Netherlands

Introduction

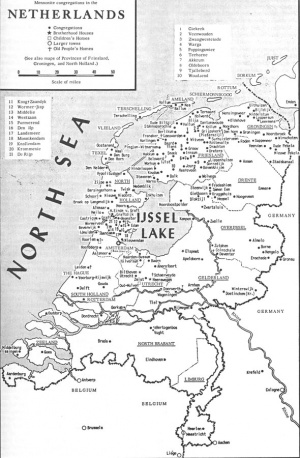

The term Netherlands is here used as it existed geographically and politically in 1957, i.e., without Belgium, but including Limburg, which in the 16th century belonged to Jülich, and also including Ijssel Lake and other coastal inlets. This area, covering 15,765 square miles in 1950, had a population of 9,625,499. In 2005, this had reached 16,297,196.

In the history and life of the Netherlands the Anabaptist-Mennonites have occupied an important place, in the first place by their numbers. Originally they comprised a large segment of the population of the provinces of North Holland, Friesland, and Groningen. In Friesland it has been estimated that they composed one fourth of the entire population. But their importance lay also in their participation in the culture of the Netherlands. Many of Holland's most famous poets and painters, e.g., Carel van Mander, Joost van den Vondel, Antonides van der Goes, Lambert Jacobsz, Ruysdael, Jacob and Adriaen Backer, van Mierevelt, father and son Dirk van Hoogstraten and Samuel van Hoogstraten, were Mennonites. Distinguished scholars in all areas of knowledge, businessmen of note, and top bankers were produced by the Mennonites. After 1795 there were also Mennonites in high official positions. Some of these were cabinet ministers, one of whom was C. Lely, who laid the plans for the reclamation of the Zuiderzee, and others were governors of the Dutch East Indies or mayors of the large cities, as Amsterdam, The Hague, and Haarlem.

But there is still another reason for the importance of the Mennonites in the Netherlands. Whereas in other parts of Europe they were either completely wiped out or after severe persecution reduced to a small percentage of the population, in the Netherlands the Anabaptists, after the first half century of persecution, were permitted to develop in comparative peace and live in accord with their type of faith, their un-dogmatic Christianity, which was true to the Gospel but without binding formulations and was especially strong in its practical aspects.

The Rise of Anabaptism (1530-1556)

The Early Leaders of Anabaptism

It was slightly later than in Switzerland, Germany, Tyrol, and Moravia, that Anabaptism appeared in the Netherlands. In 1530 Jan Volkertsz Trypmaker brought baptism upon confession of faith from Emden to the Netherlands. He had there come in contact with Melchior Hoffman, a chiliast and Anabaptist Reformer, who had shortly before united with the Anabaptists in Strasbourg. In Friesland as well as in Amsterdam Trypmaker's sermons enjoyed a large following, while elsewhere, as in South Limburg, baptism upon confession of faith found entry into a small circle of friends of the Reformation. The movement spread with great speed; for at that early date there was already evident a growing spirit "of unecclesiastical independence and Biblical renewal of life, which can be best characterized as the Anabaptist spirit" (Kühler).

The fruits could mature here so quickly because the soil was ready for the movement. Even before 1530 there were in the Netherlands many friends of the Reformation, which had developed especially from the circles of the Devotio Moderna and their acquaintance with the Bible. It was in these circles that the preaching of Trypmaker and others was to crystallize baptism upon confession of faith as an external symbol into an Anabaptist church or brotherhood. Many of these congregations must have reached a large membership within a few months. Men like Obbe Philips, who was the leader of a large congregation at Leeuwarden in Friesland, and Jacob van Campen, who died as a martyr at Amsterdam in 1535, were a strong support. An eager expectation of the imminent kingdom of God prevailed. Hoffman's visits in the Netherlands (1531, 1532) and his writings had further strengthened these expectations. Those who were converted were baptized (the ceremony was simply the expression of the personal connection with God), and then patiently awaited the coming of the kingdom, living true to the evangelical demands of non-vengeance, non-swearing of oaths, uprightness, and love of one's neighbor.

Persecutions

The imperial government at Brussels, and Charles V most of all, viewed the increasing decline of Catholicism and the growth of the Anabaptist movement with deep disfavor. Various proclamations were issued, beginning in 1521, against the spread of the Reformation. The proclamation of 10 June 1535 opposed the Anabaptists exclusively. It was of extreme severity and announced that anyone who refused to recant, who had re-baptized others, or who claimed to be a prophet, apostle, or bishop, would be sentenced to death by fire; any who were re-baptized but recanted, or who harbored Anabaptists, would be sentenced to death by beheading, or in the case of women, by drowning. This threat was repeated through provincial and local authorities. The Frisian Stadholder in 1534 commanded by means of proclamations that "the damned sect of the Anabaptists" be exterminated. Thus the government insisted on severe persecution; nevertheless the authorities of the cities and provinces were reluctant to obey, and sabotaged the supreme commands, often because they were benevolently disposed to the Anabaptists as if they themselves had been members of the group.

But in the long run the Anabaptists met with severity, especially in the imperial crown lands, the provinces of Holland, Zeeland, and in the southern Netherlands. (During this time the emperor acquired all the provinces of the Netherlands: Friesland in 1524, Utrecht 1527, Overijssel 1528, Groningen 1536, Drenthe 1537, Gelderland 1543.) In the recently acquired areas the persecution was in general less severe; Groningen had only one Anabaptist martyr.

The severity reached its height, even the lesser authorities now co-operating, when the Münster episode of violence occurred and Jan van Leyden, who obtained the upper hand in the government of the "new Zion" in 1534, began to make himself felt in the Netherlands. On the whole, it may be said that the Dutch Anabaptists turned away from these horrors. A meeting of thirty-two Anabaptist leaders held at Spaarndam, near Haarlem, at the end of 1534 or early in 1535, for the most part repudiated all violence. Obbe Philips had broken completely with the violent element by 1534. But many Anabaptists, incited by interminable persecution, weary of passively waiting for the kingdom of God, lent an ear to the commands of the sly seducer to come to Münster, or fell into the trap of his criminal emissary Jan van Geelen. Then when there were riots even in the Netherlands, i.e., the seizure of the Oldeklooster by a troop of revolutionary Anabaptists (30 March 1535) and the attack on the city hall of Amsterdam (10 May 1535), and other acts of violence here and there, the mania of persecution knew no bounds. Revolutionary and peaceful Anabaptists were lumped together into one class, although the authorities knew very well that there was a great difference between them, and that the latter had no other desire than to avoid all violence and in faithfulness to the Gospel to await the coming of the Lord. Men and women fared like Jan Pauw, who said his heart did not testify to him to defend himself with a knife (beheaded 6 March 1535).

On 25 June 1535, Münster fell; Jan van Leyden's wicked role as king was finished, his unholy influence on the movement in the Netherlands ended. But for several years the revolutionary followers of Jan van Batenburg made the country unsafe and brought ill fame upon the peaceable Anabaptists, who would have nothing to do with him.

The persecutions continued to claim many martyrs. It has never been possible to determine their exact number. Kühler's estimate of about 1,500 is too low; 2,500 is probably more nearly correct. In the northern Netherlands Reytse Aysesz was the last to lay down his life for his faith. He was executed at Leeuwarden on 23 April 1574. In the South the last martyr was executed at Brussels in 1597. (See Anneken vanden Hove)

Organization of the Congregations

At places Anabaptism was completely rooted out; e.g., at Maastricht and in the entire province of Limburg; elsewhere the movement persisted, and in these congregations a firm organization and church discipline arose concerning preaching, baptism, and the Lord's Supper. Of great importance was the fearlessness of the elders, who in almost complete disregard of danger—they were, of course, most sought after by the police—traveled about the country to preach and to serve with baptism and communion. Obbe Philips had been baptized by Bartel (Bartholomeus) Boeckbinder. In 1534-1536, the period of great difficulty, he had powerfully opposed all violence and ordained both his brother Dirk Philips and Menno Simons as elders. Although he grew discontented and withdrew from the brotherhood as early as 1540, his work must be remembered with gratitude. Other men took his place, especially Menno Simons, who had left the Catholic priesthood in January 1536, and after a period of quiet study of the Bible began in 1539, both by word of mouth and in writing, his task as the leader of the Dutch Anabaptists. In December 1542 a price was set on his head, in consequence of which he had to live outside the country. He stayed successively in East Friesland, the Rhineland, Wismar, and in his last years at Wüstenfelde, near Oldesloe. Dirk Philips also lived outside the Netherlands, at Danzig. But both of these elders made frequent journeys for longer or shorter periods to the Netherlands, and in addition strengthened the believers through writing. Menno died in 1561, Dirk in 1568.

