with Anabaptist inclinations united with the Schwenckfelders in order to avoid persecution, for the latter group was tolerated for a long time in Ulm; and also that [[Streicher, Helena (d. 1549)|Helena Streicher]], the widow of a merchant, and her daughter Agathe, who later became Schwenckfelders, must originally have been Anabaptists. The latter was a widely known physician; the bishops of [[Mainz (Rheinland-Pfalz, Germany)|Mainz]] and even Maximilian demanded her services. Friedrich also thinks that in all probability [[Schwenckfeld, Caspar von (1489-1561)|Schwenckfeld]] spent the last period of his life in the Streicher home on the square in Ulm on Agathe's invitation; he died there on 10 December 1561, and was secretly buried in the basement. After 1589 nothing more is heard of Anabaptists in Ulm. |

= Bibliography = | = Bibliography = | ||

Bossert, Gustav. <em class="gameo_bibliography">Quellen zur Geschichte der Täufer I. Band, Herzogtum Württemberg</em>. Leipzig: M. Heinsius, 1930. | Bossert, Gustav. <em class="gameo_bibliography">Quellen zur Geschichte der Täufer I. Band, Herzogtum Württemberg</em>. Leipzig: M. Heinsius, 1930. | ||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

Egelhaar, Gottlob. "Geschichte der Reichsstadt Ulm." <em class="gameo_bibliography">Beschreibung des Oberamts Ulm II</em>. Ulm, 1897: 32 ff. | Egelhaar, Gottlob. "Geschichte der Reichsstadt Ulm." <em class="gameo_bibliography">Beschreibung des Oberamts Ulm II</em>. Ulm, 1897: 32 ff. | ||

| − | Friedrich, Fritz. "Ulmische | + | Friedrich, Fritz. "Ulmische Kirchengeschichte vom Interim bis zum 30-jahrigen Krieg 1548-1612." <em class="gameo_bibliography">Blätter für württembergische Kirchengeschichte</em>, n.s. I (1933): No. 3-4. |

| − | Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. <em class="gameo_bibliography">Mennonitisches Lexikon</em>, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. IV. | + | Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. <em class="gameo_bibliography">Mennonitisches Lexikon</em>, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. IV, 378-379. |

Keidel, Fr. "Ulmische Religionsakten 1531-1552." <em class="gameo_bibliography">Württembergische Vierteljahreshefte</em> (1896): 255. | Keidel, Fr. "Ulmische Religionsakten 1531-1552." <em class="gameo_bibliography">Württembergische Vierteljahreshefte</em> (1896): 255. | ||

Revision as of 17:01, 8 July 2015

Ulm, a city (1959 population, 69,941; 2011 population, 123,672; coordinates: 48.4, 9.983333 [48° 24′ 0″ N, 9° 59′ 0″ E]) in Baden-Württemberg, Germany, located on the Danube, until 1803 a free city of the empire. Here the Reformation was introduced about 1524-26 by Konrad Sam, and continued by Bucer, Oecolampadius, Blaurer, and Rabus. During the first 20 years it was Zwinglian in character, but after a bitter struggle Lutheranism took the upper hand. In consequence of this unpleasant strife, serious, peaceful citizens turned away from the church of Luther and Zwingli and joined the Anabaptists. It may have been Simon Stumpf who transplanted Anabaptist ideas into Ulm, on which Hans Hut built in 1527 and Wilhelm Reublin in 1528. It is reported that Reublin was for a time the leader (Vorsteher) of the congregation. According to the report of the magistrate on 16 September 1527, Hans Denck, Ludwig Haetzer, and B. Beckenknecht (Hans Beck) lived here for a while too. They probably came from Augsburg, where they had attended the Martyrs' Synod on 20 August 1527. But the council saw to it that they soon left the city. Among the prominent converts were the councillors and master goldsmiths Hans Müller and Daniel Hochweher.

On 14 February 1528, the severe imperial mandate (see Mandates) was read to the populace as a deterrent to the movement. From this time on many Anabaptists were called to give an account of themselves before the privy council; among them were Daniel Hochweher and his wife and sister, and also Claus Sporer on 13 July. Sporer declared that he was not an Anabaptist (i.e., rebaptizer), for "his first baptism had not been anything; it had given nothing and taken nothing; therefore it was without value." He made a sharp distinction between those who held their wives and all things in common and rejected authority (the Münsterites) and the group in Ulm.

