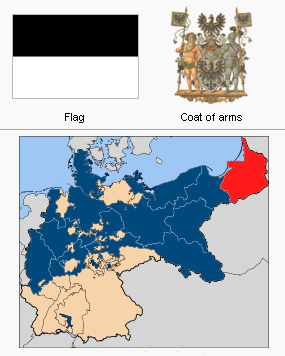

East Prussia

Source: Wikipedia Commons

The Anabaptists in the Early Years of the Reformation

East Prussia consists for the most part of the eastern part of the former land of the Teutonic Knights, as it existed for several centuries as the Duchy of Prussia (or Ducal Prussia), whereas West or Royal (Polish) Prussia was separated from the Teutonic Knight state in 1466 and assigned to the Polish crown. The last grand master of the Teutonic Order, Albrecht von Hohenzollern, secularized the remainder of the Teutonic Order lands in 1525 and made of them a hereditary duchy under the loose sovereignty of Poland. The duchy became known as East Prussia in 1773 when it became a province of the Kingdom of Prussia, while Royal Prussia became the province of West Prussia. The two were united in 1829 to form the Province of Prussia, but were again separated into separate provinces in 1878. After 1918 the kingdom of Prussia was abolished and East Prussia was separated from the rest of Germany, and after World War II, East Prussia was partitioned between Poland and the Soviet Union. Southern East Prussia was placed under Polish administration, while northern East Prussia was divided between the Soviet republics of Russia (the Kaliningrad Oblast) and Lithuania (the constituent counties of the Klaipėda Region).

Although Duke Albrecht's decision can be traced to the influence of Luther, in the first years of his reign he was not unfavorable to the separatist religious groups, being influenced by the mighty Baron Frederick of Heydeck. Because of an initial scarcity of Protestant pastors in the duchy, Heydeck traveled to Silesia, came in contact with Caspar Schwenckfeld here, and brought clergymen of his stripe to Prussia. The duke himself engaged in religious correspondence with Schwenckfeld in 1527-1528. It was the followers of Schwenckfeld in Prussia who were in the first decade of the Reformation called Anabaptists by the Lutheran clergy. Between Schwenckfeld and the Lutheran bishop Paulus Speratus a colloquium took place in the presence of the duke and Heydeck on 29 and 30 December 1531. In 1532, upon inquiry by the duke, Luther demanded the expulsion of all the Sacramentist (Reformed) and Anabaptist elements out of the duchy. In the early years of Albrecht's rule, some of the most important men, even some of his councilors, were Anabaptists or akin to them. In 1536 Christian Entfelder, a native of Carinthia, who was probably a preacher in the Moravian Anabaptist brotherhood 1526-1527, became a ducal councilor, and in the next ten years was very influential at the court in Königsberg. Of him Speratus wrote to Poliander in 1539: "Entfelder is exceedingly cunning; he writes nothing on the sacraments but as a Sacramentist and as an Anabaptist"; and to a friend in Wittenberg in 1542: "I nominate Entfelder, formerly the antistes in Moravia."

In July 1541 the Dutch Humanist William Gnapheus became a ducal councilor, though it was known of him that he was "not ill informed and learned in the Scripture," but otherwise "somewhat attached to the Anabaptist or other fanatical sects." He held occasional theological lectures in the recently established University of Königsberg. On 22 February, 1542, Gerhard Westerburg of Cologne, known as an Anabaptist in Frankfurt, became a ducal councilor. Polyphem, the court librarian, and Pyrsus, the Dutch physician, held views similar to those of the above and were closely associated with them. To what extent they openly espoused their views is an open question. But their influence on the court was so great that the Lutheran bishop did not venture to oppose them publicly.

It is easily understood that under such circumstances Mennonite refugees would seek asylum in Prussia, especially in view of the close trade connections between the two countries. To Polish Prussia they could not yet go, since the Polish king had in 1526 had a large number of Danzig citizens executed because they were too ardently Protestant, and also since the incoming ships were carefully examined for heretics.

In the Prussian duchy, however, the first Dutch settlers came in 1527, locating in its western tip, in the Oberland that had been devastated by the Reuter war (1519-1525). They were assigned to the desolate villages of Bardeyn, Thierbach, Schmauch, Liebenau, Plehmen, and Robitten, with an area of about 9,000 acres. The first settlers were not Anabaptists, but by 15 years later these lands were almost exclusively occupied by Mennonites. The land-complex on which these Mennonites settled became the nucleus of the entire Mennonite settlement in East Germany. Refugees continued to come from the Netherlands to Bardeyn and the neighboring villages, while others of the settlers left; there was a constant fluctuation.