Other elders continued their work. The most influential of these was Leenaert Bouwens, elder from 1553, who with great zeal promoted the spread and strengthening of the brotherhood, and whose baptismal lists still bear witness of his indefatigable work; he baptized over 10,000 persons in 1551-1582.

Thus the brotherhood seemed to be facing a promising and great future; the severe persecution did not prevent its spread; the Münsterite danger was past. David Joris, ordained as elder by Obbe Philips in 1535, but motivated by ambition rather than love for the Gospel, arrived at the doctrine that it is possible to conform to the world. He was opposed by Menno (1539 ff.) by means of the principles of the Gospel and finally sought refuge in Basel (1556), but continued contacts with his followers in the Netherlands.

Differences Within the Congregations

Even though dangers from without had subsided, quarrels arose within the very circle of the brotherhood. In 1547 Adam Pastor, an elder, was excommunicated on account of deviating views on the Trinity. On this occasion Dirk Philips and Menno Simons assumed the authority to ban, which properly belonged to the brotherhood. This was a basic alteration that became more and more incisive: Is the first authority the individual or the congregation? Finally the great conflict in Menno's life came, which had its basis in this question. Here a disparity of views among the Anabaptists became evident, which had actually existed from the very beginning and is still noticeable among the Dutch Mennonites. Whereas some experienced faith as a personal and inner relationship with God, considered baptism as a personal union between their conscience and God, knew nothing of dominant position either of the congregation or of the elders, wanted to make only a lenient use of the ban, and were disinclined to any formulating of the faith because they feared that the word of man might acquire more respect and power than the Word of God (in general the Spiritualist position), others held fast to the concept of the visible church as a church without spot or wrinkle, in which every individual subjected himself to the common brotherhood, recognized and desired the authority of the elders who would govern the congregation and apply the ban strictly against the unworthy and unbelieving, and demanded a firm system of doctrine expressed in a confession of faith, which to be sure never acquired complete authority as in other churches but was nevertheless of great authority and a means of separating the worthy from the unworthy. The latter party was in the majority.

The Period 1557-1664

Ban and Avoidance

In 1556 the strife flared up. Menno, who had at first taken a very moderate course in the application of the ban, now adopted a stricter course in compliance with the wishes of Dirk Philips and especially of Leenaert Bouwens. The section of the brotherhood that opposed them, the moderate wing, withdrew and were called Franekeraars or Scheedemakers (after their elder Jacob Jansz Scheedemaker), but were most generally called Waterlanders because they had a large following in Waterland of North Holland. Fortunately the strife did not reach the point of banning one another, but the cleavage that had been revealed was not easy to bridge over.

Separation from the German Congregations

Division also arose between the Dutch and the German elders. Besides Menno's strict views of the ban, his doctrine of the Incarnation of Christ was the cause of a division which was completed at a large conference of German Anabaptists at Strasbourg in 1557. This was the beginning of the divisions in the brotherhood, which was still suffering persecution, one such division following upon the other, so that an opponent could speak with a measure of correctness of a "Babel of Anabaptists."

Rise of the Waterlanders

The Waterlanders quietly built up their brotherhood, in which there was no place for dominating elders; they soon achieved a regulated, organized congregational life and an arrangement for mutual assistance in preaching. Excellent men served their congregations: Hans de Ries, Cornelis Anslo, Anthony Roscius, etc. Most of the Waterlander congregations were in the province of North Holland, but they had some congregations in other areas, some as far away as Belgium. They were the more progressive of the Anabaptists, but not liberal in the 19th-century sense of Modernism. They held to a strictly Biblical concept of preaching and faith, and among them was found a deep mystical conception of Christ. They were liberal in the sense that they were less conservative than the other wings, less firmly bound to tradition in clothing and church government. They were also peaceable toward the Frisians and Flemish as well as to the Remonstrants, Collegiants, and even the Catholics. Strange to say, it was these liberal Waterlanders who formulated the first confession of faith (1577), which was, however, by no means to be a binding rule of faith. The liberality in the lines drawn in this confession is significant. They recognized as true members of the church of Jesus Christ all men on earth who had achieved a renewal of the inner man through the power of God through faith. These Waterlanders called themselves Doopsgezinden, not Mennonites. They did not want to be named after a man.

Division Between Frisians and Flemish

Ten years after the first division a second one arose among the Dutch Mennonites (1566). Again Franeker was the scene of the conflict. Here as elsewhere a number of Flemish had settled to escape severe oppression in Flanders. The difference in their manner of life, customs, and habits led to conflicts between them and the Frisians. A number of minor personal differences of opinion and increasing opposition between the two most powerful elders, Dirk Philips and Leenaert Bouwens, the former on the side of the Flemish and the latter on the side of the Frisians, were factors in the impasse reached when Jan Willemsz and Lubbert Gerritsz, who had been called as outside mediator (buitenmannen) to settle the dispute, could not achieve more than a compromise. No lasting results were achieved, and the rupture broke open again. The Frisians and the Flemish banned each other in 1567. Later attempts at reconciliation such as the Peace of Humsterland of 1574 were a complete failure.

But this was not the end of divisions. Twenty years later there was a third flare-up in Franeker Among the Flemish were Thomas Bintgens and his followers (Huiskoopers), opposed by Jacob Keest (Contra-Huiskoopers). At the bottom of this dispute about the purchase of a house lay a deeper conflict between the more conservative and the more moderate elements. Attempts to preserve unity failed, and soon the Flemish were divided into two camps. Not only in Franeker, but everywhere, even among the Mennonites who were not of Flemish origin, there were the Huiskoopers, usually called Old Flemish, and Contra-Huiskoopers, usually called Flemish or "Soft" Flemish.

The Old Flemish, the more conservative, banned from their midst the Vermeulensvolk or Bankrottiers in 1593, and soon afterward the Borstentasters, who, however, soon returned or dissolved. Here and there small groups split off from the Old Flemish, but these also soon reunited with the larger group or died out.

In 1628 and the following years the Groningen Old Flemish divided from the (Soft) Flemish (in 1637 there was another division among the Groningen Old Flemish) on the grounds that the latter permitted mixed marriages and were lax in their application of the ban and avoidance. The Groningen Old Flemish were extremely conservative in clothing and home furnishings. They long practiced feetwashing. Most of their following was in the province of Groningen and they were a closely knit brotherhood. Men like Jan Luies and Uko Wailes (who was banished by the government on account of his peculiar views on Judas, and upon his return banished again in 1644) had great influence among them. The Danzig Old Flemish were just as conservative as the Groningen Old Flemish, but differed from them in the practice of feetwashing in that only elders and visitors from a distance took part.

Nor did the Frisians avoid divisions. In 1589 the stricter ones, soon called Old Frisians, banned Lubbert Gerrilsz, who became the leader of the Young Frisians. A special group of the Old Frisians were the Jan-jacobsgezinden, split off in 1598, named after Jan Jacobsz, who had a considerable following in Friesland and also at Hoorn and Amsterdam. Their last congregation, on Ameland, united with the other local congregations in 1855.

Attempts to Unify

The continuing separations were certainly not favorable to the welfare of the brotherhood. Some, who believed that the church of God could not exist where there were so many divisions, turned their backs to the brotherhood. Others, of all parties except the extreme Old Flemish and Old Frisians, insisted upon reunion. As early as 1591 most of Young Frisians and High Germans united. Before the merger an agreement was drawn up known as the Concept of Cologne. Soon, especially upon the insistence of Hans de Ries, many Waterlanders joined the union, which became known as the Satisfied Brotherhood (see Bevredigde Broederschap). A new spirit arose among the Mennonites. To be sure a request of the Satisfied in 1603 to the Frisians and Flemish to merge had no success; on the contrary, about 1613 a large number of Young Frisians and High Germans separated from the Satisfied Brotherhood (see Afgedeelden) under the leadership of Leenaert Clock; but the wish for unity had after all made itself felt.