Expulsions from the city now were ordered, especially because Diepold von Stein, the captain of the Swabian League, earnestly admonished the Ulm commander, Philipp von Wenkheim, to pursue the Anabaptists with more rigor. Von Wenkheim replied that he had orders to act rigorously only in case of sedition. In Ulm they were trying to meet the situation first by indoctrination; if this was fruitless, they expelled the obstinate from the city; if they returned, they were put into the tower.

In the villages round about Ulm there were also many Anabaptists. Again and again they were summoned to answer to the religious authorities. In Bohningen they had free entry to the home of the pastor, Martin Karter, since "they liked to hear his sermons." The parson was said to have stated that if he were the ruler of the land he would not expel any Anabaptists.

A courageous, steadfast Anabaptist was Abraham Schneider, also called Brendlin. He defended himself with great ability. He said that if the children had a hidden faith, as was claimed, then they should also have a hidden baptism; an oath was permissible to a Christian in case it was not contrary to God, contrary to the love of one's neighbor, or contrary to the conscience of the person rendering the oath. It is thus evident that the Ulm Anabaptists were Swiss Brethren. Because they would not accept instruction they had to leave the city territory. Other leading Anabaptists were the physician Nicolas Lauer, Jörg Wernlin, and Hans Glaser.

Even if the Ulm congregation never attained the importance of the Augsburg congregation, Ulm was nevertheless an important point on the route of Anabaptist leaders who led to Moravia the converts they had won in Switzerland or along the Rhine. The Anabaptists lodged in the inn "To the Sun" near the bridge over the Danube until the boatmen of Ulm took them further on the Danube. The council decided that it would have to comply with the order of Duke Ernest not to aid the Anabaptists in this way any longer. Thereupon in 1587 the two Anabaptist leaders, Jörg Gutter and Christoph Hirzel, the latter a native of Zürich, were arrested in Ulm. By threats of the rack, the authorities vainly tried to force admissions about their brethren. But the severer measures were not applied; instead, the men were expelled from Ulm and its territory. Although the council of Ulm was relatively lenient in its treatment of the Anabaptists, never for instance confiscating their property, nevertheless under the decisive action of the church superintendent Ludwig Rabus (1556-92) the Anabaptist movement in Ulm died out.

Fritz Friedrich thinks it must be assumed that many of those with Anabaptist inclinations united with the Schwenckfelders in order to avoid persecution, for the latter group was tolerated for a long time in Ulm; and also that Helena Streicher, the widow of a merchant, and her daughter Agathe, who later became Schwenckfelders, must originally have been Anabaptists. The latter was a widely known physician; the bishops of Mainz and even Maximilian demanded her services. Friedrich also thinks that in all probability Schwenckfeld spent the last period of his life in the Streicher home on the square in Ulm on Agathe's invitation; he died there on 10 December 1561, and was secretly buried in the basement. After 1589 nothing more is heard of Anabaptists in Ulm.

Bibliography

Bossert, Gustav. Quellen zur Geschichte der Täufer I. Band, Herzogtum Württemberg. Leipzig: M. Heinsius, 1930.

Dietrich, H. D. Konrad Dietrich und sein Briefwechsel. Ulm, 1938: 42.

Egelhaar, Gottlob. "Geschichte der Reichsstadt Ulm." Beschreibung des Oberamts Ulm II. Ulm, 1897: 32 ff.

Friedrich, Fritz. "Ulmische Kirchengeschichte vom Interim bis zum 30-jahrigen Krieg 1548-1612." Blätter für württembergische Kirchengeschichte, n.s. I (1933): No. 3-4.

Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. Mennonitisches Lexikon, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. IV, 378-379.

Keidel, Fr. "Ulmische Religionsakten 1531-1552." Württembergische Vierteljahreshefte (1896): 255.

Keim, Karl Theodor. Die Reformation der Reichsstadt Ulm. Ulm. 1851.

Thudichum, Fr. Die Deutsche Reformation II. Leipzig, 1909.

| Author(s) | Wilhelm Wiswedel |

|---|---|

| Date Published | 1959 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Wiswedel, Wilhelm. "Ulm (Baden-Württemberg, Germany)." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1959. Web. 18 Apr 2024. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Ulm_(Baden-W%C3%BCrttemberg,_Germany)&oldid=132087.

APA style

Wiswedel, Wilhelm. (1959). Ulm (Baden-Württemberg, Germany). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 18 April 2024, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Ulm_(Baden-W%C3%BCrttemberg,_Germany)&oldid=132087.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 4, p. 770. All rights reserved.

©1996-2024 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.