The theological position of the Dutch in the duchy reflected the first decades of the Reformation in the Netherlands. Until the early 1530s the immigrants were almost all Sacramentists (forerunners of the Anabaptists and also of the Zwinglians), who differed radically from Luther in their interpretation of the communion. After the middle 1530s following the appearance of Melchior Hoffman in the Netherlands, the Protestants in the Prussian lowlands were more and more of the Anabaptist persuasion.

The violence of the Münster episode (1534-1535) and the attack by radical Anabaptists on the city hall in Amsterdam (1535) fanned the persecution mania of the Dutch and German authorities to the uttermost. But not only the revolutionary Anabaptists, but also the great mass of quiet Anabaptists who had nothing to do with violence, were persecuted with fire and sword. In this period therefore faraway Prussia, whose ruler was himself an imperial outlaw, in whose land the imperial laws against the Anabaptists were no longer valid, seemed a final place of refuge to the harassed souls.

In early 1535 a company of some 200 Moravian Anabaptist refugees came to Marienwerder by way of Thorn and Graudenz. A disputation with them revealed their "error," and they were banished. Nevertheless a part of them remained, protected by the mighty Baron of Heydeck.

After 1534 nearly every boat brought persecuted Anabaptists from the Netherlands to the shores of Prussia, especially to the Polish part. In the early summer of 1536 the estate Robitten near Bardeyn was given out to Johann Solius, an Anabaptist and a follower of Melchior Hoffman, but at the end of the year he left the estate and went to Danzig. There was a flow of Anabaptists into Danzig and to the rest of West Prussia, although it cannot be determined which were the revolutionary type and which were peaceful Anabaptists.

Peaceful Anabaptists in the Duchy

Soon after Menno Simons came upon the scene, the entire Anabaptist movement (including that part in Prussia) took quieter channels. The Dutch refugees now sought not only a temporary place of refuge in the Oberland, but were obviously settling there permanently. Therefore a second area of about 4,500 acres about six miles north of Prussian Holland was given them in 1539, giving their total settlement about 30 square miles. In 1538-1539 a number of families were negotiating in Königsberg concerning these lands. It is significant that Christian Entfelder conducted the negotiations for the government. The spokesman of the Dutch was Herman Sachs, who was known to have been an Anabaptist before he left the Netherlands. The village of Schönberg with 1,800 acres of land was to be occupied first by them; later Judendorf and Greulsberg were to follow. In religious matters they were to obey their local diocese. They were released from compulsory state labor. All mention of military service was omitted from this treaty in contrast to those made with the Sacramentist Dutch immigrants of 1527-1529. Very likely the Anabaptist settlers wished to have these passages eliminated, especially in order to distinguish them from the Münsterite group.

The Dutch settlers were punctual in meeting their financial obligations, but in church relationships they soon aroused the ill will of Bishop Speratus. A letter of complaint written by the local parson in 1542 made it clear that the Dutch did not give weight to either the sacrament of the altar or that of baptism, that they did not go to the Lutheran churches in general, and acted contrary to the Prussian church regulations. Until then they had had a preacher, the letter went on: on Sunday they met with his widow, who read to them from the Bible, though they were forbidden to have a preacher of their own and "to preach secretly." All these facts show that these people were quiet Anabaptists.

Suddenly these conditions came to an end; a church inspection was made by the duke with his bishops and councilors in early 1543. It was ascertained that the Dutch immigrants did not adhere to the Prussian church discipline in matters of communion and baptism. They were thereupon ordered to place persons with "pure doctrine" on their farms and leave by Pentecost. Most of them were loyal to their faith. A small minority promised to obey the Prussian church constitution in order to be able to remain. But Bishop Speratus kept a watchful eye on these, for the same heresy again became evident, so that the bishop had to threaten them with expulsion in 1550.

This first Anabaptist settlement in East Prussia was given a mortal blow by the order of expulsion of 1543, though some isolated new settlements were still made. In 1557 Tonnies Florissen owned the village of Schönberg as mayor. He was the only one paying taxes until 1561, although he had his property together with the other Mennonites in the Danzig Werder. Schönberg was temporarily held as a land reserve until the areas in the Tiegenhof district were opened to the Mennonites for settlement in 1562. Now the 30 square miles in the Oberland were no longer needed; they had already been given up in large part with their woods and hills, having been little suited to the Dutch mode of agriculture.