About 1610 the Frisian and Flemish congregations in Harlingen united. Also in 1626 four preachers of the Flemish congregation in Amsterdam sent their confession, the Olijftacxken (Olive Branch), as an overture of peace to "the dear brethren, ministers, and elders of the congregations in Groningen, Friesland, Overijssel, Utrecht, Haarlem, and Zeeland." In 1630 an agreement was actually reached between the Flemish on one side and the United Frisians and High Germans on the other. The United Frisians and High Germans had also drawn up a confession for this purpose, named after Jan Cents. This beginning of an agreement led in 1639 to a complete unification of the two branches. The Olijftacxken was also very successful. In 1632 most of the Old Flemish united with the Flemish, on the basis, of the Confession of Adriaen Cornelis, also called the Dordrecht Confession because the conference had been held at Dordrecht. There were still remaining apart the group of the Old Frisians and several congregations of the Old Flemish; likewise the Groningen and Danzig Old Flemish pursued their former course; the others had now found their way to each other.

Only the Waterlanders were still standing to one side, for no fault of their own. Although their great leader Hans de Ries died in 1638 his spirit remained among them, which constantly worked in the direction of unification. In 1626 the Flemish had not offered their Olive Branch to the Waterlanders, perhaps because the differences were too great. There were indeed deep differences between them. The Flemish were more dogmatic and the Waterlanders not at all so; their confessions stressed faith much more than theology. The Waterlanders, who wanted to be bound only to the Holy Scriptures, viewed with concern the authoritarian position of the Olijftacxken. In addition there were differences in church regulations. The Waterlanders observed communion seated around a table, the Flemish while at their seats. Nevertheless the Waterlanders in their conference of 1647 decided to offer Christian peace to the others. The Flemish reply, which was not given until 1649, was negative: if the Waterlanders really wanted peace they would have to begin to adapt themselves in life and teaching to the other Mennonites. Thus the general unification remained a pious wish.

Lamists and Zonists

Soon a new division was to rock the brotherhood. It occurred in the same church, bij 't Lam, at Amsterdam where on 26 April 1639 the reunification of the Frisian and Flemish was so joyfully celebrated, and where two of the preachers in 1664 were Galenus Abrahamsz de Haan and Samuel Apostool. The latter was a man of the old type in whom there was still something of the idea that the Mennonite Church was the only true church, and who devoted all his preaching activity to the strengthening of this idea and insisted on a fixed confession. Galenus, on the other hand, in consequence of his association with the Collegiants and his leading role in peace meetings, was more liberal and warned against attaching too much value to the visible church. Both had a following. After much conflict mockingly called the "Lammerenkrijgh" (War of the Lambs) a schism occurred in 1664. Apostool with 500 members moved into a new meetinghouse, called "de Zon" (the Sun); Galenus with his following stayed "bij' t Lam." And so the more liberal Lamists stood opposed to the more conservative Zonists. This opposition was not confined to Amsterdam; the schism reached all of the Netherlands. And even if the quarrel had lost the violence of the former days, nevertheless any opportunity to achieve unity was destroyed for two centuries. The old partisan designations "Frisian" and "Flemish" disappeared in this new quarrel. Several remnants of the Old Frisians or Old Flemish remained by themselves, but gradually either united with the Zonists or disappeared. But most of the Waterlanders soon united with the Lamists, in Amsterdam already in 1668, and in many places soon afterward. From now on two types of Mennonites were referred to, viz., the Fijne (Fine) Mennisten (Groningen and Danzig Old Flemish, Janjacobsgezinden, etc.) and the Groove (Coarse) Mennisten (Lamists, Zonists, and Waterlanders). Thus the period of 1557-1664 was a time of division, approach, and new division.

Attempts by the State Church to Suppress the Mennonites in Spite of General Toleration

Many changes took place in the mutual relationships between church and state and also in the internal organization of the Dutch Mennonite church. At the beginning of this period bloody persecution still dominated. This ended with the coming of the Eighty Years' War (the war of liberation from Spain 1568-1648) and the rise of Calvinism in the Netherlands. To be sure there were among the Calvinists some who wished to continue the previous proceedings against the Anabaptists; but William of Orange, who was becoming a more and more powerful leader in the revolt against Spain, emphatically opposed them; he wanted toleration. When the Mennonites at Middelburg had difficulties with the authorities established by the Calvinistic preachers, he defended them and secured for them release from the oath and military service. The Union of Utrecht (1579) designated that no one was to be persecuted for his faith. But the Reformed, as the followers of Calvin's doctrine called themselves in the Netherlands, and especially their preachers, tried with all the means at their disposal to interfere with the liberty of the Mennonites to confess their faith freely. In the first place came a long series of violent polemics against the Mennonites, to which the Mennonites replied in writing. But also the synods, especially the provincial ones, sometimes demanded severe measures against the Anabaptists, for which however they usually found no hearing. Looking through their fingers the magistrates tolerated the Anabaptists and saw to it that Calvinistic intolerance would not oppress "our best citizens." On several occasions the building of a Mennonite church was temporarily prevented, as at Franeker in 1611, at Haarlem in 1626, and at Leeuwarden in 1631. The frequent interference of the Reformed preachers in the worship services of the Mennonites was odious, but their attempts to convert the Mennonites failed. Several times the Mennonites had religious disputations with the Reformed clergy, such as the debate by Peter van Coelen with Ruardus Acronius at Leeuwarden in 1596. But these debates were soon abandoned, since the authorities regarded them with disfavor and a number of times forbade them.

Difficulties with the government on the oath and military duty occurred repeatedly, even after the intervention of Prince William in Middelburg, whereas Prince Maurice followed his father's attitude. But these differences did not lead to oppression. The Anabaptists generally obtained the rights of citizenship, substituting a vow "by manly truth" for the oath.

The release from the bearing of arms was obtained by paying a fee or a poll tax and fulfilling their obligation to the government in special services, such as providing food, extinguishing fires, and digging trenches. There was also some difficulty with regard to marriage. Mennonite marriages were usually concluded before the secular authorities, after the bans had been published three times in a Reformed church service. Here and there rules were passed excluding Mennonite children from inheritance, but very likely these severe rulings were only laxly enforced.

Gradually the attitude of the government to the Anabaptists changed. This change has been recorded in two resolutions: in 1583 the "Closer Union" of Utrecht states that the Reformed religion is to be maintained and perfected in the United provinces, "without permitting public instruction . . . for several other religions in the presently united provinces." On the basis of this regulation the Reformed preachers considered it their right to annoy the Mennonites and to prejudice the government against them. The regulation passed in 1651 even designated that "the sects and religious parties" which were excluded from the public protection and are merely tolerated were to hold their services in all quietness, and only in the places where they had previously held their meetings. Both of these resolutions were occasionally seized upon by the Reformed Church to annoy the Mennonite congregations, as happened at Sneek in 1601, but on the whole the Mennonites were able to live and worship relatively undisturbed.

Now the motive of the Reformed in interfering was a different one: the charge that many heresies were being taught among the Mennonites, such as "the horrible error of Socinus" (q.v.). Actually the Mennonites, never having been theologians, were not always immune to the Socinian opposition to the doctrine of the Trinity, the Satisfaction of the Atonement, and other questions.

Participation in the Civil Life of the State

Although the attitude of the government toward the Mennonites had changed (however, the stain of Münster still clung to them in the eyes of the state), the attitude of the Mennonites to the state also underwent a profound change. Good friends of the fatherland, thankful for the ground upon which they lived and for the protection they received —this they had always wanted to be, even when their principles forbade active participation in the conflict with national enemies. Already in 1574 a large sum of money was presented to Prince William in his military camp at Roermond in the name of the Mennonites. In 1666 and again in 1672 the Mennonites raised large loans which made it possible for the state to carry on its war with four foes. In Friesland in 1666, 500,000 guilders was raised, in 1672 again 400,000 guilders, and in 1673 again a significant sum was raised. This assistance more than anything else added to the appreciation for the Mennonites by the state and the public.