The Dutch colonists who settled on the city estates of Königsberg, especially in Rossgarten after the middle of the 1520s, fared exactly like those in the Oberland. Although they had a strong support in their fellow countrymen at court, the majority of the Dutch had to leave Königsberg for religious reasons. For in Königsberg-Rossgarten there was also a church inspection, which revealed the same deviations from Lutheran doctrine with respect to communion and baptism.

The Oberland Anabaptists we find again among the settlers who were placed on the flooded lands of the Danzig lowlands in 1547. The Anabaptists of Königsberg may also to a large extent have gone to Danzig or Elbing; this would explain the sudden increase in the number of Anabaptists in these cities in the next few years.

The Anabaptists who moved from the duchy to the Danzig Werder and to Polish Prussia in 1543 belonged for the most part to the group later called Mennonites; for there is no mention of any other wing after this time in Prussia. Menno Simons himself visited the Anabaptists here in 1549.

In spite of the various decrees of expulsion, the Mennonites were able to maintain themselves in Königsberg even after 1543. In 1579 they presented to the ruler a statement of their chief doctrines and a petition for permission to settle freely in the duchy. The reply was negative, because they "first of all regarded the sacrament of infant baptism quite offensively and mockingly." By May they were to leave the country. Church and school inspections continued to show that "all kinds of rabble and sects, especially the Anabaptists, had settled in the duchy." This is also shown by the continued issuing of decrees of expulsion. In 1669 they received some recognition; the Mennonites were permitted to come to the country on business, but not to settle permanently in either town or rural areas; when their business was finished they had to return to their home towns. Nevertheless some Mennonites acquired property at this time, although no congregation was formed.

The Mennonite Congregations of East Prussia as Daughter Colonies of West Prussia

Pietism and Rationalism broke wide gaps into the dogmatism of the Lutheran Church in the 17th and 18th centuries. The tolerance extended to the Reformed and Catholics for a century was now also applied to the Mennonites. When Frederick I of Prussia in 1710 tried with all the means at his disposal to settle Swiss Mennonite refugees—without success, to be sure—in the towns of East Prussia in Lithuania which had been depopulated by the plague, a new era began for Mennonite history in East Prussia.

The efforts of the West Prussian Mennonites at settlement in East Prussia in the 18th century concentrate on two points. The first Mennonite craftsmen and merchants to settle in Königsberg with the permission of the authorities came in 1716. One of their specialties was the distillation of a certain whiskey "in the Danzig manner." They brought trades to Königsberg which had existed there only in a primitive state or not at all. In 1722 a small but prosperous congregation was organized, with members from Danzig and Elbing, and a few of Dutch birth. In 1735 the young congregation numbered 22 families, and later under Frederick the Great 35 families. Though they were small in number in 1769, they built a church, and two almshouses with facilities for six families.

The second region in which West Prussian Mennonites settled after 1713 is the delta mouth of the Memel and its left tributary, the Gilge. Here they found a colonization site that suited their way of farming better than the woods and hills of Preussisch-Holland. Most of them came from the Graudenz and Culm lowlands along the Vistula, and formed a congregation of the Frisian branch. Some of the names of the colonists have been handed down from 1722, names at that time found almost exclusively in the Frisian congregations in West Prussia: Albrecht, Barthel, Becker, Eckert, Frantzen, Funck, Harms, Heinrichsen, Jansen, Kettler, Lorentz, Penner, Quapp, Quiring, Rhode, Schröder, Siebert, Sperling, Schmidt, and Weitgraf.

The colonizing contracts of this group show a tendency similar to that of their compatriots who had been shut out from the Oberland 200 years before. They were guaranteed freedom of religion and of trade, were permitted to elect their own mayor, divide the land among themselves without anyone else, and the division was to be "as binding as if they had been done in court." They accepted a piece of land, and paid a large price for it in order to arrange everything according to their own wishes. They wanted to build up their religious, political, and economic life according to their own ideas, at a time when almost everything was determined by an absolute ruler.

The Memel lowland with its excellent meadows gave the Mennonites almost the same living conditions as did West Prussia. Their knowledge of cattle raising and of butter and cheese manufacture assured them a decided advantage over the native peasants. In 1723 they were supplying the market in Königsberg nearly 400 tons of "Mennonite" cheese, which was known all over East Germany as Tilsit cheese. But in the next year they were expelled from the Memel lowlands; this attempt at colonization was ended. Frederick William would not tolerate in his country any who would not be soldiers. Only the Mennonite merchants in Königsberg who were indispensable because of their contributions to the taxes, were permitted to stay.