Much earlier than this the Mennonites of the Netherlands had been aware of a task in this world. When their expectation of the coming kingdom was not fulfilled, their attention gradually shifted more to this world. An appreciation of the national community, the state, culture, and art, arose, first among the Waterlanders. By 1581 the Waterlanders permitted their members to hold government offices, and after that time many of this branch held such offices. They did not shut their congregations off from the world; Joost van den Vondel, a poet and dramatist, felt himself at home among them and served the Amsterdam Waterlander congregation as deacon. Hans de Ries was a friend of the humanist Dirk Volkertsz Coornhert, whom Kühler called the Sebastian Franck of the Netherlands, and was strongly influenced by him. But the fact that a Carel van Mander could be a member of the Old Flemish group (1602) shows that a change was in progress here too. The fact that among the Mennonites, with the exception of the extreme groups, there was strong sympathy for the Remonstrants, who were likewise under persecution by the Reformed Church, speaks for itself. This sympathy was mutual; the Remonstrants at first used Hans de Ries' confession of faith. On the other hand, when the Remonstrants at Rotterdam proposed a union with the Waterlander Mennonites, objections arose. The Flemish now also began to be more open to the world and seemed to be receptive to Socinianism, for which their Elder Jacques Outerman had to answer to the authorities in 1626. Finally during this time the Flemish as well as the Waterlanders took part in the Collegiant movement; their free-speaking meetings were frequently held in Mennonite meetinghouses.

The First Historical Writings

However great the changes had been, the bonds with the past remained. This is shown by the interest in the martyrs. In the very earliest time testimonies and songs about the martyrs were loyally gathered and by 1599 had been published at least eleven times (first in 1562) in the Offer des Heeren. In 1615 Hans de Ries published a new Historic der Martelaren (History of the Martyrs), which appeared in a second edition in 1631 under the title Martelaers-Spiegel (Martyrs' Mirror), the first use of this title in Mennonite literature. The Old Frisians, who considered themselves the true spiritual descendants of Menno Simons and were unable to accept such a work by the Waterlanders whom they did not regard as true Mennonites, published a new edition of this work in 1617 under the title Historie der Warachtige Getuygen (History of the Genuine Witnesses), with some additions, but without the important foreword by Hans de Ries, substituting for it a confession of faith. It also enjoyed a second edition in 1626 under the title Historie van de Vrome Getuygen (History of the Pious Witnesses), in which the "unorthodoxies" in the martyr book of 1617, which they had thoughtlessly accepted from the book of 1615, were now corrected. Then T. J. van Braght, preacher of the Dordrecht congregation, published in 1660 his Het Bloedig Tooneel der Doopsgezinde en Weerloose Christenen (The Bloody Theater of the Mennonite and Nonresistant Christians), which was reprinted in 1685 with Jan Luiken's etchings under the somewhat modified title Het Bloedig Tooneel of Martelaers Spiegel (The Bloody Theater or Martyrs Mirror).

The Period of Decline, 1665-1810

Differences Between the Lamists and the Zonists

Very soon after the division between the Lamists and the Zonists occurred, attempts were made to heal the breach (1672, 1684, 1685, 1691), but in vain. To be sure, the other small schismatic groups merged again into the larger streams, but the two main streams, Lamists and Zonists, remained separate throughout the 18th century, with opposite courses. The Lamists, often called the "Coarse," paid little attention to doctrinal confessions, were rather free in their attitude toward tradition, and had much association with the Collegiants and the Remonstrants. Even though some nuances were evident, they were mostly Spiritualists advocating an individual concept of faith, with the congregation occupying a secondary place. The Zonists, on the other hand, preferred to call themselves Mennists or Mennonites, as if they were still on the platform of Menno Simons. They had a very high regard for the authority of the congregation, held fast to the ban even though perhaps more in name than in actuality, and laid great stress on the extant confessions of faith; even not rarely leaning toward confessionalism. In 1665 they published De Algemeene Belijdenissen (General Confessions; i.e., Concept of Cologne, Outerman's Confession, Olyftack, Jan Cents' Confession, and Dordrecht Confession). Shortly after this a somewhat surprising trend to confessionalism is found among the Waterlanders; some of them forsook their spiritualism, and now stressed the confession of Hans de Ries, and many of their congregations, particularly in the province of North Holland, joined the Zonist Conference. Again about 1750 there was among the Dutch Mennonites an unusual interest in confessions. The Danzig Old Flemish produced one in 1743, the Groningen Old Flemish Conference (Sociëteit) one in 1755. Neither group had ever before drawn up a confession. The Zonist Conference in 1766 approved a confession drawn up for them by Cornelis Ris. This confession, however, never came into general use among the Dutch Mennonites. Many of the Zonists, except for adult baptism, felt themselves more closely related to the Reformed Church than with their brethren in the Lamist camp. In the final period of the 18th century not only did many of them transfer their membership to the Reformed Church, but in 1766 the preachers Cornelis Ris and Jan Beets at Hoorn actually promoted the idea of a union with the Reformed.

Readiness to Help the Needy

However different, even hostile, some of the Dutch Mennonites of this time were to one another, in one matter they always cooperated harmoniously, namely, when aid was asked for oppressed or suffering brethren. How frequently this aid was asked! In 1671 they helped their brethren in the Palatinate. The sum of 20,000 guilders was raised to support the refugees who came to Krefeld and Groningen. In 1711 one hundred Swiss families came to the Netherlands, followed by others in 1713, for whom land and homes had to be procured. For this purpose the sum of 30,000 guilders was raised in 1711, and another large sum in 1713. Likewise in 1713 they helped the Mennonites in Prussia and Poland. For this work a permanent committee was established, the Committee for Foreign Needs (see Fonds voor Buitenlandsche Nooden) which had a definite fund after 1725. In 1732 they were able to provide shelter for more than 100 persons who had come from the Danzig area to the island of Walcheren and to Wageningen. Until 1790 occasional collections were raised for the Mennonites of Poland and Lithuania, who suffered from floods and other calamities. The Committee was dissolved in 1804; but occasionally relief was still given, as in 1886 for the Mennonites in the Marienburg Werder in Prussia, who had suffered severe losses by floods, and especially after 1920 for the Russian Mennonites. Not only were those of the "household of faith," the Mennonites in various countries, financially supported by the Dutch Mennonites, but also others; e.g., Waldensians, the Salzburg refugees, Polish Unitarians, and also many Reformed.

Forming Conferences

Schisms and strife had caused many to leave the brotherhood. There was reason for concern for the future. Discipline grew visibly lax. In 1700 the United Flemish and Waterlander congregation at Rotterdam invited all Christians to communion, with no question as to whether they had been baptized as adults. Small congregations were no longer entirely self-supporting and threatened to die out. Mutual assistance was necessary. Out of this need various conferences (Sociëteit) arose. Among the stricter Mennonites these conferences at first served to provide supervision of the teaching doctrine and discipline.

The Waterlanders seem to have been the first to recognize the need of common consultations. As early as 1568 their delegates met, meeting again in 1581, 1618, and 1647. Also the Groningen Old Flemish (25 congregations in Groningen, 10 in Friesland, 4 in Holland, and 5 in East Friesland) had apparently met regularly in the first half of the 17th century. This developed into the Groningen Old Flemish Sociëteit. Although in the later period this conference no longer met regularly and many congregations outside the province dropped their membership in it, it existed until 1815. Beside this first sociëteit there was a second in the province of Groningen, the Humsterland Sociëteit, which originally embraced 10 congregations in Groningen and Friesland. It existed until 1825.

In North Holland the Frisian congregations had in all probability also united into a conference in the first half of the 17th century. This Frisian Sociëteit met regularly until 1818, but dissolved in 1841 into the Rijper Sociëteit. This latter (Waterlander) Sociëteit had been meeting since about 1640. A noticeable characteristic of this conference was the fact that whereas all the other conferences consisted of preachers and deacons, the Rijper Societeit held two meetings, one for the preachers and one for the deacons. The former was discontinued in the late 18th century; in the 1950s the deacons met regularly in De Rijp.

In 1675 the delegates of the Lamist congregations of South Holland met (the Amsterdam and Haarlem congregations also belonged to this conference). This conference also gave the initiative for the founding of the Sociëteit of Friesland, which united a large number of Mennonite congregations in this province and until 1791 also included three congregations in the province of Groningen. The Sociëteit of Friesland met for the first time in 1695. It was still in existence in the 1950s, all the 47 congregations in the province of Friesland being members.

In addition a Zonist Sociëteit arose in 1674. The first objective of this conference was the application of the confession of faith. In 1674 it issued the Grondsteen van vreede en verdraegsaemheyt tot opbouwinge van den tempel Christi onder de Doopsgezinde (Foundation Stone of Peace and Tolerance for the Building of the Temple of Christ among the Mennonites). Some Waterlander congregations joined it. An attempted union with the Frisian Sociëteit in North Holland failed in 1723. Nor did a planned merger with the Groningen Old Flemish Sociëteit in 1766 succeed. The Zonist Sociëteit met until 1796 when the Amsterdam congregation dropped its membership. These conferences not only benefited the congregations by preventing their disintegration, using the means of mutual support, but they also brought together like-minded groups.

There were many changes in church life in the 18th century. The office of elder, as the one who alone could administer baptism and communion, gradually fell into decline. It was maintained longest among the Groningen Old Flemish (until 1749). Everywhere else local ministers also administered baptism and communion; their burdens were thereby increased. In many instances these brethren, chosen from the congregation, of whose piety there was no question but whose education was slight, did not feel equal to the task. There are reports that they were less competent than the Reformed and Remonstrant preachers and that therefore many members left the Mennonite congregations. In addition, the love for the office of preaching was decreasing, so that congregations that had formerly had four to six preachers now had none. A desire arose for more educated preachers. An early solution to the problem was to choose for the ministry men who had studied medicine and therefore had some scholarly training. Examples of such physician-preachers were Anthony Roscius, who died in 1616 at an early age; Jan Willemsz in De Rijp (b. 1587); Galenus Abrahamsz de Haan, who assumed the ministerial service in the Lamist congregation in Amsterdam d. 1706); the Zonist preacher and historian Herman Schijn (d. 1727); and Gerardus Maatschoen (d. 1751). But the congregations wanted more. Especially in the conference of South Holland the question of theologically trained preachers arose a number of times. Galenus Abrahamsz offered to give special training, and the Lam en Toren congregation at Amsterdam paid the expenses. So Galenus began his activity in 1680, serving until 1703. The church board was unable to find a successor for him when he retired. Oncoming preachers now had to study under Remonstrant professors in order to follow the lectures at the Remonstrant seminary, which had existed at Amsterdam since 1639. But when this practice issued in Remonstrant graduates being called to Mennonite congregations, while there was a dearth of preachers among the Remonstrants and furthermore when difficulty arose between the Mennonites and the Remonstrants on the question of baptism, the Amsterdam Mennonite congregation decided to establish its own seminary. Attempts to interest the entire brotherhood in this project failed. The cooperation of other congregations was very slight, and the Zonists had doubts and objections. In 1735 Tjerk Nieuwenhuis became a professor of the seminary; he was succeeded by Heere Oosterbaan and Gerrit Hesselink. The seminary soon thrived.

The Zonists also took steps to this end. Their conference in 1733 appointed their Amsterdam preacher Petrus Smidt as professor. Many oncoming preachers, however, continued to receive their training from other preachers, who made it one of their tasks to lead young people into the office of the ministry.

Still, all of these measures were not sufficient to halt the steady decline in membership. Whereas in the 17th century the small conservative groups sometimes disappeared unnoticed, now the main groups also declined in number, as the membership in almost all of the congregations decreased. In Haarlem the number of baptized Mennonites decreased from about 3,000 in 1708 to 488 in 1834; in Hoorn, where in 1695 there were about 450 Mennonites, the number decreased to 212 in 1747 and 119 in 1845. Vlissingen dropped from 230 members in 1660 to 99 in 1757 and 22 in 1834. In Friesland, where there had been some 20,000 members in 1666, the number fell below 13,000 in 1796; one third of the members had been lost since 1739. It was still worse in South Holland. Of the 27 congregations in existence there at the end of the 18th century only three remained—Leiden, Ouddorp, and Rotterdam. Whereas the number of Mennonites in the Netherlands in 1700 was still estimated at 160,000 souls, in 1808 there were only 26,953. From 1700 to 1800 exactly 100 Dutch Mennonite congregations disappeared. In 1837 there were only 15,326 baptized Mennonites in Holland.

What were the reasons for this decline? The general decline in interest that eventuated in indifference is striking. But specific causes of various kinds can also be given. The Mennonite congregations around the Zuiderzee, e.g., Hoorn, Makkum, Hindelopen, Molkwerum, were the victims of the economic decay of these towns when the thriving Baltic trade disappeared. Many Mennonites were no longer satisfied with the occasionally very simple sermons of the lay preachers, and sought edification with the Remonstrants and the Reformed. Others—and their number was not small—went over to the established church in order to procure for themselves and their descendants the right to accept honorable government positions. Increasing wealth and luxury, about which Galenus Abrahamsz had already complained, also led to indifference on the part of many. Some who were unhappy in the separation of church life from the general life of the country went to the free-speaking meetings of the Rijnsburger Collegiants; but these also declined from the middle of the 18th century. Led by the new spirit of the Enlightenment, and influenced by the current literature, Mennonites of this type finally turned their backs on the brotherhood altogether.

Finally, the Reformed clergy was still watchful against heresy, even though not with the same violence as in former times, attacking especially Socinianism, which they thought they saw—and sometimes not mistakenly—in the Mennonites. Real Socinianism, however, passed over into a wider liberalism. In 1722 a doctrinal formula was drawn up for Mennonite preachers in Friesland to sign, which was to determine their orthodoxy. All but one refused to comply, not primarily because they were sympathetic to liberalism, but because they considered the signing of such a formula as un-Mennonite. For the time being the matter remained quiescent, but finally the Reformed clergy managed to have the capable preacher Johannes Stinstra at Harlingen deposed from his office by the government of Friesland on the grounds of heresy, and required to remain inactive until 1757.

But aside from these and a few other instances, the Dutch government was benevolent in its attitude. As early as 1671 bequests could be made for the Mennonite poor in Amsterdam. In Friesland—here and in the province of Zeeland the Mennonites had most to suffer from the hostility of the Reformed clergy—a bequest to the Molkwerum congregation was still forbidden in 1705, and in Witmarsum until 1753. Even though full legal equality was not attained until 1796, in many respects the magistrate came to the defense of the Mennonites. Thus it was gradually found satisfactory to have Mennonite marriages solemnized before their own congregations, provided the governments were notified beforehand or within a definite period afterward. Since the time of the Batavian Republic (1796) civil marriages have been obligatory for all persons in the Netherlands including Mennonites.

Relaxation of Church Regulations

The ancient landmarks of the brotherhood gradually fell into decay. Mixed marriages (with someone outside the brotherhood), which had in the previous period been the occasion for much strife, were, to be sure, still forbidden by the "Fine" Mennonites, but for the most part nothing happened if a Mennonite married a non-Mennonite. Also the ban, at least the "great ban," in which the church member was excommunicated from the congregation, hardly ever was used after the mid-18th century. But the small ban, which meant exclusion from communion until correction of the error, was still applied, e.g., when young men sailed on armed boats. About 1765 a woman was refused communion at Terhorne because she was wearing a gold cap. In 1701 (records of the Frisian Sociëteit in North Holland) there was some complaint that decline was taking place in the attitude on mixed marriage, the ban, feetwashing, and the furnishing of or sailing on boats with arms.

Especially in the principle against bearing arms was there laxity of application. The doctrine was defended in books, and now and then the ban was pronounced against an offender (in Texel as late as 1793), and the Zonist Sociëteit called the bearing of arms "a deviation from the Mennonite principles," but the doctrine was less and less regarded. After 1784 many Mennonites, especially in North Holland, enrolled in the militia, although this practice was by no means generally approved. In 1799, when the old Mennonite privilege of release from the bearing of arms was canceled, there was no general movement of protest. Only a few congregations complained. Upon a petition of the congregations of Haarlem and Rotterdam made to Louis Napoleon in 1806 this privilege was restored, but when the Netherlands was incorporated into France in 1810 it was again abrogated. The issue did not become acute until the introduction of compulsory military service in 1898.