When Frederick the Great came to the throne in 1740 with his principle of toleration, he issued a declaration that guaranteed tolerance to the Mennonites as to all other subjects; the way was now opened to them to make new settlements along the Memel. The Lithuanian congregation then came into being, which had in 1772 a membership of over 200 souls, and in 1890 with its 743 souls within the government district of Gumbinnen reached its highest point. In 1891 it acquired the rights of incorporation. In its final period before its dissolution in 1945, it is worth noting that in the 1920s this congregation, called Memelniederung, engaged a theologically trained pastor, but in 1931 returned to the lay ministry. A peculiarity of this congregation was the use of the liturgy of the Lutheran Church. In 1940 the congregation still had a membership of 450 souls. Both this congregation and the smaller Königsberg congregation were completely wiped out by the Russian conquest in 1944-45. Numerous survivors however reached West Germany and were scattered throughout the country.

Bibliography

The Mennonite archives at Amsterdam contain a large number of documents concerning the East Prussian Mennonites, especially from the early 18th century.

Beheim-Schwarzbach, Max. Hohenzollernsche Colonisationen: Ein Beitrag zu der Geschichte des preussischen Staates und der Colonisation des östlichen Deutschlands. Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, 1874.

Brons, Anna. Ursprung, Entwickelung und Schicksale der altevangelischen Taufgesinnten oder Mennoniten. Amsterdam: Johannes Muller, 1912: 195-206.

Cosack, C. J. Paulus Speratus Leben und Lieder: Ein Beitrag zur Reformationsgeschichte, besonders zur preussischen, wie zur Hymnologie. Braunschweig: C.A. Schwetschke, 1861.

Hartknoch, B. M. Ch. Preussische Kirchenhistorie. Frankfurt and Leipzig, 1886.

Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. Mennonitisches Lexikon, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. III, 322-325.

Keyser, Erich. "Die Niederlande und das Weichselland." Deutsches Archiv für Landes- und Volksforschung VI (1942): 592-617.

Mannhardt, H. G. Die Danziger Mennonitengemeinde: ihre Entstehung und ihre Geschichte von 1569-1919.Danzig : Danziger Mennonitengemeinde, 1919. (English translation: The Danzig Mennonite Church: Its Origin and History from 1569-1919. North Newton, KS: Bethel College ; Kitchener, ON: Pandora Press, 2007.)

Mannhardt, Wilhelm. Die Wehrfreiheit der Altpreussischen Mennoniten. Marienburg : im Selbstverlage der Altpreussischen Mennonitengemeinden : in Commission bei B. Hermann Hemmpels Wwe., 1863.

Penner, Horst. Ansiedlung mennonitischer Niederländer im Weichselmündungsgebiet von der Mitte des 16. Jh. bis zum Beginn der Preussischen Zeit. Schriftenreihe des Menn. Gesch.-Ver., No. 3. Weierhof (Pfalz): Mennonitischer Geschichtsverein, 1940.

Penner, Horst. "The Anabaptists and Mennonites of East Prussia,” Mennonite Quarterly Review 22 (1948): 212-25.

J. Gingerich, “Die Mennonitengemeinde Königsberg und ihr Ende." Der Mennonit II (1949): 21 f.

Randt, Erich. Die Mennoniten in Ostpreussen und Litauen bis zum Jahre 1772 Königsberg: Randt, 1912.

Schumacher, Bruno. Niederländische Ansiedlungen im Herzogtum Preussen zur Zeit Herzog Albrechts (1525-1568). Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, 1903.

Unruh, Benjamin Heinrich. "Kolonisatorische Berührungen zwischen den Mennoniten und den Siedlern anderer Konfessionen im Weichselgebiet und in der Neumark." Deutsches Archiv für Landes- und Volksforschung IV (1940): 254-272.

Wermke, Ernst. Bibliographie der Geschichte von Ost- und Westpreussen für die Jahre 1939-1951. Marburg/Lahn : [s.n.], 1953.

Wiebe, Herbert. Das Siedlungswerk niederländischer Mennoniten im Weichseltal zwischen Fordon und Weissenberg bis zum Ausgang des 18. Jahrhunderts. Marburg a.d. Lahn : [s.n.], 1952.

| Author(s) | Horst Penner |

|---|---|

| Date Published | 1955 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Penner, Horst. "East Prussia." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1955. Web. 16 Apr 2024. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=East_Prussia&oldid=102080.

APA style

Penner, Horst. (1955). East Prussia. Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 16 April 2024, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=East_Prussia&oldid=102080.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 2, pp. 123-125. All rights reserved.

©1996-2024 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.