Although the Waterlanders had early broken through the separation of the church from the world, in which the Lamists soon followed, in the 18th century the conservatives tried passionately to keep the church away from the world, but without success. They too had to surrender to the spirit of the time. It is noteworthy that the Zonist hymnal of Amsterdam of 1796 had more of a rationalistic spirit than the hymnal published by the Lamist congregation in 1792. The conservatives were turning about-face; the "liberals" remained true to their genius; the liberals had very early seen the untenability of isolation. Indeed, as noted above, by 1700 the Rotterdam congregation decided to invite all Christians to communion, without requiring adult baptism; the visible church had ceased to be considered a reflection of the kingdom of God. It is characteristic that in 1700 and a few times later some were baptized in the Waterlander congregation at Grouw and other congregations, and "were not received into our brotherhood, but were baptized into the general Christian church." In this, Collegiant influences are clearly discernible. The extent of friendly relations between the Mennonites and the Collegiants here and there is indicated by the fact that in 1715 the two groups in Groningen used the same meetinghouse, Mennonite services being held in the morning and Collegiant services in the afternoon. The Mennonite church council of Zwolle went still further, deciding in 1808 that henceforth baptism as an infant would be accepted as valid in the case of members of the Reformed Church who wished to transfer to the Mennonite congregation. This extreme position also prevailed at other places. In the early 18th century Remonstrant ministers preached at Mennonite services, e.g., in the Waterlander congregation at Leeuwarden. Nevertheless the Mennonites valued their independence; for in 1796 when the Remonstrants circulated among all the ministers of the Protestant churches in the Netherlands a proposal that all unite with them into a single Christian brotherhood all the Mennonite congregations except Dokkum rejected the idea; in Dokkum this union was formed in 1798.

Prayer and Singing

Within the congregation al life there were also many changes. Silent prayer was gradually replaced by audible prayer, the Waterlanders and Lamists having completed the change by 1661. In 1770 silent prayer was still practiced in a number of congregations. Audible prayer was introduced in the Ameland congregations in 1789; the last congregation to hold fast to silent prayer was Aalsmeer, which gave it up in 1867.

In many congregations the singing was now accompanied by an organ. The first organ in a Dutch Mennonite church was installed in the Utrecht Church in 1765; it was followed by Haarlem in 1771, Rotterdam in 1775, Amsterdam bij 't Lam in 1777, and by Zaandam Nieuwe Huis in 1784.

The hymnal also underwent changes (see Hymnology). There had been singing in the Anabaptist-Mennonite churches from very early times, usually Biblical hymns and martyr hymns. Later, numerous collections of hymns were made: Hans de Ries's hymnal of 1582, the various Hoorn hymnals (issued as late as 1732 for the Groningen Old Flemish and the Balk congregation in 1814), Alle Derk's Lusthof des gemoeds with its supplement the Achterhofje, which were used here and there until the 19th century. In addition, some non-Mennonite hymnals were used; e.g., D. R. Camphuizen's Stichtelijcke Rijmen (Devotional Poems) or the much-used Lusthof der Zielen (Pleasure Garden of the Soul) by the Remonstrant notary Claes Stapel of Hoorn. The Psalms in various versions were also sung. Besides the mediocre versification of the Psalms by the Reformed minister Petrus Dathenus, a new translation was introduced in the Lamist church in Amsterdam in 1684, which was replaced in 1770 by the versification by the poetic society Laus Deo, Salus populo, which had been used by the Zonist congregation since 1762. Since 1713 Haarlem had had its own version of the Psalms, which was also used in other congregations. Later also the new Reformed version of 1773 was introduced here and there; and the evangelical Reformed hymns of 1807 and also its supplementary volume were used in many congregations.

Between 1792 and 1811 at least four new hymnals were produced, consisting for the most part of hymns taken from the previous books, viz., 1792 the Kleine Bundel (Lamist Amsterdam), 1796 the Groote Bundel (Zonist Amsterdam), 1805 the Old Haarlem Bundel, 1811 the Uitgezochte Liederen (Leiden and Zaandam-West). These collections were used in other congregations besides the ones they were published for. (See Hymnology.)

Church Architecture

In this period, in which the Mennonites became prosperous, not to say wealthy, new churches were built, even though the government did not permit building in the open. Besides the characteristic frame churches which were built in North Holland and of which a number of beautiful specimens are still standing, e.g., in Krommenie, West-Zaan Zuid, and Zaandam, there were also "barn" churches, like those still standing at Zijldijk and Nes in Ameland. But also larger churches were built in the 18th century, like the splendid church at Rotterdam, which was destroyed on 13 May 1940, during World War II. (See Architecture).

Benevolent Institutions

The economic wellbeing of the Dutch Mennonites was expressed not only in church architecture and equipment, but also in the provisions made for the care of the aged and orphans. By 1630 Gerrit Franken van Hoogmade established the Bethlehem hofje (old people's home) at Leiden, and bequeathed it to the Waterlander congregation. In 1634 Elisabeth van Blenckvliet, the widow of Jaques van Damme, contributed an orphanage to the Flemish congregation of Den Blok in Haarlem. About the same time some other hofjes were established at Amsterdam and Haarlem. The Waterlander congregation of Leeuwarden acquired its Marcelis Goverts Gasthuis in 1669. In the course of the 17th and 18th centuries many congregations, even small ones, acquired hospitals and orphanages, sometimes given by individuals, sometimes built by the congregations. The Flemish congregation at Leiden in 1660 established the Hoeksteen hospital, and the United Flemish and Waterlander congregation at Zaandam built an orphanage. (See Homes for the Aged and Orphanages.) Also the care of the widows of ministers was taken in hand. In 1794 the Rijper Societeit established a fund for this purpose, and in 1804 the Frisian Sociëteit followed suit and others also followed later (see Pensioen Fonds).

But their benevolence was not limited to members of the Dutch Mennonite congregations. The contributions raised for fellow believers in other countries as well as for non-Mennonites, e.g., for the oppressed French Reformed under Louis XIV, have already been mentioned. The contribution of the Dutch Mennonites for the common national welfare has not been slight: the association for the rescue of shipwrecked persons, the fund for the widows of shipwrecked sailors, the seminar for navigation, the Maatschappij tot Nut van't Algemeen founded by Jan Nieuwenhuizen, all were established principally on Mennonite initiative.

Among the many who might be named with honor for their contribution to the common welfare or to scholarship, an outstanding benefactor was Pieter Teyler van der Hulst of Haarlem, who at his death in 1778 bequeathed his property for the establishment of the Teyler Foundation, which supports an excellent museum and has done much for the promotion of scholarship in Holland, especially theology.

Confessional Equality

The political changes in the Netherlands in the last fifteen years of the 18th century were extensive. The whole nation was divided into two parties, the Orangist party and the Patriot party which was strongly influenced by ideas coming from France. Most of the Mennonites joined the Patriots. Even though they did not forget the privileges and the protection which they had always enjoyed at the hands of the House of Orange, they were still only a tolerated sect in comparison with the Reformed Church, and whereas the Reformed clergy and the regents, their natural opponents, were fiery Orangists, it was to be expected that the Mennonites, who as individualists warmly accepted the new French ideas which fitted so well their religious ideal and their true position, should feel quite at home among those who stood for "liberty, equality, and brotherhood." Actually the republic did away with the hated position of inferiority and brought them the desired equality with the Reformed Church. In the National Assembly of 23 May 1796 a resolution was unanimously adopted, "that since religion is now separated from the state there shall no longer be a preferred religion in the free Netherlands."

Founding of the General Mennonite Conference (ADS, i.e., Algemeene Doopsgezinde Sociëteit)

The difficult times which followed did not pass without affecting the life of the brotherhood. One result was the reuniting in 1801 of the two Amsterdam congregations, the Lamist and the Zonist. The general impoverishment of the people also affected the congregations. For instance, through a reduction of the fixed income of pensioners and other causes, the annual income of the Amsterdam congregation was reduced by 34,000 florins. It became impossible for the congregation to maintain the Seminary without outside help. And so in 1811 it finally became possible to accomplish what had been impossible in 1735, namely, the establishment of a general conference (ADS). Almost all the Dutch congregations joined the new conference. The ADS now took on the care of the Seminary and thus continued the work which the Amsterdam congregation had for three quarters of a century carried on alone for the welfare of the whole brotherhood and which had already become such a great blessing to the church. Furthermore the ADS took upon itself the task of financial assistance for the salaries of ministers in the weak congregations. So in 1811 a new era dawned for the Mennonites in the Netherlands.

The Modern Period, 1811-1957

Amsterdam Mennonite Seminary

In the first years of the new era little was accomplished in the new direction. The Mennonite congregations also had to bear their share of the troubles of the French Empire, viz., the large reduction in financial income, and the loss of freedom. The year 1815 brought liberation. Now the new age could begin, which brought about the equalization of the Mennonites with all other denominations, which so many had longed for in the 18th century. During this period practically all the congregations came to the place where they secured preachers who had received scholarly training in the Seminary, but there have always been laymen here and there who carried on the work of preaching without training. Only one congregation, that of the Old Frisians at Balk, refused to join the ADS. The Seminary carried on a work of real blessing. Professor Hesseling died in 1811; Rinse Koopmans was his successor, although he could not begin his work until 1814. After his death two professors were chosen, and since then there have regularly been two. These have been Samuel Muller 1826-1856, W. Cnoop Koopmans 1826-1849, J. van Gilse 1849-1859, S. Hoekstra Bzn 1857-1892, and J. G. de Hoop Scheffer 1860-1890. Hoekstra and de Hoop Scheffer were from 1877 also professors at the University of Amsterdam, which was opened in that year. In that year the instruction in the Seminary was reduced in amount and the students were sent to the university to take their examinations. The later professors were all university professors also: Samuel Cramer 1890-1912, I. J. le Cosquino de Bussy 1892-1916, W. J. Kühler 1912-1946, J. G. Appeldoorn 1916-1933, W. Leendertz 1946-1956, and J. A. Oosterbaan 1956- . Since the death of de Bussy there has been only one professor besides one or two lecturers.

Two of the professors in the Seminary require special mention. The first was Samuel Muller, who was responsible for raising the Seminary to a high level and whose ideal it was to give the Mennonite preachers a scholarly education on a level with that of the older denominations. He brought a new spirit into the brotherhood and gave the impulse to an intensive study of Mennonite history. The second was Sytse Hoekstra, who found (or created) a type of modernism (liberalism) which suited the Dutch Mennonites, and of whom Muller testified that he was "probably the keenest thinker which Holland produced in the 19th century in this field." Mennonite history was taught at the seminary by Muller, de Hoop Scheffer, Cramer, Kühler, and since 1946 by N. van der Zijpp. W. F. Golterman has since 1946 been lecturer in practical theology.

Theological Alignments

Following 1815 there was at first no spiritual revival in the brotherhood. A moderate supernaturalism was in general dominant, which gave due recognition to the Biblical events of salvation, but gave them a strong moralistic interpretation. Men liked to speak about the teachings of the good Jesus. A Christianity of virtue and enlightenment was preached. According to a tract of this time, the intention was to protect from decay the Mennonite body and its concern for a rational knowledge of God, for the general welfare, and for the consideration of virtue and piety. There was as much opposition to the Neology of the time which rejected everything, as there was toward a cheap sort of fanaticism. It was not until 1830 that a fresher spirit appeared; now there was a growing piety; Muller's influence was making itself felt; again preaching had Biblical theology for its content. But in opposition to this other persons arose, such as the Deventer minister J. H. Halbertsma, who advocated a liberal rationalism. But the opposite extreme also affected the brotherhood; the Dutch revival movement known as the Revell found supporters among the Mennonites. Never has a pietistic element been completely missing in the Dutch brotherhood. Among the supporters of the Réveil were Isaac Molenaar, who was a minister in Leiden until 1818 and thereafter in Krefeld; Jan ter Borg, who served in Amsterdam until 1828; Willem de Clercq, who, like Willem Messchert, left the brotherhood. Others were Jan de Liefde, Johannes Molenaar's brother-in-law, who was a preacher in Zutphen until 1846, and Assuerus Doyer, pastor at Zwolle. P. van der Goot, preacher at Rotterdam and 1851-1875 at Amsterdam, was a warm supporter of the Réveil in its later stages. Throughout the 19th century a noticeable pietistic tendency persisted in the Dutch brotherhood and likewise a more theological trend which rallied around Samuel Muller, especially in his later years.

At first, when the modernistic theology arose in the Dutch universities after 1842, the Mennonites were quite cool toward it, holding fast to supernaturalism. However, "under van Gilse the modernistic tendency approached the Seminary, and under Hoekstra and Scheffer in 1857 and 1860 it made its entry" (Cramer). This disturbed many. They wanted to hold fast to the Biblical, historical Christian note in the life of faith. D. S. Gorter, a minister in several village congregations, who was known for his Doopsgezinde Lectuur, wrote in 1856, "But this I know, I do not want to be either liberal or orthodox .. . but only Biblical." Pastor Sybrandy of Haarlem, who also feared a dangerous development, made a proposal in the meeting of the ADS in 1866 that each candidate for ordination should be required to deliver an exposition of the Scripturalness of adult baptism, but the proposal was lost, with eleven of the seventeen votes against it. By no means all of those who voted against it were modernistic; among them there were certainly some who were moved by the fear of an un-Mennonite formalism.

By about 1871 modernism had won a general victory throughout the congregations, but there were still congregations and preachers, such as the ministers Taco Kuiper at Amsterdam and Jan Hartog of Utrecht, who rejected it. The change to modernism in the congregations had not produced many difficulties. Only in the Groningen congregation was there tension when, in 1867, the ministers J. W. Straatman and C. Corver proposed (1) that baptism be made optional, (2) to gradually do away with the communion service, (3) to permit the preachers to omit hymns, prayer, and Scripture from the service, and (4) to give them the privilege of choosing freely the content of their sermons on the major Christian holidays. When their proposals were rejected both pastors resigned. As a result of radical liberalism baptism was abolished in the Midwolda congregation; for a number of years no communion services were held in the Winterswijk and Franeker congregations.

The great majority of the Mennonites were modernistic, but because of Hoekstra's influence they did not usually belong to the radical left wing. Here and there were also quite a number who stood on the "right" as more evangelical. In Amsterdam there was an "Association for the Maintenance of God's Word in the Mennonite Congregations," which had a preacher of its own in 1892-1912 in the person of C. P. van Eeghen, Jr. The "leftists" and "rightists" both were able to find a place in the body of the brotherhood, and both bore with one another in a brotherly way. They seldom even learned to appreciate each other.

The Activities in the District Conferences and Groups

It has been noted that at the beginning of this period the Mennonites were suffering heavy losses in membership. About 1830 the trend was halted. By 1855 a growth was reported, and although in the following years a number of Mennonites joined a schismatic Reformed group (known as the Doleerenden, i.e., "Troubled Ones") especially in the countryside in Groningen and Friesland, a growth in membership continued which was partly due to transfers from the Reformed Church of those who could not stand the increasingly (since 1875) confessional character of that church. Hence the period of 1880 to 1900 was characterized by growth.

Much credit was due to the ADS for the manner in which it helped the brotherhood, both in the training of preachers and in strong financial support of the weak congregations. Various other organizations also made their contributions. The Mennonite conference in Friesland (Friesche Doopsgezinde Sociëteit) was still active. In 1826 a new conference (Sociëteit) was organized in Groningen, which also included the congregations of East Friesland in Germany. In North Holland the old Rijper Sociëteit continued its good work on behalf of the congregations. In 1840 the congregations in Overijssel, Gelderland, and Utrecht formed an association, which was joined in 1858 by the congregations in South Holland and Zeeland, and which in 1885 called itself the Zwolsche Vereniging.

In the 19th century a number of district organizations, called Rings, were established for the purpose of helping to maintain a good supply of preaching, particularly when a pulpit was vacant or the preacher ill. Each Ring served about 10-15 congregations. The oldest is Ring Akkrum (1837), followed by Ring Bolsward (1840), Ring North Holland with two chapters (1844), Ring Dantumawoude (1850), Ring Twenthe (1856), Ring Arnhem (1856), Ring Zwolle (18--), Ring South Holland-Zeeland (18--), and finally in the 20th century, split off from Ring Arnhem, Ring Utrecht-het Gooi (1947). The Groningen Sociëteit also acts as a Ring.

In 1861 the Haarlem Vereniging of Mennonite congregations was founded, which among other things furnished certifications and looked after scattered members living outside the regular congregations. From 1896 on visiting preachers were provided to minister to Mennonites living where there were no congregations. The Haarlem Association continued until 1925.

In 1794 the congregations in North Holland and in 1804 those in Friesland established a Fonds (foundation) for the support of the widows of Mennonite preachers, and in 1810 a similar fund, the Zwolsche Fonds, was established, which merged with the older North Holland Foundation in 1897. In 1835 the Groningen Sociëteit had also established a foundation for widows. At the same time foundations were established to pay pensions to retired and invalid ministers, such as the Zaansche Fonds (1848; see Algemeen Emeritaatsfonds), the Friesche Emeritaatsfonds, and the Groningen Fonds (1917). In 1929 the ADS established a foundation for the increase of pensions. In 1865 the Foundation for the Increase of Salaries was established, and in 1917 the Menno Foundation was established for the same purpose, while in 1912 the Dienstjaren Fonds accomplished the same purpose by granting supplementary payments to preachers who had served ten years or more and had low salaries. The ADS established a general Pensioenfonds in 1946.

New Congregations

Between 1811 and 1957, 30 new congregations arose, some of them at places where there had been a Mennonite congregation in earlier times. The 25 were Mensingeweer 1816, Tjalleberd 1817, Beverwijk ca. 1825, Stadskanaal 1848, Pekela 1852, Arnhem 1852, Wolvega 1861, Koudum 1867, St. Anna-Parochie 1871, Huizen-Hilversum 1878, Meppel 1879, The Hague 1881, Apeldoorn 1896, Assen (as Kring or circle 1896, as a congregation 1898), Breda 1896, Dordrecht 1896, Wageningen 1896, Zwaagwesteinde (Kring 1904, congregation 1942), Amersfoort (Kring 1905, congregation 1923), IJmuiden 1909, Bussum (Kring 1909, congregation 1915), Baarn (Kring 1909, congregation 1921), Delft (Kring 1918, congregation 1923), South Limburg (Kring 1924, congregation 1931), Eindhoven (Kring 1929, congregation 1936), Zeist (Kring 1929, congregation 1931), Haarlemmermeer 1950, North East Polder 1953, Roden 1954, Emmen 1957, Buitenpost 1957.

In 1957 there were in the Netherlands 136 congregations, of which, however, a considerable number had joined with other neighboring congregations in a pastoral circuit with one common pastor. In addition there were 24 circles (Kring). The total baptized membership was 38,446. Detailed statistics of membership appear at the end of the article. In January 1957, 16 congregations had no pastors, but there were a total of 109 pastors serving in congregations, besides three in general work. Of the 112 preachers 25 were women. In most of the congregations new meetinghouses and parsonages had been built since 1811. Four meetinghouses, completely destroyed during World War II, i.e., at Rotterdam, Wageningen, Vlissingen, and Nijmegen, were rebuilt by the support of the Noodfonds, a fund established by the ADS, to which congregations and private persons liberally contributed, in addition to state aid.

Between 1811 and 1957 only two Mennonite congregations became extinct, the small one at Appelsga, which was founded at the beginning of the 19th century, and Maastricht. The property of the Maastricht congregation, which became extinct in 1815, was taken over by the state.

The Dordrecht congregation also died out and lost its capital, but a new congregation arose in 1879. In 1853 most of the Old Frisian congregation at Balk, which had stood quite alone in maintaining its old customs and insisting on the wearing of outmoded clothing, immigrated to North America, settling near Goshen, IN. A chief reason for the emigration was that it was no longer possible to secure exemption of the young men from military service.

A number of congregations which were located side by side in the same town merged during this period; e.g., Joure in 1816, IJlst 1817, Grouw 1827, Sneek 1838, Ameland 1855, Aalsmeer 1866, Oldeboorn 1886, Wormerveer 1899, Westzaan 1930, and Zaandam 1949. The Swiss congregations at Kampen (1822) and at Groningen (1824) also joined older Dutch congregations.

Congregational Life

The inner life of the brotherhood has also experienced changes. In the 1870's much attention was given to the question of baptism, and a number of articles on the subject appeared in the Doopsgezinde Bijdragen. As has been noted above, members of other denominations who had been baptized as infants could be admitted into the church at Zwolle and elsewhere in 1808 without baptism upon confession of faith. Although this was not universally approved it came to be a permanent practice in the brotherhood. In a meeting of the Ring South Holland-Zeeland in 1864 the general opinion was that such candidates should be rebaptized. But in 1871 the Midwolda congregation in Groningen decided that one could become a church member without being baptized. The congregation at Vlissingen actually voted to accept transfer members without baptism, action which stirred up trouble. In 1879 a conference was held in Amsterdam under the leadership of Jacobus Craandijk, pastor of Rotterdam, to discuss this matter. Here Jeronimo de Vries, pastor at Haarlem, proposed that baptism be made optional, and added that he had no objection to its complete elimination. On the opposite side were the Amsterdam leaders (Pastor T. Kuiper, H. S. van Eeghen, F. Muller, and others), who insisted that there must be adult baptism on confession of faith: "It is Christ's command." No agreement was reached.

In many congregations it became a custom to accept members of other creeds without adult baptism, which by 1957 was the general practice. Personal choice as to baptism or no baptism in admission to the church, as had been practiced at Midwolda, did not appeal to the churches, even though now and then an individual was admitted without baptism.

The Lord's Supper, although especially in Friesland it still enjoyed a warm participation which is shown in faithful attendance, was no longer the heart of the congregational life as it formerly was, although in the mid-20th century a change to a higher evaluation was noticeable. In Winterswijk, after it had not been observed for several years, the Lord's Supper was observed again after 1910. In Franeker it was abandoned in 1915, but observed again regularly since 1934. The Lord's Supper was usually observed once a year; in some congregations the members were seated around the table, in others they remained at their places while the pastor(s) and deacons handed them the bread and wine. In Amsterdam both methods were used.

By 1957 congregational singing in all the congregations was accompanied by an organ. About 1910 the last congregation decided to install one. After 1811 the content of the songbooks also changed somewhat. Amsterdam introduced Christelijke Gezangen (2 volumes) in 1848, in 1849 Rotterdam adopted the Remonstrant hymnal in a revised form. In 1851 Haarlem adopted a new hymnal, Christelijke Kerkgezangen. Amsterdam introduced its two new hymnals, Christelijke Liederen, in 1870. All these hymnals were also adopted in other places. In 1882 the Dutch Protestant Union compiled a hymnal, in 1920 a continuation of this hymnal appeared, which was also adopted in many Mennonite churches, first in Texel (1885). Haarlem received new hymnals once more in 1895 in two books, of which the first was a selection of Mennonite hymns, and the second the Protestant Lutheran one with some changes. In 1897 the ministers J. Sepp and H. Boetje issued the Leidsche Bundel, which was widely used. In 1900 it was followed by a selection from the Psalms. Thus there were still in the congregations ten or more different hymnbooks in use. This diversity in hymnals remained until after World War II, when the new Doopsgezinde Bundel was introduced, which was used in all but one or two congregations.

In 1911 at Bovenknijpe Miss Anna Zernike, the first woman preacher in the brotherhood, delivered her initial sermon (see Mankes-Zernike, Anna); the meeting of the ADS of 1905 had made this possible. Women also were made members of the church councils, the first ones shortly after 1900. By the mid-20th century nearly all the congregations had women on their church boards.

Since the beginning of the 20th century the usual worship service has no longer been the sole form of congregational life. Lectures and "devotional hours" were held. In addition Sunday schools and youth work, choirs, and sewing societies were founded everywhere, and later sisters' associations and occasionally also brothers' associations, while also youth associations were found nearly everywhere.

The relationship to the state has remained as it was regulated in 1796. The church is separated from the state. There is no longer any privilege granted to members of a particular church. By means of this equalization it became possible for Mennonites to occupy a relatively high percentage of state offices, even the highest. When the law of 1815 and again that of 1817 offered the Mennonites the use of some funds as state contributions for the pastors' pay for many congregations and a children's supplementary grant for the preachers, at first a few could not make up their mind to accept them. An important sum was actually raised for this support to prevent the acceptance of state funds, but gradually the doubt disappeared, and now the supplementary "Rijkstraktement" and "Kindergelden" are generally accepted. By the law of 10 September 1853 each congregation is a church unit and has the legal rights of a person. When the government wanted to reach the Mennonites as a whole it addressed itself to the ADS. In 1898 once more the old Mennonite privilege of release from military service was discussed. In that year a law was passed making it a personal obligation to serve, which did away with the hiring of a substitute which had been valid since 1799. This older regulation, according to which any one who had to become a soldier could employ a substitute, was often made use of by the Mennonites. No opposition to this new ruling came from the church. But there were difficulties. This was shown in World War I. Finally the law of alternative service was formulated (1925) in favor of the Mennonites and other antimilitary groups, giving those who had conscientious scruples the opportunity of service in a number of nonmilitary state tasks.